A pregnant woman wears a mask in Singapore due to dangerous smog levels. New research suggests that air pollution may trigger placental inflammation. (Image credit: Roslan Rahman via Getty Images)

Recent laboratory studies have shown that even short-term exposure to polluted air can alter the structure of the placenta and lead to inflammation in the organ.

Scientists already knew that particles in polluted air can reach the placenta and be absorbed by immune cells.

You may like

-

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

-

A study has found that elective cesarean sections are linked to an increased risk of childhood leukemia: What you need to know

-

Surprising results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater are formed in the stratosphere.

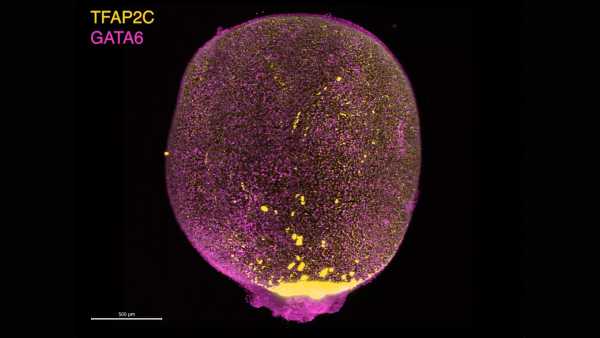

A new study added to this understanding by looking in detail at special immune cells in the placenta called Hofbauer cells to see how their function changed after exposure to compounds found in real air pollution.

“I think this is an important step in filling a gap in what we know from epidemiological studies,” Grigg said.

These studies have shown a link between exposure to pollutants during pregnancy and the risk of preeclampsia, which is associated with high blood pressure. Preeclampsia is associated with impaired blood supply to the placenta and, consequently, low oxygen levels in the organ. Some researchers argue that placental dysfunction is the cause of preeclampsia, but not everyone agrees, as some point to the mother's cardiovascular system. Nevertheless, the placenta is considered a key factor in the development of the disease.

A recent study, published online in March in the Journal of Environmental Sciences, will also appear in the February 2026 print issue of the journal. It used what's known as “ex vivo double placental perfusion,” meaning the researchers collected placentas from full-term pregnancies from volunteers who donated them at birth via cesarean section or vaginally. A total of 13 healthy placentas were donated.

“You can't expose women to air pollution as an experiment,” study co-author Dr. Stefan Hansson, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and senior consultant in obstetrics at Lund University in Sweden, told Live Science. “Therefore, the best model is the placental perfusion system we used.”

After birth, the placenta is connected to an artificial perfusion system that mimics elements of the female reproductive system. “Within 30 minutes, you connect it to an artificial uterus,” Hansson explained. Tubes connected to one side of the placenta represent the mother's circulatory system, while those on the other side represent the umbilical cord, which will connect to the fetus.

You may like

-

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

-

A study has found that elective cesarean sections are linked to an increased risk of childhood leukemia: What you need to know

-

Surprising results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater are formed in the stratosphere.

The tubes deliver nutrients and oxygen to the placentas, maintaining their health for about six hours and mimicking both the maternal and fetal sides of the organ. During this time, scientists can monitor the organ's metabolism, homeostasis, blood pressure, and the behavior of its immune cells.

“This is good because it potentially captures more complex interactions between cells, how fluid and particles move through cells,” Grigg said. By comparison, studying individual placental cells in a test tube is perhaps less realistic.

The researchers then introduced air pollutants into the system to see what would happen. Six placentas were left unexposed to the pollutant for comparison; five placentas were exposed to the pollutant for five hours; one was exposed for 60 minutes; and one was exposed for 30 minutes. Tissue and fluid samples were taken from the system before, during, and after perfusion.

The pollutants themselves were taken from a previous air analysis in Malmö, Sweden, conducted in the spring of 2017. Samples were collected at an intersection with an average annual traffic density of approximately 28,000 vehicles. The team focused on “fine” particulate matter (PM2.5), which includes particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers.

Grigg told Live Science that “the concentrations of particles they're using in the perfusates are almost certainly significantly higher than the very low concentrations that circulate in the body,” based on previous studies. This raises the question of how accurately the doses they tested reflect real-life conditions. “I think that's probably a reasonable limitation,” he said.

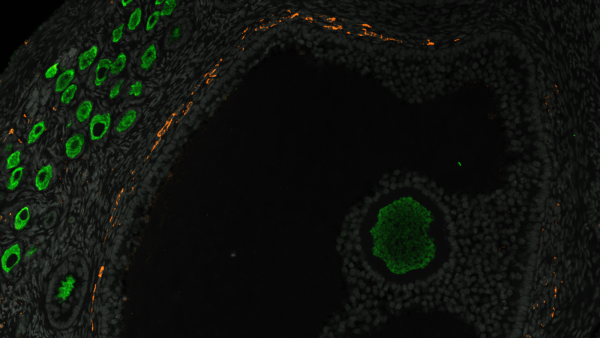

However, at the concentrations studied, the pollutants had a significant impact on the placentas. Even after exposure for just 30 minutes, significant changes in collagen—a structural protein involved in tissue organization—were observed in the placentas. The collagen appeared looser and more “broken” compared to the dense, organized collagen of unexposed tissues.

The team also noted that after an hour of exposure, the placentas began producing more human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG), a hormone that peaks in the first trimester and helps maintain the uterine lining. However, research suggests that high levels of this hormone in the second trimester are associated with an increased risk of preeclampsia. The new study suggests that air pollution may be a factor in increasing hCG levels, although this hypothesis requires confirmation.

Meanwhile, Hofbauer cells in the exposed placentas had a “visibly active appearance” and had entered an inflammatory state. In a healthy placenta, these cells typically exhibit an anti-inflammatory state, but in preeclampsia, they typically change their state, the researchers note in their report.

“Of course, this is an artificial environment, and you're exposed for a couple of hours,” Hansson noted. It's conceivable that these harmful effects could be cumulative in full-term pregnancies, he said. However, the placental perfusion system currently can't directly record the effects of such prolonged exposure, and it also only captures full-term placentas, not those at earlier stages of development.

However, it makes sense that “if this happens consistently, it would have clinical significance,” Grigg said.

RELATED STORIES

— Placentas are covered in soot from car exhaust. Could it get onto the fetus?

— How concerned should we be about PFAS, the “forever chemicals”?

— “I've never written about an unfamiliar organ”: The origin of the placenta and how it helped us become human

The results suggest that if the inflammation caused by Hofbauer cells can be suppressed with the drug, it could help prevent one of the factors contributing to preeclampsia in polluted areas, Hansson suggested. However, this idea remains to be tested in clinical trials, and inflammation is not the only hallmark of preeclampsia.

Moreover, according to Grigg, a more effective intervention would be to reduce particulate matter levels in the air. “We should be reducing PM2.5 exposure; further information on this is not needed to justify action,” he said.

Grigg also cautioned that the new findings do not necessarily indicate precautions that individual pregnant women should take.

“I wouldn't say, 'Well, pregnant women need to do something to protect themselves,'” he said. “Pregnant women have enough to do without having to think about how they get around the city.”

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not contain medical advice.

TOPICS Air Pollution

Nicoletta Lanese. Social media navigation. Editor of the “Health” channel.

Nicoletta Lanez is the health editor for Live Science and previously served as a news editor and staff writer for this website. She holds a certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and degrees in neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her work has appeared in The Scientist, Science News, Mercury News, Mongabay, and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among other publications. Based in New York City, she is also an avid dancer and performs in productions by local choreographers.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

A study has found that elective cesarean sections are linked to an increased risk of childhood leukemia: What you need to know

Surprising results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater are formed in the stratosphere.

'Epigenetic memory' may help explain why PCOS often runs in families

Scientists grow mini-amniotic sacs in the lab using stem cells

“We know what to do; we just need to implement it.” Pregnancy in the US is more dangerous than in other rich countries. But we can fix it.

Latest news on fertility, pregnancy, and childbirth

Acne drug Accutane may restore sperm production in infertile men, first study suggests.

Scientists have invented “spermbots” that they pilot through an artificial cervix and uterus.

“I Would Never Let a Robot Carry My Baby”: A Poll on “Pregnancy Robots” Divides Live Science Readers

We finally have an understanding of how the egg supply is built up throughout life in primates.

If “pregnancy robots” were a reality, would you use them?

A $14,000 pregnancy robot from China doesn't exist. But is such technology even possible?

Latest news

The oldest known dinosaur with a domed head has been discovered protruding from a rock in Mongolia's Gobi Desert.

A 'rare' ancestor reveals how giant flightless birds reached distant lands.

'The Sun is slowly waking up': NASA warns that extreme space weather could become even more extreme in the coming decades

Scientists have invented a new sunscreen made from pollen.

An anthropologist claims the hand positions on a 1,300-year-old Mayan altar have a deeper meaning.

A laboratory study shows that even short-term exposure to air pollution can cause inflammation of the placenta.

LATEST ARTICLES

1Even short-term exposure to polluted air can lead to inflammation of the placenta, laboratory studies show.

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com