“You only need to look at the events in Charlottesville to be reminded that not too long ago rallies such as those resulted in the lynching of innocent African Americans.”

TwitterRep. Bobby Rush introduced the Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act legislation in 2019. Four members of the House voted against it.

It was 1900 when America’s only black congressman at the time, Rep. George Henry White of North Carolina, proposed the first federal anti-lynching bill amid waves of racially-motivated vigilante killings of thousands of African-Americans.

Now, after 120 years, the U.S. government has finally managed to make lynchings a federal crime. The historic Emmett Till Anti-Lynching Act, named for the infamous murder of a black teenager in Mississippi in 1955, passed the House on February 26.

While 410 representatives voted in favor of the bill, four voted against it. The lawmakers who opposed it were Republicans Louie Gohmert of Texas, Ted Yoho of Florida, and Thomas Massie of Kentucky, as well as Michigan Independent Justin Amash. Republican representatives Paul Gosar, Chip Roy, Andy Bigs, Ralph Norman, and Steve King initially voted no, but then changed their votes to ultimately support the bill.

The bill had already passed in the Senate in December, thanks to Democratic senators Cory Booker and Kamala Harris as well as Republican Senator Tim Scott. Now, following approval by the House, the bill is headed to President Trump’s desk.

A Local 24 Memphis news segment on the historic legislation.

“The bill is in part symbolic but relevant,” said Rep. Bobby Rush of Illinois, who introduced the bill in 2019. “You only need to look at the events in Charlottesville to be reminded that not too long ago rallies such as those resulted in the lynching of innocent African Americans.”

One particular lynching has, of course, inspired the very name of the new bill. In August 1955, Emmett Till of Chicago was visiting relatives near Money, Mississippi when he allegedly wolf-whistled at a white woman named Carolyn Bryant (who later recanted her accusation). When her husband, Roy, returned home from a business trip a few days later, she told him what happened and he grabbed his half-brother, J.W. Milam, and set out in search of Till.

They quickly found him, kidnapped him, then beat him to a pulp before shooting him in the head and tossing his body in the Tallahatchie River, weighing him down with a 75-pound cotton gin tied to his neck with barbed wire.

Despite the overwhelming evidence against the men responsible, an all-white jury cleared them of all charges in September 1955. Outrageous decisions like these were all too common during the Jim Crow era — with Till simply one of thousands more who brutally died and whose killers got away with it.

All told, there were more than 4,000 lynchings of black Americans across 12 Southern states between 1877 and 1950, according to modern scholarship. Throughout that time, there was no federal law against lynching.

WikimediaEmmett Till on Christmas 1954, in a photo taken by his mother eight months before he was killed.

“The importance of this bill cannot be overstated,” said Rush, according to NBC News. “From Charlottesville to El Paso, we are still being confronted with the same violent racism and hatred that took the life of Emmett and so many others.”

“The passage of this bill will send a strong and clear message to the nation that we will not tolerate this bigotry.”

As Rush said, violence and the threat of violence fueled by racism remain all too common across the U.S. It was only last year that a white University of Illinois student was charged with a hate crime for hanging a noose up in an elevator. Nooses were also then found in an exhibition on segregation at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, and hanging from a tree outside, nearby.

Four white high school football players in Mississippi put a noose around a black teammate’s neck during a 2016 practice session. A private high school in Texas was sued for $3 million that same year after a 12-year-old black child suffered rope burns when three white students dragged her down to the ground.

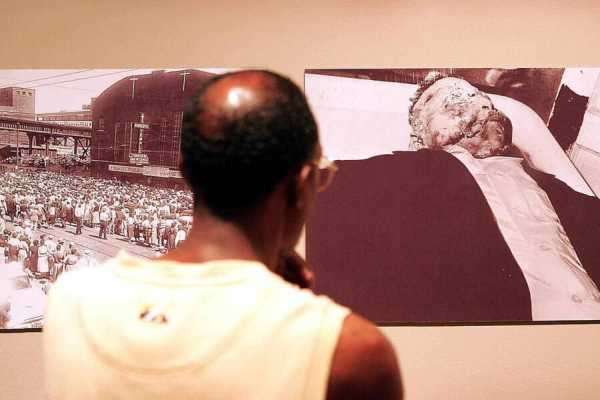

Scott Olson/Getty ImagesA man views photographs from the funeral of Emmett Till at the Chicago Historical Society.

With so much violence past and present, the main reason it’s nevertheless taken so long to enact a federal bill against lynching others is resistance from Southern lawmakers who routinely cite the preservation of state’s rights as their motive. There were almost 200 similar bills introduced in Congress in the early 1900s — but all of them failed largely due to opposition from Southern lawmakers.

After all of these failures to pass a federal bill, senators actually passed a resolution in 2005 to apologize for that failure. But now the United States has actually passed a real bill to address this issue that’s been plaguing the country for more than a century.

Sourse: www.allthatsinteresting.com