(Photo courtesy of Alyssa A. Goodman/Harvard University)

A new study suggests that, like a ship moving through changing weather at sea, our solar system passes through different galactic environments as it circles the center of the Milky Way, and one of them may have had a lasting impact on Earth's climate.

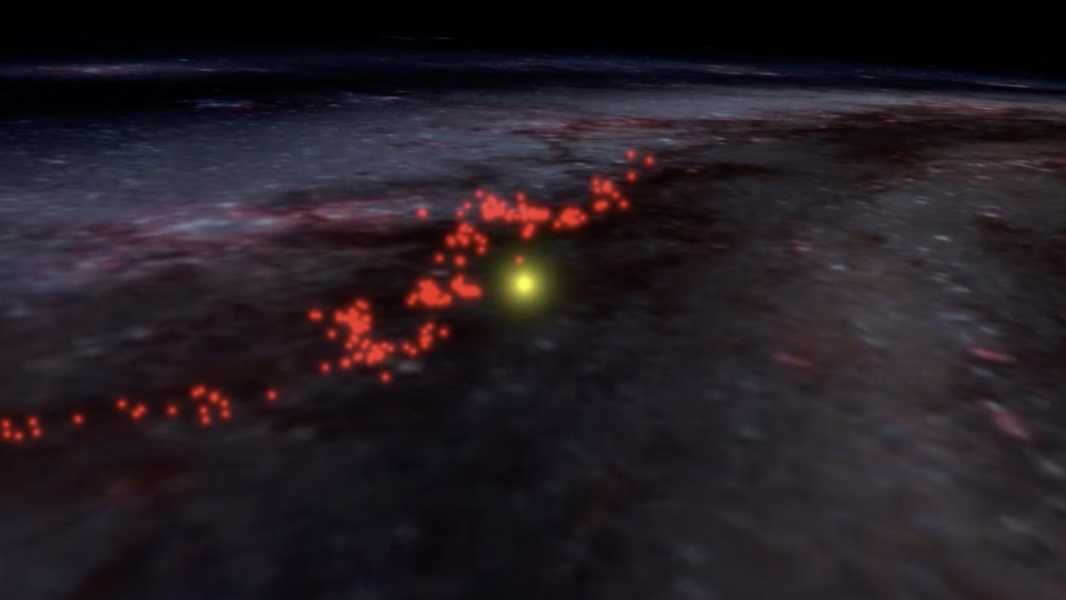

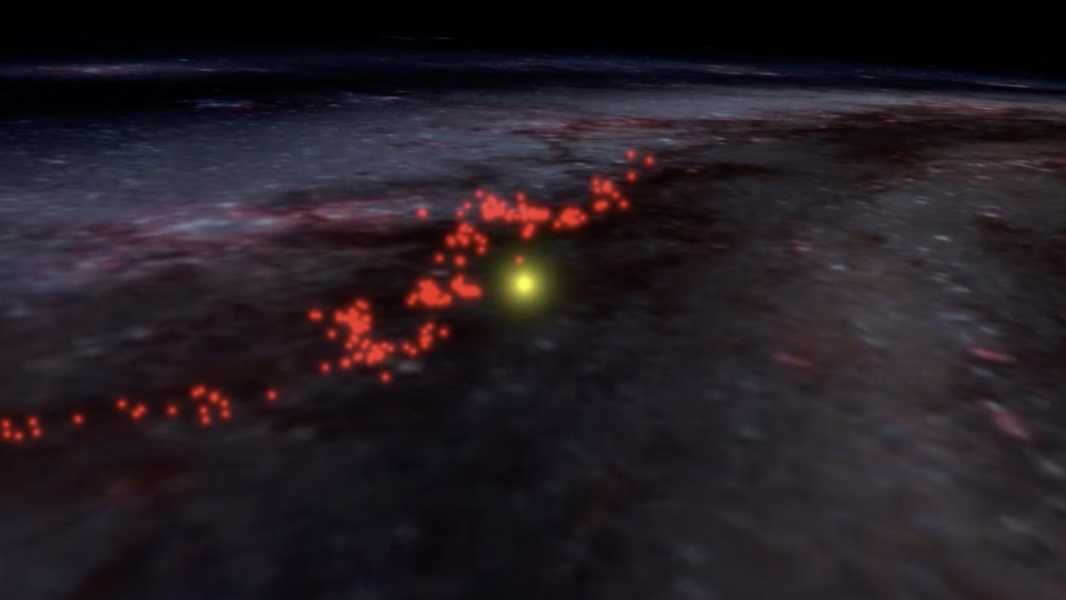

Data from the European Space Agency’s recently completed Gaia mission show that about 14 million years ago, our solar system was moving through a dense star-forming region in the direction of the constellation Orion. The region is part of a vast network of star clusters stretching nearly 9,000 light-years across and forming a structure known to astronomers as the Radcliffe Wave, named after the Harvard Radcliffe Institute in Massachusetts where its existence was confirmed.

When our solar system passed through this structure millions of years ago, it may have encountered an increased flow of interstellar dust. The timing of this event coincides with Earth’s transition from a warmer to a colder climate, reflected in the expansion of the Antarctic ice sheet. This raises the possibility that the collision may have contributed to the climate shift in conjunction with several other factors and ongoing processes, a new study suggests.

Further research could confirm this theory. If unusually high levels of radioactive elements — expected with a significant influx of dust — are ever found in our planet’s geologic record, it would strengthen the study’s hypothesis, “because you’d have a geologic signature and an astronomical perspective that could explain it,” lead study author Efrem Makoni, a PhD student in astrophysics at the University of Vienna, told Live Science.

He and his colleagues presented their findings in a paper published last month in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics. But finding the crucial piece of evidence in our planet’s geologic record — a 14-million-year spike in a rare isotope of iron known as iron-60, which is typically produced in supernovae but is extremely rare on Earth — will be difficult.

“Studying the past is hard — whether you’re doing it in space or Antarctica,” Teddy Kareta, an astronomer at the Lowell Observatory in Arizona who was not involved in the new study, told Live Science. “It’s a really exciting scenario that they’ve presented, but finding concrete evidence that this has implications for Earth’s climate, or assessing the increase in dust flow that the solar system has experienced, could take quite a long time and require a significant effort from all the sciences.”

“We're actually talking about yesterday.”

Although the Radcliffe Wave is located at the edge of our galaxy, just 400 light years away, astronomers only noticed it in 2020 thanks to the Gaia telescope's ability to determine the distances and velocities of known star-forming gas clouds, allowing them to create a 3D map of the Sun's neighborhood.

Using the latest Gaia data, Maconie and his team modeled the journey of 56 young star clusters associated with the Radcliffe Wave, tracing both their current orbits in the Milky Way and their paths to their births, which were inferred from their natal molecular clouds. This allowed the researchers to essentially “go back in time and see where they were in the past relative to the solar system,” Maconie said.

The researchers found that our solar system was at its closest point to the Orion region about 14 million years ago, coming within 65 light-years of at least two local, dusty star clusters: NGC 1980 and NGC 1981. At that time, our solar system was largely the same as it is today; Earth and the other planets formed more than 4 billion years ago. But from a cosmic perspective, “we’re really talking about yesterday,” Maconie added.

Modeling shows that our solar system has been around for about 1 millisecond

Sourse: www.livescience.com