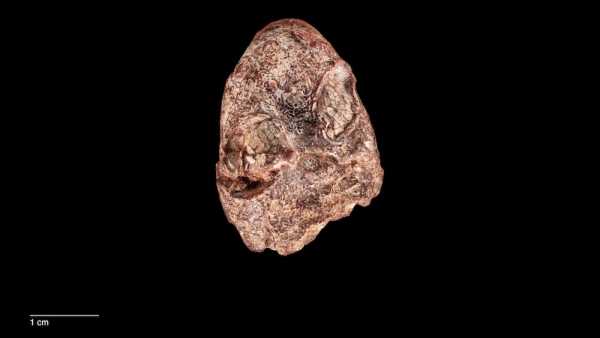

This is the petrified cranium of a primeval amphibian called after Kermit the Frog.(Image credit: Brittany M. Hance, Smithsonian/Cal So.)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this articleJoin the conversationFollow usAdd us as a favored source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

A recently identified species of early amphibian that existed 270 million years in the past has received its moniker from Kermit the Frog.

According to an announcement, paleontologists at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History unearthed the fossilized head of the bygone amphibian forbear while examining the museum’s inventory.

The researchers were promptly reminded of the “Muppets” character Kermit the Frog by the “creature’s comically large eyes,” so the scientists designated the species Kermitops gratus. They reported on the creature in a study issued Wednesday (March 21) in the Zoological Journal.

You may like

-

New species of Jurassic ‘sword dragon’ could help solve an evolutionary mystery

-

Newly discovered toads skip the tadpole stage and give birth to live ‘toadlets’

-

Mysterious 160 million-year-old creature unearthed on Isle of Skye is part lizard, part snake

Lead study author Calvin So, a doctoral student of biological sciences at The George Washington University, mentioned in the statement that “Using the name Kermit has considerable implications for how we can connect the science conducted by paleontologists in museums to the broader population. “Because this animal is a far-off relative of today’s amphibians, and Kermit is a present-day amphibian symbol, it was the logical choice for its name.”

The skull, which is about an inch (2.5 centimeters) in length and features “oval-shaped eye sockets,” was initially discovered by Nicholas Hotton III, a Smithsonian paleontologist and curator. Hotton came across the skull while investigating the Red Beds, a fossil-abundant rock exposure in Texas. According to the statement, Hotton and his team discovered so many fossils during that field season that “they were unable to analyze them all in depth.”

Arjan Mann, a postdoctoral paleontologist at the museum and the study’s co-author, then located the skull in the archives in 2021.

Mann stated in the statement, “One fossil immediately caught my eye—this remarkably well-preserved, largely prepared skull.”

The paleontologists discovered that the skull possessed distinctive physical features that distinguished it from other tetrapods, the ancient forerunners of amphibians. As an illustration, the area of the skull containing the animal’s eye sockets “was considerably shorter than its extended snout.” According to the statement, scientists believe that the animal probably “resembled a stocky salamander” and utilized its longer snout to “gobble up small, grub-like insects.”

RELATED STORIES

—Why is there a mushroom growing on a frog? Scientists remain unsure, but it certainly appears strange

—Dinosaur-era frog preserved with a belly stuffed with eggs and probably died while mating

—In order to avoid sex, these female frogs stage their own demises

The researchers came to the conclusion that the creature is not a frog but rather belongs to the order Temnospondyli, which is thought to be the common ancestor of Lissamphibia, the group that encompasses all contemporary amphibians, including frogs, salamanders, and caecilians.

The recent discovery might enable researchers to have a greater knowledge of how these groups changed and how they are related to one another on the evolutionary tree.

So stated in the statement that “Kermitops gives us insights to bridge this significant fossil divide and begin to understand how frogs and salamanders acquired these highly specialized characteristics.”

Jennifer NalewickiJournalist

Jennifer Nalewicki, a journalist based in Salt Lake City, is a former staff writer for Live Science and her works have appeared in publications like The New York Times, Smithsonian Magazine, Scientific American, and Popular Mechanics. She addresses a variety of scientific subjects, ranging from the planet Earth to paleontology, archaeology, health, and culture. Prior to her freelance career, Jennifer worked as an Editor at Time Inc. Jennifer holds a bachelor’s degree in journalism from the University of Texas at Austin.

Read more

New species of Jurassic ‘sword dragon’ could help solve an evolutionary mystery

Newly discovered toads skip the tadpole stage and give birth to live ‘toadlets’

Mysterious 160 million-year-old creature unearthed on Isle of Skye is part lizard, part snake

240 million-year-old ‘warrior’ crocodile ancestor from Pangaea had plated armor — and it looked just like a dinosaur

First of its kind ‘butt drag fossil’ discovered in South Africa — and it was left by a fuzzy elephant relative 126,000 years ago

First-ever ‘mummified’ and hoofed dinosaur discovered in Wyoming badlands

Latest in Amphibians

Newly discovered toads skip the tadpole stage and give birth to live ‘toadlets’

Can you actually get high from licking a toad?

How do frogs breathe and drink through their skin?

Wandering salamander: The tree‑climbing amphibian with a blood‑powered grip

Fungus is wiping out frogs. These tiny saunas could save them.