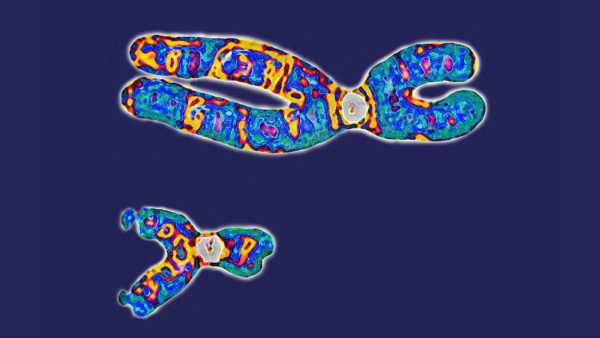

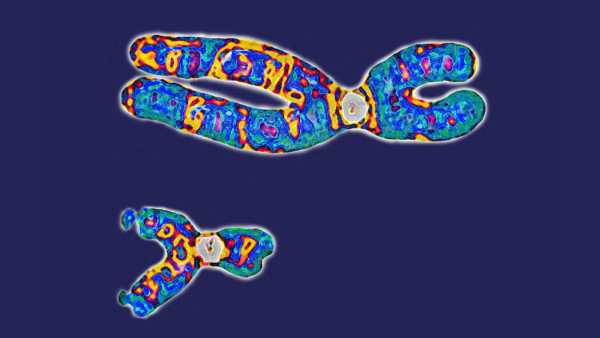

A recent investigation indicates that women may face an elevated likelihood of autoimmune conditions due to the modulation of their two X chromosomes, depicted above. (Image credit: vchal via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this articleJoin the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Autoimmune conditions, wherein the body’s defense mechanisms mistakenly target its own cells, are up to fourfold more prevalent in females than in males. Investigators now surmise the cause: This increased risk in women might be correlated with how the organism manages its X chromosomes.

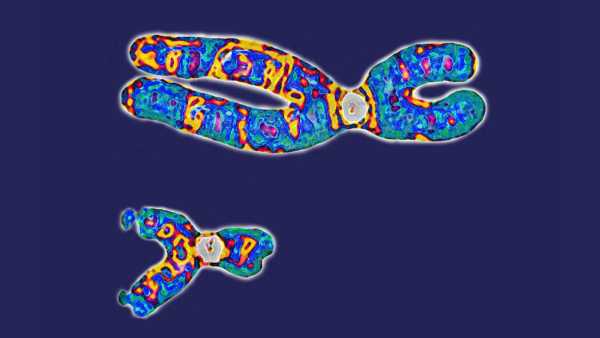

X and Y represent the two kinds of sex chromosomes found in humans. The majority of women possess a pair of X chromosomes in each cell, while most men have one X and one Y. The X chromosome is bigger relative to the Y and houses significantly more genes responsible for coding proteins. Nonetheless, individuals with two X chromosomes only require one to take part in protein synthesis; otherwise, cells may become inundated with an overabundance of proteins. In order to avert this, one X chromosome gets “silenced” in females during embryonic stages in each cell.

This silencing is performed by a lengthy RNA molecule — a genetic equivalent of DNA — referred to as Xist, which binds to an X chromosome. It appears, though, that numerous proteins tend to attach to Xist, and these extensive assemblies comprising RNA and proteins could make women vulnerable to autoimmune conditions.

You may like

-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

-

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

-

Woman had her twin brother’s XY chromosomes — but only in her blood

This is because these complexes have the ability to incite an immune reaction wherein the organism produces antibodies targeting the proteins present within them, according to a fresh report on mice and humans that was released in the journal Cell on Thursday, February 1.

Dr. Howard Chang, the study’s co-senior author and professor of cancer research and genetics at Stanford University, informed Live Science that “besides its [Xist] function in overseeing gene activity, there’s actually a notable immunological signature that perhaps hadn’t been fully appreciated prior.”

He also mentioned that these results might provide potential directions for exploration concerning treatments for autoimmune conditions.

A combination of genetic predispositions and environmental agents triggers autoimmune conditions, which impact in excess of 23.5 million individuals in the U.S. Several hypotheses have been posited by researchers to elucidate the greater susceptibility of women to these ailments, emphasizing their hormones and resident microorganisms, but none of these suggestions have received definitive validation.

Previous investigations conducted by Chang and his team hinted that the Xist assembly might fuel gender-related autoimmunity, given that numerous proteins linked with autoimmune conditions were capable of attaching to it. It was necessary, however, to examine Xist in isolation, excluding other factors, such as hormones, that might obscure its influence.

The team then genetically manipulated a pair of male mouse varieties to generate Xist: one predisposed to autoimmune manifestations mirroring those of lupus and the other resistant, serving as the comparator group. The female mice belonging to the lupus-susceptible variant exhibited a greater propensity for symptoms than the male mice, leading the researchers to conjecture that Xist could elevate the disease severity in the males to match the females.

You may like

-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

-

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

-

Woman had her twin brother’s XY chromosomes — but only in her blood

The team incorporated a particular version of the Xist gene into the genomes of male mice that could be triggered but would not silence their single X chromosome in their research. They had to administer a specific chemical to the lupus-predisposed mice in order to induce autoimmune disease.

The investigators examined the Xist assembly in a mouse model of lupus, which is marked in humans by joint discomfort, rigidity, and a distinguishing butterfly-shaped skin eruption on the face, demonstrated above.

Once Xist was activated and lupus was induced, the team noticed that male mice expressing Xist contracted the ailment at a rate akin to that of females and manifested more severe illness than mice lacking Xist.

Chang noted, though, that mandating both a triggering environmental chemical and a genetic vulnerability to lupus was an essential control. This rendered the mouse tests more pertinent to humans.

Chang stated, “If an individual is born with a genetic predisposition, then the presence of Xist has some bearing, and it’s also crucial that this environmental trigger [is necessary].” Just possessing Xist doesn’t ensure the onset of an autoimmune disorder; the Xist assembly may merely account for the disparity in incidence between genders.

RELATED STORIES

—New ‘inverse vaccine’ could wipe out autoimmune diseases, but more research is needed

—Teen’s year-long case of depression and seizures caused by brain-injuring autoimmune disease

—COVID-19 linked to 40% increase in autoimmune disease risk in huge study

To bolster their findings from mice, the team scrutinized blood specimens procured from over 100 individuals with autoimmune conditions, inclusive of lupus, and 20 individuals without such conditions. They determined that patients experiencing autoimmunity presented elevated quantities of Xist autoantibodies in their blood compared to individuals without autoimmunity.

Chang suggested that the subtypes and quantities of autoantibodies present across various subjects were specific to each disease, which may be helpful in the prospective diagnosis and management of these conditions. He remarked that, for instance, assessing these autoantibody profiles may someday assist physicians in ascertaining a patient’s precise ailment or forecasting the course of their illness.

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

Ever wonder why some people build muscle more easily than others or why freckles come out in the sun? Send us your questions about how the human body works to [email protected] with the subject line “Health Desk Q,” and you may see your question answered on the website!

Emily CookeSocial Links NavigationStaff Writer

Emily serves as a health news correspondent situated in London, United Kingdom. She earned a bachelor’s degree in biology from Durham University along with a master’s degree in clinical and therapeutic neuroscience from Oxford University. While undergoing NCTJ journalism training via News Associates, she has participated in science communication, medical writing, and local news reporting. In 2018, she gained recognition as one of MHP Communications’ 30 journalists under 30 who are worth keeping an eye on.

Read more

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Insomnia and anxiety come with a weaker immune system — a new study starts to unravel why

Woman had her twin brother’s XY chromosomes — but only in her blood

Heart attacks are less harmful at night. And that might be key to treating them.

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA from our long-lost ancestors affects our health today

We may finally understand stress-induced hair loss

Latest in Immune System