The underwater data centre off the coast of Hainan was a pilot project before a more advanced centre is now being built off the coast of Shanghai. (Image courtesy of Shanghai Hailanyun Technology)

China is betting on artificial intelligence, cloud computing, and other digital technologies to grow its economy, and much of that bet involves rapidly building data centers to boost computing power. But these massive server complexes are increasingly power hungry, and each one consumes hundreds of thousands of gallons of water every day to dissipate the heat they generate.

That means these facilities — in China and beyond — will increasingly compete with water needs directly tied to human survival, from agriculture to daily drinking. Many companies have located their data centers in some of the driest regions of the world, including Arizona, parts of Spain, and the Middle East, because dry air reduces the risk of humidity damaging equipment, according to an investigation by nonprofit journalism group SourceMaterial and The Guardian. Partly to address the water issue, China is now locating data centers in the wettest place: the ocean. In June, construction began on an underwater wind-powered data center about six miles off the coast of Shanghai, one of China’s AI hubs.

“China’s ambitious approach signals a bold shift toward low-carbon digital infrastructure and could impact global norms around sustainable computing,” said Shabrina Nadhila, an analyst at energy think tank Ember who has researched data centers.

You may like

-

China Begins Building AI Supercomputer in Space

-

Hurricanes and sandstorms can be predicted 5,000 times faster thanks to new Microsoft AI model

-

Advanced AI reasoning models generate up to 50 times more carbon dioxide than conventional LLM models

Keeping data centers cool

Data centers store information and perform complex calculations for companies whose increasing automation is constantly increasing these needs. These facilities consume enormous amounts of electricity and water because their servers run continuously and are located in close proximity to each other, and they also generate waste heat that can damage equipment and destroy data. So they must be constantly cooled.

About 40% of the electricity consumed by a typical data center is spent on this purpose. Much of this energy is used to cool water, which is sprayed into the air around the servers or evaporated near them, reducing their temperature. This water can come from underground, from nearby rivers or streams, or from treated wastewater.

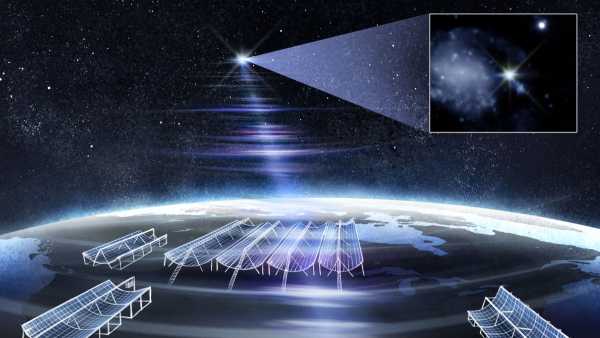

An artist's rendering of a wind-powered underwater data center under construction off the coast of Shanghai.

Instead, underwater data centers pump seawater through pipes over a radiator located on the back of the server racks, absorbing and dissipating heat. Hailanyun, the company behind the Shanghai data center and sometimes called HiCloud, says an assessment conducted with the China Academy of Information and Communications Technology shows that its design uses at least 30% less electricity than land-based data centers, thanks to natural cooling.

The Shanghai center will also be connected to a nearby offshore wind farm, which will provide 97 percent of its power, Hailanyun spokesman Li Lanping said.

The first phase of the project is designed for 198 server racks, which can accommodate between 396 and 792 AI-enabled servers, Li said. It is scheduled to go live in September. The computing power is expected to be enough to complete training equivalent to GPT-3.5 — the large language model released by OpenAI in 2022 and used to fine-tune ChatGPT — in a day. However, the Shanghai Hailanyun center is small compared to a typical land-based center: A mid-scale data center in China typically has up to 3,000 standard racks, while a superscale one can contain more than 10,000.

Ahead of the US

Hailanyun’s $223 million Shanghai gambit is based on technology pioneered by Microsoft more than a decade ago as part of Project Natick, which involved sinking a shipping container-sized capsule containing more than 800 servers 128 feet (38 meters) below the surface off the coast of Scotland. When Microsoft retrieved the capsule two years later, it found that underwater data centers were “robust, practical, and energy efficient.”

A 2020 Microsoft press release also cited fewer broken servers compared to land-based data centers because the container was sealed and filled with nitrogen, which is less corrosive than oxygen. The lack of people also meant that the equipment avoided physical contact or movement that could damage it in a land-based center, the company said.

Hailanyun will deploy the first phase of its underwater data center in the ocean off the coast of Hainan in December 2022.

However, Microsoft has reportedly put Project Natick on hold. A company spokesperson did not respond to questions about whether the project had been shut down. Instead, the company issued the following statement: “While we do not currently have data centers in the water, we will continue to use Project Natick as a research platform to explore, test, and validate new concepts related to data center reliability and resilience.”

Hailanyun is aiming to beat American companies: if the Shanghai project is successful, Li expects his company to become a springboard for a large-scale deployment of offshore wind-powered data centers, backed by the Chinese government.

Zhang Ning, a research fellow at the University of California, Davis who specializes in next-generation low-carbon infrastructure, notes that Hailanyun has gone from a pilot project in Hainan in December 2022 to commercial deployment in less than 30 months — “something that Microsoft’s Project Natick never attempted to do.”

Environmental issues

Despite the obvious benefits of underwater data centers, some concerns remain, particularly about the potential environmental impact. Microsoft researchers found that their module caused local warming in the sea, although the impact was limited. “The water just a few meters downstream of the Natick vessel would warm by a few thousandths of a degree, at most,” they wrote.

But other researchers argue that flooded data centers could harm aquatic biodiversity during a marine heatwave, a period of unusually high ocean temperatures. In such cases, the water leaving the ship would be even warmer and contain less of the oxygen that aquatic creatures need to survive, according to a 2022 paper.

Two watertight containers containing servers and other equipment will be launched off the coast of Hainan as part of China's first commercial underwater data center in November 2023.

Another concern is security. A 2024 study found that underwater data centers could be disrupted by certain noises generated by underwater acoustic systems, raising concerns about malicious attacks using sound.

In response to such concerns, Hailanyun says its underwater data centers are “green,” citing an assessment conducted at one of its test sites in the Pearl River in southern China in 2020. “The heat dissipated by the underwater data center caused the surrounding water temperature to rise by less than one degree,” Li says. “It had virtually no significant impact.”

RELATED STORIES

— Meta-AI Takes First Step Towards Superintelligence — and Zuckerberg Will No Longer Release the Most Powerful Systems to the Public

— How an AI assistant is changing teen behavior in surprising and sinister ways

— OpenAI's ChatGPT agent can control your PC to perform tasks on your behalf, but how does it work and what's the point?

The concept of underwater data centers appears to be gaining more and more appeal outside of China. Other countries, including South Korea, have also announced plans to pursue it, while Japan and Singapore are considering creating data centers floating on the ocean surface.

Zhang argues that whether other coastal areas follow this trend depends less on technical feasibility than on how quickly potential operators can address regulatory, environmental and supply chain issues that “China is now addressing on a large scale.”

This article originally appeared in Scientific American. © ScientificAmerican.com. All rights reserved. Follow on TikTok and Instagram, X and Facebook.

TOPICS China

Yu Xiaoying, freelance journalist

Yu Xiaoying is a freelance journalist based in London. She writes and reports on climate change and the transition to clean energy.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be prompted to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

China Begins Building AI Supercomputer in Space

Hurricanes and sandstorms can be predicted 5,000 times faster thanks to new Microsoft AI model

Advanced AI reasoning models generate up to 50 times more carbon dioxide than conventional LLM models

AI is constantly “hallucinating”, but there is a solution

'Like a creeping mold spreading across the landscape': study finds isolated arid areas around the world are coalescing into 'mega-arid' regions at alarming rates

Your devices are sharing data with AI assistants and collecting personal data even when they're asleep. Here's how to find out what you're sharing. Cutting-edge technology

Meet the Drumming Robot: Scientists are teaching AI to play drums in the style of Linkin Park and AC/DC, but it looks like it still needs a lot of practice.

IBM and NASA create first-of-its-kind AI capable of accurately predicting powerful solar flares

Secret X37-B space plane to test quantum navigation system scientists hope will one day replace GPS

Your household gadgets may soon be able to do without batteries – scientists have created tiny solar cells that can be powered by indoor light.

OpenAI ChatGPT Agent can take control of your PC, performing tasks on your behalf, but how does it work and what's the point?

Japan's Energy Breakthrough Could Be 'A Step Towards a Fully Wireless Society' Latest News

Mysterious 300,000-year-old Greek cave skull was neither human nor Neanderthal, study finds

James Webb Telescope Captures Brightest FRB Ever Recorded

'We never had concrete evidence': Archaeologists discover Christian cross in Abu Dhabi, proving 1,400-year-old settlement was once a monastery

If 'pregnancy robots' were a reality, would you use them?

Surprising results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater are formed in the stratosphere.

China's $14,000 Pregnancy Robot Doesn't Exist. But Is Such Technology Possible? LATEST ARTICLES

1X-ray telescope finds something unexpected in black hole's 'heartbeat'

Live Science is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web Notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,type-crosspost,exclude-from-syndication,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com