“`html

Neurobiologists were able to alter the actions of rodents by stimulating their brains with lasers to trigger memories.(Image credit: onurdongel/Getty Images)

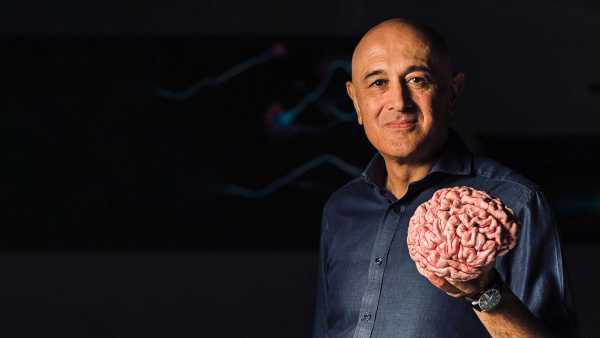

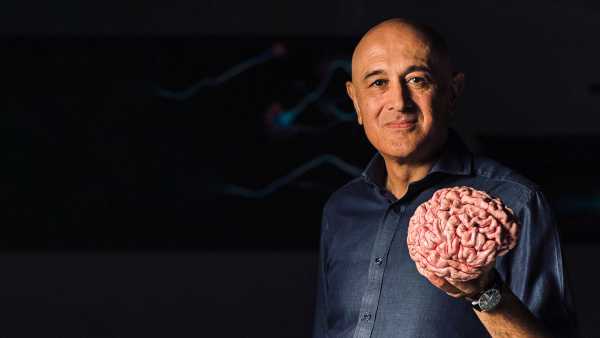

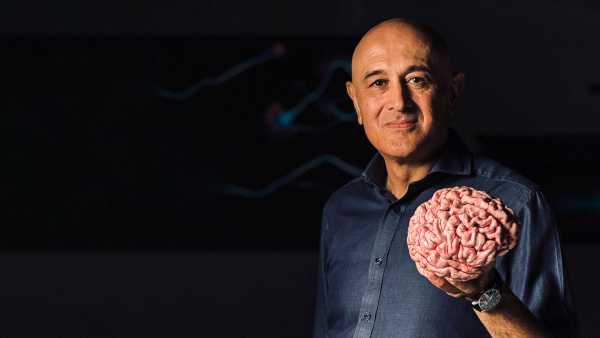

Is it possible to modify undesirable memories? In this tailored segment from “How to Change a Memory” (Princeton University Press, 2025), writer and brain expert Steve Ramirez tells of the occurrences that steered him and his fellow workers to realize memories could be artificially governed in rodents, by connecting directly to the brain.

Our body frequently compels us to brace for several possibilities amid doubt. It’s favorable to be concerned with such possibilities because it motivates us to devote effort, to adequately prepare for a specific nerve-racking situation. All the same, sometimes the levels of strain skew to such an extent that pathologies of the mind start to materialize.

You may like

-

In ‘Secrets of the Brain,’ Jim Al-Khalili explores 600 million years of brain evolution to understand what makes us human

-

REM sleep may reshape what we remember

-

Map of 600,000 brain cells rewrites the textbook on how the brain makes decisions

The significant variance in how anyone gets to a condition of worry, as an example, underscores that our minds house numerous meandering routes that can eventually lead to the same sensation. We’re all subject to triggers in life, but such triggers hinge on experience — on recall. When such differences impact our disposition, thinking, actions and general daily performance, they’re then assigned to a grouping. Moreover, if noted impairments possess comparable features, then this grouping itself is part of a wider categorization — that of a psychological illness.

As I came into my concluding year of postgraduate education, I was starting to realize how prevalent a worried emotion can truly be. Exactly as my own pressures in life began to mount — finishing my paper, drafting grants and job submissions, pursuing the apparently infinite pursuit of purpose as a scientist and individual — my mother equally experienced a rapid return of anxious instances that ultimately resulted in frequent panic attacks. Upon learning about her life long involvement with the unstable sensation that worry represented for her, I began to value the periodic character of these emotions. I kept dwelling on her panic episodes and how annoying it felt to lack the capacity to activate “off” on some of the most ruining instances one might experience.

My concluding undertaking in postgraduate education would aim to deliberately trigger positive memories to diminish the signs linked with worry and despondency. It would turn out to be my most intimate scientific undertaking, a direct manner for me to participate in the fight beside my mother and to acknowledge her for being my leading example. Should my study somehow spark novel restorative approaches that may be helpful for alleviating such weakening ailments, then my effort will have realized an even more profound, personally relevant purpose.

My research partner Xu Liu and I were interested in embracing a mind centered strategy to our newest undertaking. Would recall itself be artificially governed in rodents, by connecting directly to the mind to reestablish neural and behavioral harmony for therapeutic application?

Fortunately, our endeavor held a scientific foundation in humans — within an influential article by psychologist Barbara Fredrickson and fellow researchers entitled “The undoing effect of positive emotions.” This study highlighted the capacity of positive emotions to undo the physiological consequences that adverse emotions exert on the mind and frame.

The undoing theory proposes that positive emotions may be utilized for over and above simply feeling delighted. They could be employed to enable us to get out of bed each day; seek satisfaction; transform how we consider and communicate with ourselves and those around us; and oppose, or at the very least regulate, adverse emotions. As human participants were anxious and then watched film segments that induced fulfillment and amusement, their systems bounced back in favorable ways: their stress induced upticks in cardiovascular function, for instance, reverted to standard faster than when they observed impartial or miserable film segments. Suitably, this shows a definite physical link between sentiments of positivity and their straight effects on our physiology.

Xu and I desired to elaborate on this effort by verifying a plausible restorative ability of positive memories by jump starting their biology from the inside of the mind. We situated our subjects inside a box having a pair of minute spouts on differing ends: one capable of dispensing sweet water as the subjects consumed it and a further capable of dispensing simple water. This is recognized as the saccharose preference test. Ordinarily, rodents prefer sweet water beyond simple water, like people will usually discover sugary fluids preferable to an insipid fluid. Then again, rodents by means of depression and worry associated actions commonly show a 50:50 preference. They show zero preference at all.

You may like

-

In ‘Secrets of the Brain,’ Jim Al-Khalili explores 600 million years of brain evolution to understand what makes us human

-

REM sleep may reshape what we remember

-

Map of 600,000 brain cells rewrites the textbook on how the brain makes decisions

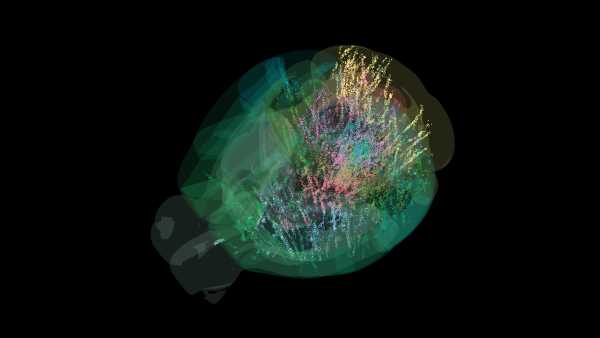

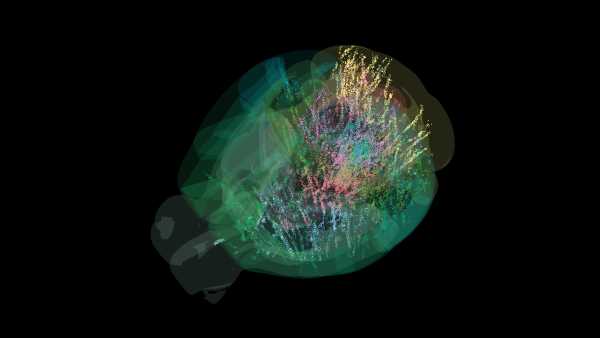

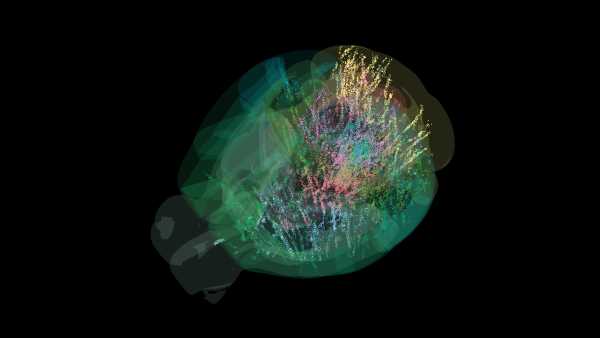

As expected, the subjects exhibiting worry and despondency linked behavior consumed from each of the spouts randomly over a quarter hour. Like with Project X — our initial effective attempt at MIT to artificially govern memories inside the rodent mind — the only action remaining was pressing a switch capable of activating our lasers and optogenetically awakening a memory from within.

Click.

The deep blue laser beam flickered all through the mouse’s hippocampus, awakening — triggering — cells retaining a favorable memory. I recall reasoning that our optogenetic arousal was an elegant, cutting-edge Proustian madeleine, one capable of activating the rich reminder of occurrences gone by. Grant me leeway as I add a romantic aspect to this instant: the rodent perked up immediately, as though a quiver stretched from its mind to its body, and commenced assessing the setting to determine which spout to head to initially.

Something uncommon was unfolding. I picture the rodent sensing the memory flood all its senses, strangely cut off and without a trace of its beginning, as the essence of such sensations lived within the rodent as greatly as it was the rodent. And instantly the positive memory revealed itself completely within a few moments, the now motivated rodent checked each spout by means of some sniffing, accompanied by a tasting experiment.

The key to reversing abnormal behavior was embedded within their positive memories all along.

As it identified the spout containing the sweet water, the rodent commenced consuming energetically, so greatly so that it consumed as much sweet water as our control subjects. In lower than an hour, Xu and I noticed reactivating positive memories restored our subjects’ behavior to a wholesome normal. Equally thrilling, reactivating positive memories equally switched on numerous areas of the mind concerned with rewarding experiences and motivation.

The key to reversing abnormal behavior was embedded within their positive memories all along. For so long as the laser beam shone its sapphire glow in their minds, the subjects were compelled to persist in consuming their sweet water payoff. All this originating from triggering cells in the hippocampus. Or expressed by means of reduced fiction: the rodents gained a sugary reward.

In the following weeks, Briana Chen, one of my talented undergraduates, gathered an extensive empirical dataset for the effort, which included a thrilling narrative diversion: as she artificially reactivated positive memories on two occasions per day, or “repeatedly,” for around one week, not only did this permanently mitigate signs we thought were associated with despondency and worry, but it equally fostered the development of new cells inside the mind. Positive memories held both fleeting and lasting advantages, all the way from cells to behavior.

Inspired by the neurocentric Research Domain Criteria (RDoC) tactic to handling the mind, our expectation was that the biological strength of positive memories — for example medications — could educate cognitive behavioral approaches to handling conditions of the mind. This undertaking held meaning for me on a personal scale: I reflected on my mother’s panic episodes and the notion that she could possibly evade the kind of overwhelming worry that denies an individual of peace.

Positive memories stand as some of the most potent biological tools offered inside our minds. Back home, my mother and I featured an abundance of them — one we both recall originates from as I was a teenager, and we were going to visit her parents inside El Salvador.

One morning, my cousins, mom and grandparents all walked down a hill following the house my mom developed within to proceed swimming within the community pond. My cousins persisted in motivating me to jump from a cliff into the pond, and my mother continued saying I had no obligation to.

Like her, I lacked any thrill-seeking tendencies because, oh I don’t know, potentially my inherent biology perceived something, as “please evade falling to earth” played continuously inside my brain. She could perceive that I felt frightened, and following a few moments she indicated, to my surprise, that we should jump at once. We clasped hands and tiptoed to the perimeter — uno, dos, tres — we were in the air! Moments after, we came out of the water laughing in delightful amazement at our newfound daring.

RELATED STORIES

—Fresh research reveals the causes behind time appearing to travel quicker the older we become

—When your brain becomes ’empty,’ your brain operation looks akin to a deep slumber, scans uncover

—Might your brain run dry on recollection?

Neuroscience shows us that such a memory holds each of the ingredients of life’s sweet treat that encourage us to feel satisfied. In line with an RDoC outlook, my cognitive and valence systems are each interacting to generate the riches from this instance: the cognitive system facilitates the memory of springing off of a cliff, which at first produced sentiments of concern by way of the adverse valence systems, which are instantly almost immediately countered by sentiments of reward through the positive valence systems.

A once fearful instance stands as a memory of victory beside my mother. It stands as the solitary time I may recall when we both grabbed a true jump of assurance, therefore we treasure the memory for instance of what our minds may attain as a group. Countless small life moments similar to these, packaged perfectly into countless memories that we hold on to make up the beautiful aspects of life.

Adapted from “How To Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest To Alter The Past”. Copyright © 2025 by Steve Ramirez. Reprinted by permission of Princeton University Press.

How to Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest to Alter the Past (Hardcover) — $29.95 on Amazon

A uniquely personal description of the new study of recollection control through one of today’s main innovators in the field.

Steve RamirezLive Science Contributor

Steve Ramirez has been spotlighted on CNN, NPR, and the BBC and throughout main guides for example The New York Times, National Geographic, Wired, Forbes, The Guardian, The Economist, and Nature. A prized neuroscientist who has delivered TED speeches on his innovative effort on recollection manipulation, he acts as associate professor of psychological and brain sciences at Boston University. His initial book, “How to Change a Memory: One Neuroscientist’s Quest to Alter the Past” is available now.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

In ‘Secrets of the Brain,’ Jim Al-Khalili explores 600 million years of brain evolution to understand what makes us human

REM sleep may reshape what we remember

Map of 600,000 brain cells rewrites the textbook on how the brain makes decisions

Scraps of ancient viruses make up 40% of our genome. They could trigger brain degeneration.

Tiny ‘brains’ grown in the lab could become conscious and feel pain — and we’re not ready

Sourse: www.livescience.com