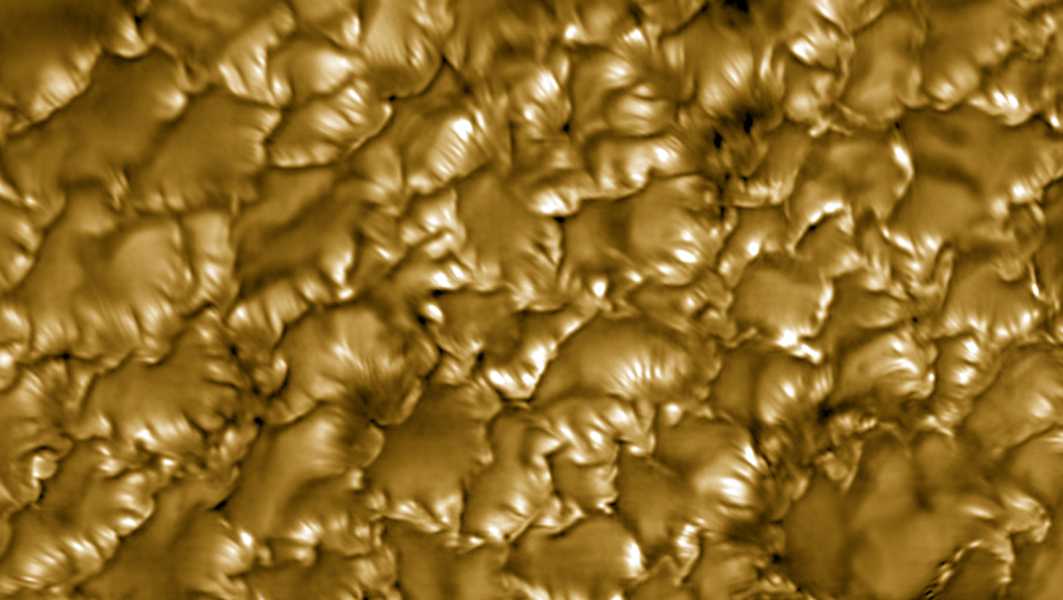

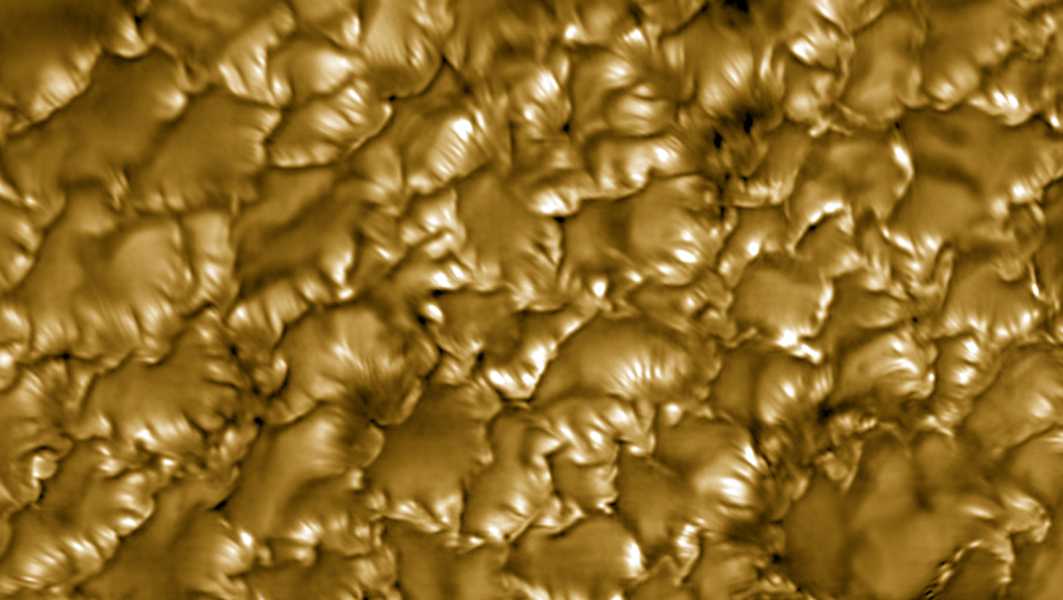

(Image credit: NSF/NSO/AURA)

The National Science Foundation's (NSF) Daniel K. Inouye Solar Telescope, located atop Haleakala on the island of Maui, Hawaii, has produced the sharpest images ever of the solar surface.

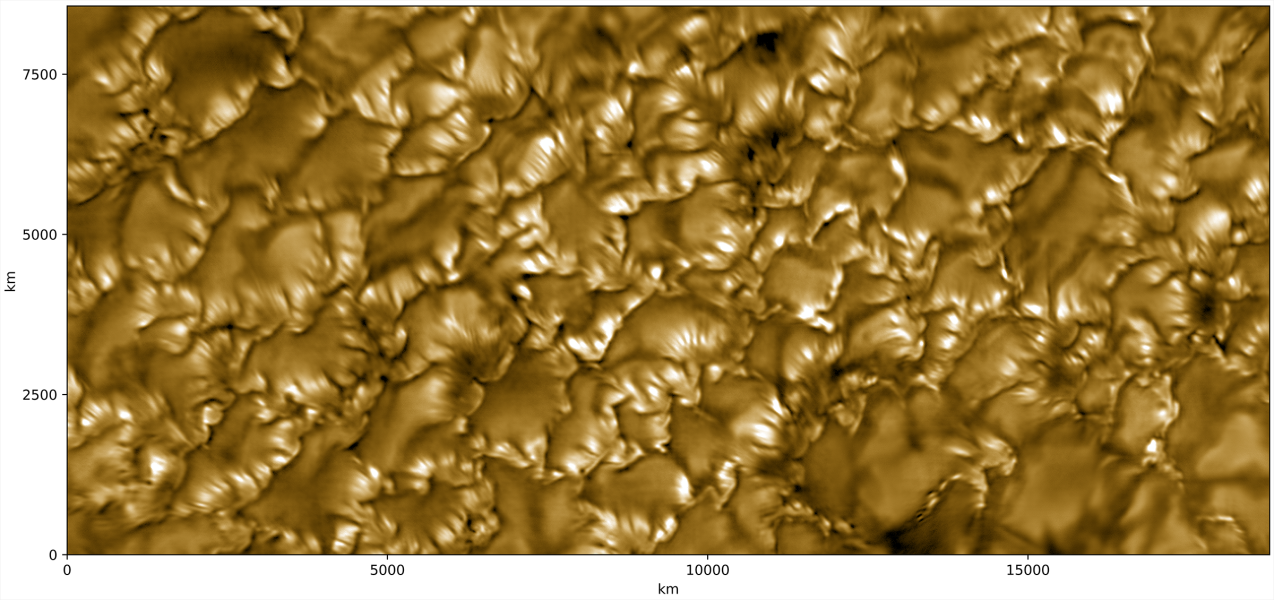

According to the National Solar Observatory (NSO), which operates the solar telescope, the images show tiny bright and dark lines (known as streaks) in the thin gaseous layer of the sun's atmosphere called the photosphere.

“In this work, we study for the first time the small-scale structure of the solar surface at an unprecedented spatial resolution of only about 20 kilometers [12.4 miles], which is comparable to the length of Manhattan Island,” said David Kuridze, lead author of the study and an NSO scientist. “These streaks are traces of small-scale variations in the magnetic field.”

You may like

- The world's largest solar telescope has acquired a powerful new camera, revealing a stunning view of a sunspot the size of a continent

- For the first time in history, people saw the lower part of the sun (photo)

- Watch creepy 'UFOs' and a solar 'cyclone' form in ESA's stunning new video of the Sun

Ultra-fine lines appear in the sharpest images of the Sun ever documented. These lines are known as photospheric bands and are caused by the dynamics of the Sun's magnetic field.

The stripes appear as alternating bright and dark lines along the walls of solar granules — convection cells that transfer heat from the sun's interior to its surface. The patterns are caused by magnetic fields that move and ripple like fabric fluttering in the wind.

When light from the hot granule walls passes through these magnetic “curtains,” changes in magnetic field strength cause changes in brightness, effectively tracking the underlying magnetic structures. If the magnetic field is weaker than the surrounding ones, it appears darker; if it is stronger, it glows brighter.

The stripes are therefore thought to be indicators of subtle but powerful magnetic fluctuations that alter the density and opacity of the solar plasma. These small shifts can only be detected by the telescope's Visible Broadband Imager (VBI), which operates in the G-band, a specific range of wavelengths

Sourse: www.livescience.com