Video World’s largest cog ship discovered off Denmark coast

In Denmark, archaeological experts revealed the globe’s biggest medieval cog ship, unearthed near Copenhagen after 6 centuries submerged. (Credit: Vikingeskibsmuseet)

NEWYou can now listen to Fox News articles!

Recently, Danish archaeological experts announced a noteworthy historical finding. They located the remains of the world’s most massive cog ship in the waters near Copenhagen, following nearly 600 years.

The declaration, issued by the Viking Ship Museum in Roskilde in late December, indicated that the ship was located in the Øresund, a channel positioned between Denmark and Sweden.

During seabed assessments prior to the beginning of construction on Copenhagen’s Lynetteholm project, divers located the cog — a form of medieval freight vessel.

“From the very first submersion, the nautical archaeologists felt they had detected something exceptional,” expressed the Viking Ship Museum in their announcement.

“And as they cleared away centuries’ worth of sediment and sand, the form of an extraordinary discovery became visible. Not merely another shipwreck, but the most sizable cog ever brought to light — a vessel symbolizing one of the most cutting-edge ship designs of its era and the groundwork of medieval commerce.”

Wood dating analysis demonstrated that the vessel was crafted using wood from Pomerania and the Netherlands. (Vikingeskibsmuseet)

The vessel, dubbed Svælget 2, was constructed in 1410.

It spans approximately 92 feet in length, 30 feet in width, and 20 feet in height, boasting a projected cargo capacity of around 330 tons.

Researchers determined the ship’s age via wood dating analysis, revealing it had been assembled using timber sourced from Pomerania, located in present-day Poland, and the Netherlands.

The vessel “stands as the biggest illustration of its kind ever uncovered anywhere across the globe,” as stated by the museum.

“The cog was a productive vessel class capable of being operated by a noticeably small crew, even when carrying substantial loads.”

As per Danish archaeological experts, the remains of Svælget 2 constitute the biggest cog ship ever unearthed globally. (Vikingeskibsmuseet)

“[The cog] was the prime vessel of the Middle Ages. … It revolutionized trade dynamics. Where previously, long-distance commerce had been restricted to premium goods, now everyday commodities could be transported across vast stretches.”

The vessel withstood the centuries due to the sand that shielded it from the elements. Archaeologists were especially taken aback to find that the ship still had its rigging, encompassing the network of cables, ropes, and fittings that propped up its mast.

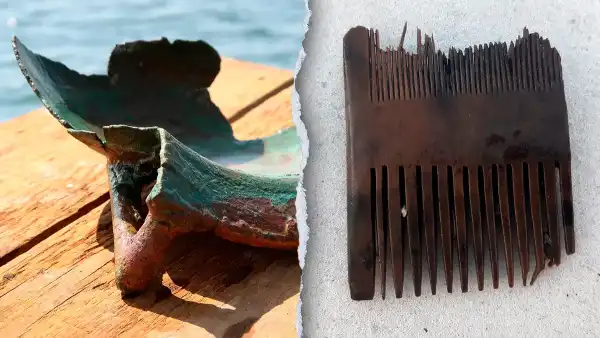

Divers also retrieved a plethora of individual belongings, such as utensils, footwear, combs, and prayer beads employed daily by the sailors.

Remarkably, archaeologists discovered the ship’s galley constructed from bricks, wherein the crew prepared meals over an exposed fire pit — a rare indulgence during maritime life.

Archaeologists recovered routine personal effects — including combs utilized by sailors aboard the massive cog ship. (Vikingeskibsmuseet)

Though no sign of freight has been located, the museum suggested that barrels containing salt, bundles of fabric, and lumber were probable possibilities.

“Despite the absent cargo, it is clear that Svælget 2 served as a merchant vessel,” the museum supplemented. “Archaeologists have not detected any indications of military application.”

The prevalence of cogs of this magnitude in Northern Europe during that era remains undetermined.

“We lack precise knowledge on this,” Otto Uldum, nautical archaeologist and head of the excavation, communicated to Fox News Digital.

“To come across a cog lost at sea in this well-preserved state is quite unusual.”

“There is a definite inclination for cogs to be constructed progressively larger via this methodology, [for instance, from] 1200 to 1400,” Uldum remarked.

“Given the scarcity of cogs dated so late, we presume that most cogs entering the Baltic from the North Sea were approximately [82 feet] long, with Svælget 2 representing an upper boundary.”

Uldum was notably impressed by the recovery of the ship’s stern castle — the initial archaeological confirmation that such elevated structures, commonly portrayed in medieval illustrations, genuinely existed.

He also described the cog’s state of preservation as “highly unique,” noting that similar discoveries in the Netherlands had been excavated in guarded, reclaimed seabed regions rather than open waters.

“To encounter a cog lost in oceanic waters in this condition of preservation is exceedingly rare,” the excavation’s lead stated. (Vikingeskibsmuseet)

“To discover a cog lost at sea while retaining this degree of preservation is exceptionally rare — and the circumstance that it was in transit on the open sea when it was lost places it among a select number of other shipwrecks,” Uldum added.

The archaeologist conveyed his hope that more detailed analysis of the ship’s unearthed items, encompassing mammal and fish bones, will provide insight into the dietary habits of the crew on board.

The combs, footwear, and cooking implements demonstrate that “the vessel was exceptionally well-appointed, and that the sailors enjoyed a relatively comfortable existence,” Uldum appended.