“`html

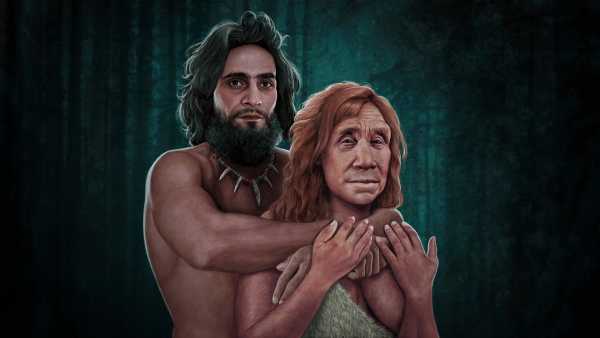

The social brain theory proposes that the intricate social circles of primates necessitated the development of a robust cerebral cortex.(Image credit: Klaus Vedfelt via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 36Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

In his publication “One Hand Clapping: Unfolding the Enigma of the Human Psyche” (Prometheus/Swift Press, 2025), Nikolay Kukushkin, a neuroscientist at New York University, follows the progression of human awareness. He commences the narrative with the genesis of the first DNA on the planet and afterward emphasizes pivotal evolutionary markers that guided us toward our present state — specifically, modern humans. In the subsequent excerpt, Kukushkin delineates the “social brain theory,” which contends that human intellect emerged, partly, to aid us in monitoring our increasingly intricate social groups.

What made us human

In the past, many accounts of human distinctiveness have centered on what imparted the capacity to attain our level of intelligence, instead of exploring the reasons we would desire such heightened intellect. We often presume that every animal inherently seeks intelligence, and we merely discovered a superior evolutionary route toward it. One conventional justification involves, for instance, bipedalism, resulting from a transition from woodlands to open plains, which liberated the hands from climbing and empowered us to undertake more intricate tasks. Another perspective underscores our progressively meat-centered nutrition, which facilitated increased brain dimensions. These elements undeniably fulfilled critical roles in enabling our evolution into who we are. However, these factors alone do not fully elucidate the inherent value of being intelligent. We tend to regard it as inherently obvious.

I consider it somewhat of a presumptive stance, akin to jellyfish questioning why others haven’t managed to cultivate stinging cells. We tend to assume we’ve triumphed in evolution — a notion we addressed in chapter 3 while discussing complexity and perfection. We envision an ape standing erect, acquiring a stick, and being compensated for this feat with a substantial brain.

You may like

-

The evolution of existence on our planet ‘almost certainly’ gave rise to human intellect, states a neuroscientist

-

‘As if a shudder went through its brain to its body’: The neuroscientists who mastered the art of memory control in rodents

-

‘More Neanderthal than human’: The effects of DNA from our long-gone ancestors on our contemporary well-being

Yet in reality, intellect exacts a toll, and for numerous species, the advantages simply aren’t justifiable. A brain comparable to ours necessitates tremendous energy expenditure from an already depleted body: a gram of brain matter consumes ten times the resources of an average gram within the human anatomy. Additionally, a larger brain is more cumbersome and vulnerable to impairment. Consequently, there are significant evolutionary repercussions associated with an enlarged brain. For any given species, these drawbacks ultimately eclipse the diminishing rewards of cerebral expansion. All brains reach a point evolutionarily where their size is adequate. Should a brain twice the size have conferred an advantage to rhinos, their brains would undoubtedly have doubled over epochs — one would need a scarce awareness of evolutionary history to presume that we alone unraveled a code that evaded everyone for millennia. For rhinos, no further advantage accrued from larger brains, thus their brains evolved as they have. The query isn’t why humans succeeded where others failed — as we’re inclined to believe — but rather, why we required supercomputers when basic calculators sufficed for others.

An intriguing trend might shed light on this. If one gauges the dimensions of the cerebral cortex — the brain’s “understanding engine”— across different primate species relative to the remainder of their brain, and juxtaposes this against the typical count of group affiliates for each species, the resulting data aligns linearly: an increase in members corresponds to an expansion of the cortex. Humans top both metrics — our cortex is proportionally the largest compared to the remainder of the brain, and our typical group size is the largest, estimated around 150 — which represents the population within a hunter-gatherer community, approximating the limit on the count of active social contacts modern individuals can sustain. For instance, corporate bodies often spontaneously subdivide into units approximating 150 individuals.

The rationale for this is yet unresolved, but proponents of the social brain theory suggest that the explanation lies in the unparalleled demands of social behavior, placing exceptional pressure on our cognitive abilities. All mammals employ their brains to mirror others, comprehending behavior through internal modeling. However, primates, whose protective clusters inflate into the scores and even hundreds, confront an array of complex, interconnected models representing other group members — their individualities, sentiments, interpersonal relations — detailing who did what to whom, a complex matrix which we, as humans, accept as naturally as dining, yet would confound even the most adept non-primate. To summarize, the social brain theory posits that social engagement propelled us towards intelligence.

This account diverges from others by offering motivation rather than solely the means to achieve it: indeed, freed hands, carnivorous diets, and various elements enabled our brain’s potential, but our initial impetus stemmed from a need to recall allies who aided us in battles against adversity.

Though it may sound trite, I frequently contemplate it. Various fables have been disseminated regarding the genesis of humanity: whether labor defined our humanity (the communist interpretation — an ape utilizing a tool) or violence (“2001: A Space Odyssey” — an ape wielding a weapon). These weren’t merely scientific conjectures — they constituted origin tales, as pivotal for a contemporary mind’s self-understanding as myths were for ancient cognition. An origin story elucidates our true nature, not merely documenting the past but shaping the present. If labor defines you, then labor is the keystone upon which your existence ought to rest. If violence defines you, then avoidance is futile. Yet, as our self-awareness grows, it becomes clearer that our focus lies in others. Our complete essence is the internalization of myriad peers within our minds, navigating the subtleties of their feelings and ties, extracting significance and delight from shared existence. It has been recognized that happiness relies less on personal welfare than on the richness of social relationships. Social interaction profoundly affects us, influencing both our minds and bodies: as illustrated by the Harvard Study of Adult Development, initiated in 1938, which monitored hundreds over decades, highlighting that intimate bonds are more reliable predictors of prolonged, fulfilling lives than socioeconomic status, IQ, or genetic makeup. Too often, modern lifestyles allow us to overlook a well-established truth: comrades merit our dedication. The social brain hypothesis anchors this straightforward truth in an origin story.

It also positions our species’ origin in a wider framework. Cerebral growth commenced well before the rise of Homo sapiens. All primates manifest a link between group size and cerebral cortex dimensions, indicating that a large brain has always been essential for managing many social connections.

This, in turn, suggests the eventual emergence of a human-like entity was unavoidable.

RELATED STORIES

—Neuroscientist says that the evolution of existence on this planet ‘almost certainly’ gave rise to human intellect

—Minuscule ‘brains’ developed in laboratories could gain awareness and suffer — a situation we’re unprepared for

—Neuroscientists uncover ‘engine of consciousness’ concealed within monkeys’ brains

The original development of eukaryotes utilizing energy extraction from other entities established the path toward the human species — inevitably giving rise to an entity capable of controlling fire, and even nuclear fission. The social brain theory indicates something similar at its most fundamental level. Once primates were engrossed in an impulse to expand their societies and brains, an entity was bound to evolve with adequately sizable communities and sophisticated enough brains to communicate, devising symbolic and abstract classifications — leading, ultimately, to a semblance of culture, art, and societal structures.

This final essence — abstract, symbolic communication passed from person to person through cultural means — fulfills the blueprint of a human being that had gradually solidified over eons. To grasp the import of language for our lineage, an interlude is required. Most texts about human evolution launch directly from this point, navigating through the past million years to the present, where apes slowly transformed into several Homo species, now with only one survivor — the “wise” species, or sapiens. Our quest, instead, takes us inward, into the human brain, delving into the deluge of electrical signals flowing through this remarkable instrument that governs our conscious thoughts.

$30.22 at Amazon

One Hand Clapping: Unraveling the Mystery of the Human Mind

“One Hand Clapping” borrows from neuroscience, evolution, philosophy and an extensive compendium of cultural touchstones to delve into the way Earth’s chronicle culminated in our individual minds. The publication brings to light the profound connection between our awareness and nature’s inherent characteristics.

TOPICSbooks

Nikolay KukushkinProfessor and author

Nikolay Kukushkin serves as a Clinical Associate Professor of Life Science and holds a research fellowship at the Center for Neural Science, NYU. He earned a D. Phil. in Biochemistry from the University of Oxford (UK) and a B. Sc. in Biology from St. Petersburg State University (Russia). He authored the bestselling, award-winning book “One Hand Clapping: Unraveling the Mystery of the Human Mind” (Prometheus/Swift Press), examining the origins of human awareness.

With contributions from

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: The neuroscientists that learned to control memories in rodents

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA from our long-lost ancestors affects our health today

Chimps ‘think about thinking’ in order to weigh evidence and plan their actions, new research suggests

Some people love AI, others hate it. Here’s why.

‘Artificial intelligence’ myths have existed for centuries – from the ancient Greeks to a pope’s chatbot

Switching off AI’s ability to lie makes it more likely to claim it’s conscious, eerie study finds

Latest in Neuroscience

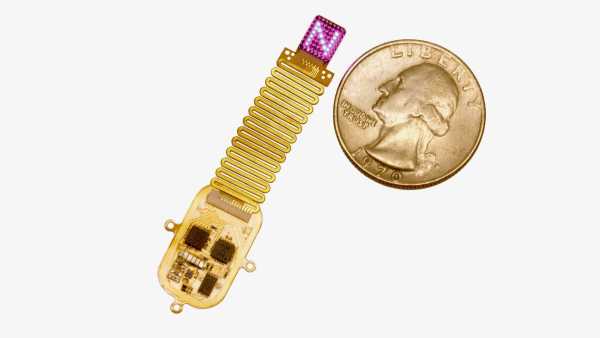

Tiny implant ‘speaks’ to the brain with LED light

Neuroscience word search — Find all the parts of the brain