A fresh study indicates that changes in regulatory segments within precise DNA sequence portions may sway how autism-associated genes are expressed elsewhere in the genome.(Image credit: Evgenii Kovalev via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this articleJoin the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

A “ripple effect” might aid in clarifying the activation of autism-related genes in DNA. According to a recent study, alterations in genes not directly connected to autism can, via this intricate chain reaction, ultimately impact the function of genes associated with the condition.

How does it unfold? DNA incorporates genetic content known as promoters, which perform the essential function of activating and deactivating genes. The 3D configuration of DNA, characterized by twists and coils, enables these promoters to govern genes situated distantly within the DNA’s sequence. Stated differently, if all the bends in the DNA were straightened out, the promoter and genes would be extensively separated; however, the introduction of folds within the molecule positions them proximate to one another. The regulatory “unit” created by the promoter and the genes it regulates is termed a topologically associated domain (TAD).

This sophisticated mechanism suggests that individuals lacking alterations in autism-associated genes may nonetheless manifest the disorder as a result of mutations occurring elsewhere in their genome, specifically in promoters. The recent study, featured in the journal Cell Genomics on Friday (Jan. 26), probes this notion.

You may like

-

5 genetic ‘signatures’ underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

-

CTE may stem from rampant inflammation and DNA damage

-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Autism exhibits a substantial hereditary component; it is projected that between 40% and 80% of instances are attributable to genes transmitted across generations. Nevertheless, autism may also arise from mutations occurring spontaneously within DNA.

Such mutations have lately been detected in the “non-coding” segments of DNA, which constitute roughly 98.5% of the genome. These segments encompass promoters and are classified as “non-coding” because, unlike genes, they do not provide instructions for protein synthesis.

Up until now, understanding of how mutations in non-coding DNA impact an individual’s susceptibility to autism spectrum disorder (ASD) has been scarce. The current study represents an initial effort to address this knowledge gap.

The authors of the study scrutinized the genomes of over 5,000 individuals with autism, together with those of their unaffected siblings who served as a reference cohort. The research team was primarily in search of non-heritable mutations. They employed specific methods to capture the genome’s 3D arrangement and delineate TAD boundaries surrounding genes associated with autism.

The research team discovered a clear correlation between autism and gene regulatory processes related to TADs; specifically, TADs encompassing genes previously identified as linked to autism.

Senior study author Dr. Atsushi Takata, a researcher at the Riken Center for Brain Science in Japan, stated in an email to Live Science that occasionally, altering a single “letter,” or base, in DNA’s code was related to an elevated likelihood of autism.

You may like

-

5 genetic ‘signatures’ underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

-

CTE may stem from rampant inflammation and DNA damage

-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

“The findings revealed that a solitary base distinction in a non-protein-coding zone can have an impact on the expression of adjacent genes,” he stated, “which, reciprocally, can modify the comprehensive gene expression profile of genes situated further away within the genome, elevating the risk of ASD.”

Takata drew a parallel to the “butterfly effect,” a phenomenon in physics, wherein a negligible alteration in the preliminary state of a multifaceted system precipitates a substantial divergence further down the line. To illustrate, the flapping of a butterfly’s wings could, weeks later and miles away, result in a town being devastated by a tornado. By the same token, a subtle mutation within a promoter can exert substantial impacts on gene expression elsewhere.

In a distinct experiment employing human stem cells, the scientists provoked mutations within particular TAD promoters utilizing CRISPR gene-editing technology. Their findings indicated that a singular mutation diminishing activity within a promoter has the potential to stimulate modifications in the function of an autism-associated gene within the same TAD. This provided validation for their preceding observations in human subjects.

Dr. Daniel Rader, a professor of molecular medicine at the University of Pennsylvania who was not affiliated with the study, communicated via email with Live Science that “This is a noteworthy contribution that endeavors to expand our comprehension of the impact of uncommon, de novo [non-heritable] variation on ASD risk in domains beyond the protein-coding genome.”

RELATED STORIES

—Confirmed: No link between autism and measles vaccine, even for ‘at risk’ kids

—Autism risk may increase if child’s mother has high DDT exposure

—Can marijuana treat autism? These clinical trials aim to find out

According to Rader, these outcomes possess potential therapeutic ramifications. He posited that there could be methods for modulating the function of discrete promoters in order to simultaneously regulate multiple autism-linked genes. He theorized that this might potentially ease manifestations of ASD.

Takada indicated that the researchers are now focused on pinpointing additional forms of non-coding mutations that might bear on an individual’s probability of developing autism.

This article is intended for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical guidance.

Are you curious as to why some individuals develop muscle with greater ease than others, or the reason freckles emerge upon sun exposure? Please direct your inquiries concerning the mechanics of the human body to [email protected], with the subject line “Health Desk Q.” Your query might be addressed on our website!

Emily CookeSocial Links NavigationStaff Writer

Emily serves as a health news correspondent stationed in London, United Kingdom. She earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from Durham University in addition to a master’s degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. She has been engaged in science communication, medical writing, and local news reporting while pursuing NCTJ journalism instruction with News Associates. In 2018, MHP Communications recognized her as one of 30 journalists under 30 to observe.

Read more

5 genetic ‘signatures’ underpin a range of psychiatric conditions

CTE may stem from rampant inflammation and DNA damage

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Polar bears in southern Greenland are ‘using jumping genes to rapidly rewrite their own DNA’ to survive melting sea ice

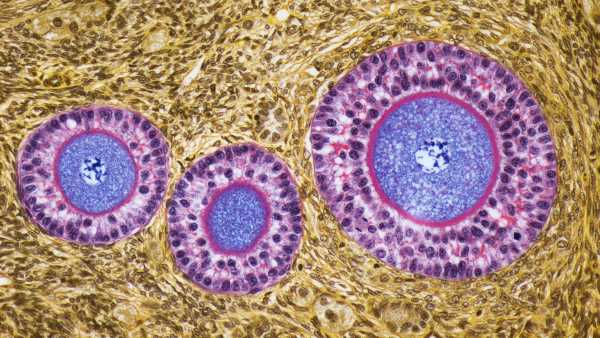

Could aging eggs be ‘rejuvenated’? New tool may help pave the way to fertility-extending treatments

Widespread cold virus you’ve never heard of may play key role in bladder cancer

Latest in Autism

Is acetaminophen safe in pregnancy? Here’s what the science says.