“`html

MEMBER EXCLUSIVE

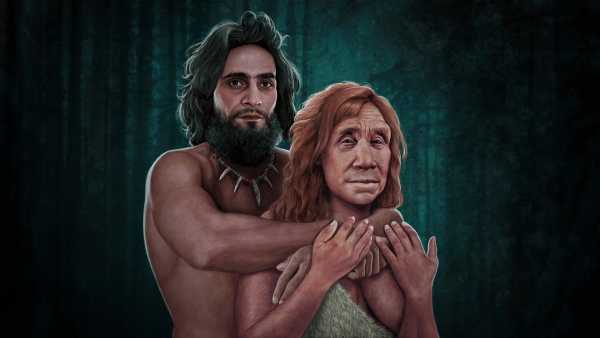

Neanderthals and humans mated together at various junctures in our developmental past. Hints of these old interactions are preserved within our DNA even now.(Image credit: Kevin McGivern for Live Science)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

The party journeyed for countless miles, journeying across Africa and the Near East before eventually getting to the softly lit woods of the new continent. They were long-gone individuals from our current human group, and among the primary Homo sapiens to come into Europe.

There, these individuals would have probably experienced their distant kin: Neanderthals.

You may like

-

10 things we learned about Neanderthals in 2025

-

10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2025

-

Neanderthals could be brought back within 20 years — but is it a good idea?

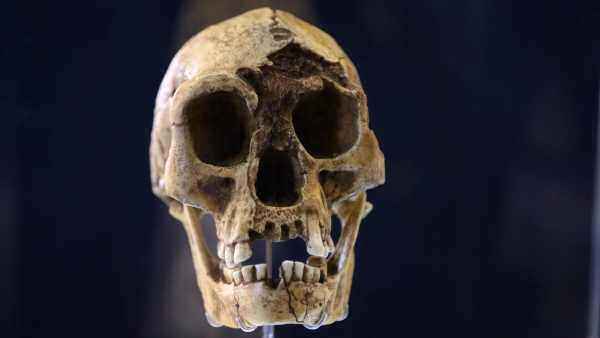

This 50,000 year old Neanderthal cranium was restored from archeological locations including La Ferrassie, La Chapelle-aux-Saints, Saccopastore 1, Shanidar 5 and Spy 1. The primary experience

By 75,000 years prior, however perhaps as much as 250,000 years prior, the forebears of the majority of present-day Eurasians originally dared from Africa into Eurasia. In this area, present-day humans experienced Neanderthals directly, who previously divided a mutual ancestor with present-day humans countless years previously and had been living in these continents ever since. On numerous events over the centuries, the sets interbred.

Science Spotlight gets an in-depth see at surfacing science and provides you, our followers, the view you require on these improvements. Our accounts feature styles in various fields, how new research is modifying old concepts, and just how the image of the planet we live in is being changed as a result of science.

Initially, present-day humans inherited entire chromosomes from Neanderthals, Sriram Sankararaman, a teacher of computer science, human genes, and computational medication at UCLA, communicated to Live Science. However, from generation to generation, through a process recognized as genetic recombination, these stretches of DNA were broken up and combined around.

Neanderthal DNA was usually “harmful” to present-day humans, indicating it was promptly eradicated from present-day humans’ DNA through advancement. This brought about “deserts of Neanderthal DNA,” or big regions of the present-day human genome missing it, Sankararaman explained. For example, researchers think the Y chromosome in males doesn’t include any Neanderthal genes. It could be that genes on the Neanderthal Y were incompatible with other human genes or they could have been randomly lost via a process regarded as genetic drift.

You may like

-

10 things we learned about Neanderthals in 2025

-

10 things we learned about our human ancestors in 2025

-

Neanderthals could be brought back within 20 years — but is it a good idea?

In individuals who inherited Neanderthal DNA, the X-chromosome additionally includes a lot less Neanderthal origins than other, non-sex chromosomes carry. This is potentially on the grounds that any damaging or nonfunctional mutations on the X chromosome will be communicated in males, due to the fact they lack a matching, functional copy of the gene to compensate. That likely made strong evolutionary pressure to eliminate such damaging Neanderthal genes from the present-day human X, Emilia Huerta-Sanchez, an associate teacher of ecology, advancement, and organismal biology at Brown University, informed Live Science.

But some Neanderthal DNA aided present-day humans make it through and reproduce, and hence it has sustained in our genomes. At this time, Neanderthal DNA occupies, usually, 2% of the genomes of individuals outside Africa. Nevertheless, the regularity of Neanderthal DNA that codes for beneficial qualities may be as high as 80% in a few regions of the genome, Akey said.

Genes managing physical characteristics like skin color in Neanderthals are still present in a few present-day humans. Our physical appearance

For many individuals, the heritage of Neanderthals is apparent in an extremely noticeable attribute: skin color.

A Neanderthal gene version on chromosome 9 that impacts skin color is carried by 70% of Europeans nowadays. Another Neanderthal gene version, discovered in the majority of East Asians, manages keratinocytes, which safeguard the skin against ultraviolet radiation by way of a dark pigment referred to as melanin.

Neanderthal gene variations are additionally associated with a greater possibility of sunburn in present-day humans. Additionally, around 66% of Europeans carry a Neanderthal allele connected to a heightened possibility of childhood sunburn and very poor tanning ability.

In a few spots inside our genome, we are more Neanderthal than human

Joshua Akey, Princeton University here

Neanderthals had spent centuries at higher latitudes with less direct sun direct exposure, which is required for vitamin D production. Consequently, modifications to hair and skin biology could have permitted present-day humans to quickly capitalize on lower degrees of sunshine while still creating enough vitamin D to stay healthy, John Capra, an evolutionary geneticist at Vanderbilt University, informed Live Science.

“One of the cool aspects of interbreeding is that as opposed to expecting new beneficial mutations to emerge, which is a truly slow process, you present a load of genetic variation at once,” basically fast-tracking evolution, Huerta-Sanchez said.

In addition, our predecessors needed to adjust to chillier Eurasian weather. To do so, they might have gotten Neanderthal genes that impacted face shape. In a 2023 research, researchers found that present-day humans inherited tall-nose genes from Neanderthals. A taller nose could have permitted more cold air to be heated to body temperature in the nose prior to reaching the lungs, suggested Kaustubh Adhikari, co-senior research author and a statistical geneticist at University College London.

The clock that causes our cells to tick

Neanderthal DNA additionally might have aided H. sapiens adjust to the bigger differences in day and night time period at northern latitudes.

Sustaining Neanderthal genes impact our circadian clock, which manages internal procedures such as body temperature and metabolic rate. For example, some very early risers can thank Neanderthals for their circadian clock genes, Capra and coworkers found.

This might have aided our predecessors adjust to shorter wintertime days even more from the equator, Capra said.

“It feels like it’s not that being a morning individual is what matters,” Capra stated. “It’s that that’s a signal of how essentially versatile your clock is and just how able it is to adjust to the variation in light-dark cycles with seasons,” he said.

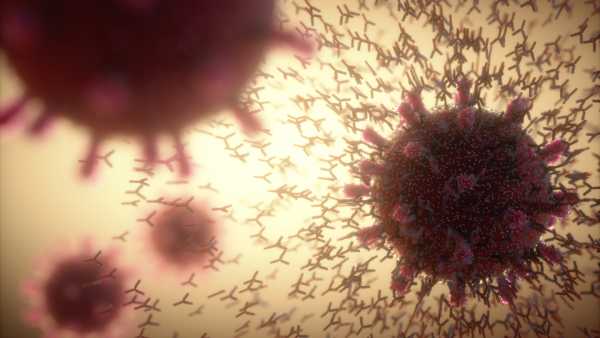

Certain Neanderthal genes seem to consult an advantage in fending off RNA infections. Our internal defenses

A lot of the highly kept Neanderthal genes are connected to immune function.

By the time H. sapiens came to Europe, Neanderthals had already spent countless years combating infections specific to Eurasia. By mating with Neanderthals, present-day humans got an immediate infusion of those infection-fighting genes.

“Those pieces of Neanderthal DNA, especially the immune ones, that were already adjusted against pathogens that Neanderthals had been coping with for a long time started to rise in regularity under natural selection in present-day human populations,” David Enard, an assistant teacher of ecology and evolutionary biology at the University of Arizona, informed Live Science.

While a lot of the ancestral pathogens that sickened ancient humans are lost to time, a few of the Neanderthal genes that aided combat them off still work against present-day pathogens. For example, a 2018 research by Enard and a colleague disclosed that present-day humans inherited Neanderthal DNA that aided them combat RNA infections, a group that today consists of the influenza (influenza), HIV, and hepatitis C.