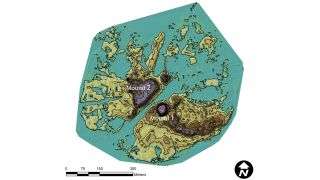

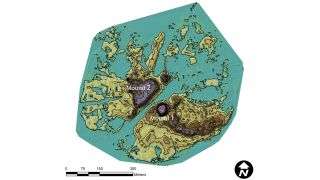

A lidar map showing the geography and location of Mount Key on Florida’s Gulf Coast.

Laser and radar technology has revealed the 454-year-old remains of a Spanish fort on an island off the Gulf Coast of Florida, a new study finds.

The fort, known as Fort San Antón de Carlos, was home to one of the first Jesuit missions in North America. The Spanish built it in 1566 in the capital of a powerful Native American kingdom controlled by the Calusa people. Today, the site is known as Mound Key, an island in Estero Bay.

Historical Spanish documents suggested that the Calusa capital and Fort San Antón de Carlos (named for the Catholic patron saint of lost things) were on Mound Key. But it wasn’t until archaeologists used laser technology known as lidar (light detection and ranging) and ground-penetrating radar that they located the fort’s remains.

“Archaeologists and historians had visited the site and collected pottery from the surface, but until we found physical evidence of the Calusa king’s house and the fort, we could not be absolutely certain,” William Marquardt, curator emeritus of South Florida archaeology and ethnography at the Florida Museum of Natural History, said in a statement.

Lidar was essential to this project, as it helped map the site with lasers, which gave the archaeologists a detailed view of the site’s geography and structures. Likewise, ground-penetrating radar revealed the exact location of the buried structures. This radar technique works when an operator pushes a lawnmower-like vehicle over a site, and the device shoots FM radio waves into the ground. When these waves hit structures — in this case, the fort’s remains — the waves bounce back, allowing researchers to map any subterranean features.

When the team excavated the site, they found the fort’s remains as well as ceramic sherds and beads.

The fort, they found, is the oldest known example of “tabby” architecture in North America, meaning that its walls were made out of shell concrete. This material is made when lime from burned shells is mixed with sand, ash, water and broken shells, the researchers said.

The Spaniards used primitive tabby architecture at Mound Key, utilizing it as a mortar to stabilize posts in the walls of their wooden structures, the researchers said. The English later used tabby in the American colonies, including on Southern plantations.

However, there is more tabby to be found, as the archaeologists have uncovered only part of the fort, they said.

“Seeing the straight walls of the fort emerge, just inches below the surface, was quite exciting to us,” Marquardt said. “Not only was this a confirmation of the location of the fort, but it shows the promise of Mound Key to shed light on a time in Florida’s — and America’s — history that is very poorly known.”

Calusa culture

In 2018, the archaeologists published other findings from the site in the Journal of Anthropological Archaeology on the Calusa king’s house, also on Mound Key. The Calusa were a politically complex culture of fisher-gatherer-hunters who resisted European colonization for almost 200 years, Marquardt said.

The Calusa used shells for nearly everything, including as tools, utensils, jewelry and even in the construction of giant “watercourts,” which kept fish in underwater corrals so that they could be easily fished out to feed a growing population.

The Spanish had a tedious relationship with the Calusa; they abandoned the fort in 1569 after their brief alliance with the Calusa fell apart.

After controlling most of South Florida, the Calusa were hit with European diseases and their power waned. By the time the Spanish turned Florida over to the British, the remaining Calusa had fled to Cuba, the researchers said.

“Despite being the most powerful society in South Florida, the Calusa were inexorably drawn into the broader world economic system by the Spaniards,” Marquardt said. “However, by staying true to their values and way of life, the Calusa showed a resiliency unmatched by most other native societies in the Southeastern United States.”

The study was published online April 22 in the journal Historical Archaeology.

Sourse: www.livescience.com