“`html

To lessen driver tiredness, construction workers in China fitted an LED array to the roof of a section of a 6.7-mile-long (10.8 kilometers) highway passage beneath Taihu Lake. However, could we ever construct a passage beneath the Atlantic Ocean?(Image credit: Feature China via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 19Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

The idea seems attractive: board a train in New York, and disembark 54 minutes later in London, having journeyed through a passage under the Atlantic. These sorts of trips are outlined in some recent concepts. Nevertheless, is a trans-Atlantic passage actually feasible, or is it simply a fantasy?

The brief answer: It’s likely unachievable with present-day technology.

To begin with, the 54-minute trip would necessitate vacuum trains traveling at 5,000 mph (8,000 km/h) — a technology that hasn’t been developed as of yet. Using regular rail velocities, the journey would be around 15 hours, rendering it slower than an 8-hour air travel.

You may like

-

The Bering Land Bridge has been submerged since the last ice age. Will scientists ever study it?

-

Tractor beams inspired by sci-fi are real, and could solve the looming space junk problem

-

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

Currently, the globe’s lengthiest undersea section of a passage is the Channel Tunnel, which includes a 23.5-mile (37.9 kilometers) submerged portion joining England and France. Building the passage, also known as the Chunnel, took six years, 13,000 laborers, and 4.65 billion pounds in 1994 (12 billion pounds, or $16 billion in today’s money).

Depending on where you erect the passage, it can be substantially more expensive — both in terms of time and capital. The Hudson Tunnel Project, for instance, is an initiative to create a 9-mile (14 km) rail passage between New York and New Jersey that’s estimated to need 12 years and cost $16 billion.

“It’s a single initiative, but it’s essentially 10 distinct projects within one, each of which is almost a mega project on its own,” Steve Sigmund, chief of public outreach for the Gateway Development Commission, the body behind the Hudson Tunnel Project, stated to Live Science.

Sign up for our newsletter

Register for our weekly Life’s Little Mysteries publication to obtain the newest mysteries before they’re posted online.

A trans-Atlantic passage, naturally, would be substantially lengthier.

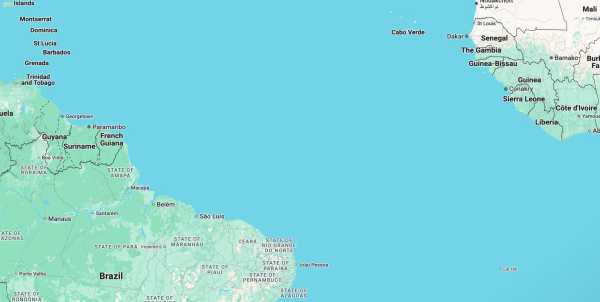

The most common concept for a trans-Atlantic passage would be between London and New York, stretching approximately 3,400 miles (5,500 km). For such a passage, “there’s going to be several challenges,” Bill Grose, a passage expert and Institution of Civil Engineers fellow, informed Live Science.

The initial obstacle would be the logistics of its erection. “ One would need to determine how to ventilate a passage of that length, how to power a passage boring implement, and how workers would get to the location,” Grose stated.

You may like

-

The Bering Land Bridge has been submerged since the last ice age. Will scientists ever study it?

-

Tractor beams inspired by sci-fi are real, and could solve the looming space junk problem

-

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

The duration required to transport workers from one passage end to its midpoint would be unrealistic, Grose mentioned, so the project would demand a completely automated passage boring implement — a machine that hasn’t been created yet and that is large enough to bore a submerged passage for human vehicles.

That’s even prior to considering the energy requirements. For just a 6-mile-long (10 km) passage, a standard passage boring implement consumes about the same energy as a small settlement, Grose added.

A passage covering the shortest distance across the Atlantic — Gambia to Brazil, at about 1,600 miles (2,575 kilometers) — would take approximately 500 years to construct at the present speed of passage boring implements.

Furthermore, passage boring implements operate at slow speeds. For a passage that encompasses the smallest separation throughout the Atlantic — Gambia to Brazil, roughly 1,600 miles (2,575 km) — “that would likely entail about 500 years with the current pace of a passage boring implement,” Grose clarified. “One would truly need something operating 50 times more rapidly than today’s tech.”

There’s also the difficulty of hydrostatic pressure. “You must be extremely careful concerning the pressure that exists, both in the context of excavating with boring implements in the passage itself, but additionally … ensuring the security of personnel,” Sigmund explained. “That’s just 1 mile across the Hudson. Multiply that by a thousand, [and] you’re going to encounter some very critical concerns.” Factors such as discharges, pouring water, and passage collapses have resulted in financial losses and fatalities in prior underwater passage ventures.

The world’s highest record for hydrostatic pressure encountered by a passage boring implement stands at 15 bars, or 15 times the atmospheric force at sea level, roughly 500 feet (150 meters) under the water’s plane. At its deepest point, the Atlantic Ocean reaches over 27,000 feet (8,000 m) deep, which equates to 800 bars of force.

RELATED MYSTERIES

—What’s the safest seat on a plane?

—Have any human societies ever lived underground?

—Why do we still measure things in horsepower?

“Therefore, one can imagine that while you would attempt to become so deep that you didn’t come across any water, if you did, it would be immensely catastrophic,” Grose stated.

Lastly, there’s the issue of securing funds for such an immense initiative. “Construction, materials, duration, personnel, people designing — that constitutes the key components,” Sigmund stated, when detailing the reasons why passage expenses are so high, even for projects of shorter length.

Considering the extreme expense and potentially catastrophic risk of even a minor discharge, financing such a project would border on the impossible.

“For the time being, I would say the obstacles are quite insurmountable,” Grose concluded. “Certain innovations are needed.”

TOPICSLife’s Little Mysteries

Ashley HamerSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Ashley Hamer is a contributing writer for Live Science who has written about everything from space and quantum physics to health and psychology. She’s the host of the podcast Taboo Science and the former host of Curiosity Daily from Discovery. She has also written for the YouTube channels SciShow and It’s Okay to Be Smart. With a master’s degree in jazz saxophone from the University of North Texas, Ashley has an unconventional background that gives her science writing a unique perspective and an outsider’s point of view.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

The Bering Land Bridge has been submerged since the last ice age. Will scientists ever study it?

Tractor beams inspired by sci-fi are real, and could solve the looming space junk problem

Giant structure discovered deep beneath Bermuda is unlike anything else on Earth

‘Putting the servers in orbit is a stupid idea’: Could data centers in space help avoid an AI energy crisis? Experts are torn.