Certain researchers believe that a mechanism termed “inflammaging” is the root cause of the decline observed in the immune response as people get older. However, a more recent investigation casts doubt on this concept.(Image credit: Westend61 via Getty Images)

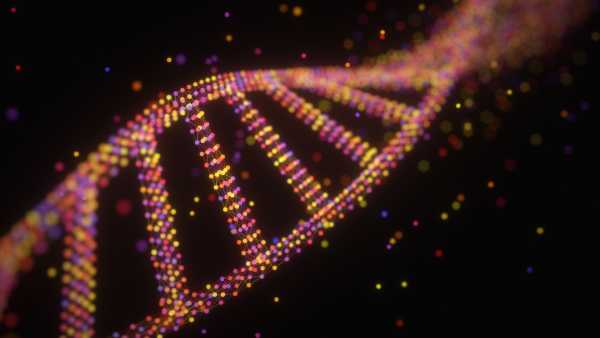

A fresh analysis aids in explaining why specific immunizations, notably those created for COVID-19 and the seasonal flu, have diminished efficacy in senior individuals compared to their younger counterparts — and could potentially challenge established concepts about the aging process.

Conventionally, scientists have connected the lessened reaction to vaccines detected in older individuals to a weakening of the immune defenses that comes with age. A number have indicated that sustained, moderate immune activation — a phenomenon referred to as “inflammaging” — is an underlying factor in this decline.

Conversely, a novel investigation that assessed the immunological systems of both older and younger people revealed no dependable elevations in measurable inflammation as age increased. Instead, the evidence suggests that growing older seems to alter the programming of T cells — critical immune entities that play a role in instructing a subset of white blood cells, known as B cells, to generate antibodies in response to pathogens and inoculations.

You may like

-

Special protection may help human eggs stay fresh as the body ages

-

Vaccines hold tantalizing promise in the fight against dementia

-

‘Aging clocks’ can predict your risk of disease and early death. Here’s what to know.

The results, which were reported on October 29 in the scientific journal Nature, hint that inflammation may not be as vital to the aging mechanism as scholars formerly believed.

“We speculate that inflammation is prompted by an element unrelated to a person’s age,” according to Claire Gustafson, a junior researcher at the Allen Institute for Immunology and one of the main contributors to the investigation, in a written statement.

Alan Cohen, an associate professor in the department of environmental health sciences at Columbia University, specializing in research regarding aging and inflammation, suggested that the new discoveries lend backing to a more detailed perspective on “inflammaging.”

The notion that inflammatory responses amplify as individuals age “could be generally correct among populations in industrialized nations,” Cohen, who was not directly participating in the work, clarified. “Nevertheless, it won’t apply to everyone, nor will it hold across all population groups,” he communicated to Live Science.

Cohen indicated a note of caution that the individuals engaged in the latest investigation were specifically from Palo Alto, California, and Seattle, Washington — both of which are considerably developed regions. Considering that he has identified noteworthy variances in inflammation among adult groups hailing from Italy, Singapore, Bolivia and Malaysia, he cautioned that similar findings may not be consistent across various geographic environments.

“I assuredly would not consider this an absolute confirmation that there are no shifts in inflammation as individuals age,” Cohen expressed. “I would interpret it rather as a demonstration of a group where standard assumptions may not necessarily hold true.”

T cell alterations are not caused by inflammatory processes

With the intention of enhancing the response to vaccines among the elderly, Gustafson and her associates focused on how T cells evolve with age.

You may like

-

Special protection may help human eggs stay fresh as the body ages

-

Vaccines hold tantalizing promise in the fight against dementia

-

‘Aging clocks’ can predict your risk of disease and early death. Here’s what to know.

As a first step, they evaluated younger individuals (between 25 to 35 years old) against an older group (between 55 and 65 years old, or those who the researchers designated as being at the “cusp of aging”). Over the span of a couple of years, the researchers observed 96 healthy participants in these age brackets, obtaining blood specimens from each volunteer on eight to ten separate occasions and keeping track of their immune responses prior to and after their yearly influenza vaccines. Following this, they broadened their inquiry to encompass a second set of 234 individuals, whose ages varied from 40 to beyond 90 years.

To scrutinize the immune system among these categories, the researchers utilized single-cell RNA sequencing, which provided insights into a kind of genetic element identified as RNA inside individual immune cells. RNA reveals which proteins a cell is generating at any given time. The team likewise employed high-dimensional plasma proteomics, which identifies the proteins that circulate within the bloodstream, alongside spectral flow cytometry, a technique used to identify and tally immune cells via their distinct molecular “fingerprints.”

The researchers detected notable contrasts in memory T cells — immune cells that “remember” past occurrences of infection and promote a more immediate bodily response when confronted by an identical pathogen subsequently.

In more elderly people, an increasing quantity of memory T cells move into a state that influences their response to threats — specifically by modulating their connection with B cells. The investigation revealed that B cells are less capable of producing antibodies in reaction to infections or vaccines if memory T cells are not functioning correctly. In contrast, young adults’ memory T cells displayed an ability to respond swiftly and strengthen the anticipated antibody generation.

These shifts in immune function appear to take place irrespective of inflammation and infections induced by latent viruses, which linger within the body following the primary infection stage and may subsequently become dormant, without causing noticeable symptoms. Infections from these kinds of viruses, such as cytomegalovirus (CMV), are frequently attributed to the weakening of the immune system that accompanies age. Nevertheless, the investigation discovered that individuals below 65 who had at some juncture in their lives been subjected to a CMV infection did not exhibit indications of accelerated immune aging or enhanced concentrations of inflammatory proteins.

RELATED STORIES

—Biological aging may not be driven by what we thought

—’If you don’t have inflammation, then you’ll die’: How scientists are reprogramming the body’s natural superpower

—’Aging clocks’ tell you how much ‘older’ you are than your chronological age. How do they work?

Cohen maintains a degree of skepticism regarding the interpretations put forth by the investigation’s authors, drawing attention to the fact that the most significant modifications in the immune system often manifest following the age of 65. “If inflammatory changes are not detected in the comparison between a group aged 25 to 35 and a group aged 55 to 65, does this signify an absence of inflammatory change during aging, or is it due to a lack of sufficient aging within the sample to observe such changes?” he inquired.

The scientists indicated that these discoveries may eventually guide researchers in designing vaccines that account for immune variations linked to age, leading to enhanced protection for older individuals. They propose that their conclusions may assist in formulating approaches to revive immunological functionality in older adults.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

TOPICSvaccines

Clarissa BrincatLive Science Contributor

Clarissa Brincat works as a freelance author, focusing primarily on subjects related to health and medical research. Following her MSc in chemistry, she determined that her preference was to write about, rather than conduct, science. She developed expertise in editing scientific documents during a period as a chemistry copyeditor, subsequently taking on a medical writing position at a healthcare organization. Writing for physicians and experts provides its own fulfillment, yet Clarissa wished to connect with a larger audience, which then guided her toward freelance health and science writing. Her work has also been featured in Medscape, HealthCentral and Medical News Today.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Vaccines hold tantalizing promise in the fight against dementia

Special protection may help human eggs stay fresh as the body ages

‘Minibrains’ reveal secrets of how key brain cells form in the womb

‘Aging clocks’ can predict your risk of disease and early death. Here’s what to know.

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

Latest in Ageing

‘Aging clocks’ can predict your risk of disease and early death. Here’s what to know.

Aging: What happens to the body as it gets older?

Sourse: www.livescience.com