A cast of a juvenile T. rex nicknamed Cleveland next to the skull of a young adult, known as B-rex, on display at the Museum of the Rockies in Bozeman, Montana.

Tyrannosaurus rex wasn’t born the massive beast known for ripping prey to shreds. A paleontologist has found the beast goes through 21 distinct growth stages as it develops from a wee, slender tot to a full-grown, massive dinosaur king. And the two most important stages on its growth chart occurred when T. rex became a teenager and around its 18th birthday.

The study — the most comprehensive to date focused on T. rex growth — also revealed: The male and female skeletons look exactly alike; the controversial Nanotyrannus is not a separate species; and adult T. rex’s size and weight are not predictive of its age.

Paleontologist Thomas Carr spent about three years studying 44 different T. rex skeletons being stored at natural history museums across North America. It was a laborious but rewarding scrutiny of the hypercarnivore, which lived from about 67 million to 65 million years ago, at the end of the Cretaceous period, he said.

“I just love the way these animals look,” Carr, a vertebrate paleontologist and an associate professor of biology at Carthage College in Wisconsin, told Live Science. “I’m in love with their faces. I think they’re beautiful. And I want to understand every little [developmental] change that happens. I want to see through their eyes, if that’s at all possible.”

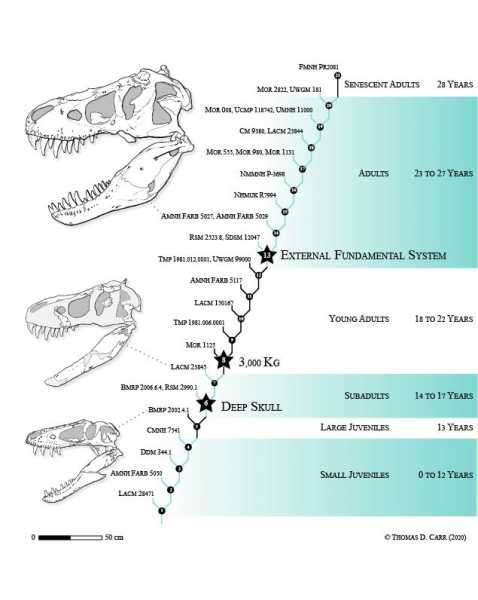

The dinosaurs in the study ranged in age from a 2-year-old at the Natural History Museum of Los Angeles County to the 28-year-old Sue at the Field Museum in Chicago.

Every time Carr examined a different T. rex, he assessed up to 1,850 features on it, such as skull length, chronological age (as determined from the growth rings in certain bones) and the presence of certain bumps on the bones.

Paleontologist Thomas Carr examines the “Tufts-Love” T. rex at the Burke Museum of Natural History and Culture in Seattle, Washington.

After studying the 44 T. rexes, Carr excluded 13 “wildcards” because they didn’t fit in with the rest of the data. But even with 31 T. rexes, “this work is clearly the most massive, time-intensive effort to understand the growth of the tyrant king,” said Lindsay Zanno, head of paleontology at the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences, who wasn’t involved in the study.

For instance, the data revealed that the two most important stages happened when T. rex roared into its teenage years and later, when it lumbered into young adulthood.

The first change happened when T. rex exited its preteen years. Just before turning 13, “when T. rex was young, the skull was very long and low, [with] fairly narrow teeth,” Carr said. “These animals are about 21 feet [6.4 meters] long.” The sleek juveniles “don’t look like adults at all. In fact, juveniles have been mistaken as a different species called Nanotyrannus, but they’re really young rexes,” he said.

Then, sometime between age 13 and 15 (there are no specimens that died at age 14), “everything changes,” Carr said. “In a span of two years, the entire head and jaw deepen, the teeth get thick and basically they now look like T. rexes.”

The second monumental change happened just after that, around the time of their 18th birthday. “That’s when T. rex is heavier than 3 tons [2.7 metric tons]. And that’s important because no other tyrannosaurs are that heavy,” Carr said. “By the time T. rex is between 15 and 18 years old and reaches its giant size — it leaves all other tyrannosaurs in the dust in terms of size.”

This diagram shows the 21 different stages that T. rex went through as it grew from a slender tot into a hulking giant.

It was already known that T. rex outpaced its fellow tyrannosaurs in terms of growth, “achieving colossal size by packing on the pounds faster,” Zanno told Live Science. “We knew that Tyrannosaurus rex had to morph from baby into a bone-crunching behemoth in just around two decades, but until now, we didn’t have a complete understanding of how this transition occurred.”

However, big and heavy T. rexes weren’t necessarily older than less robust adults. “For example, one of the least mature adults [known as Scotty] is also the largest and most massive example of the species,” Carr wrote in the study. His research puts Scotty in the 23 to 27 age bracket, meaning the dinosaur is younger than Sue.

Carr’s data also revealed that T. rex male and female skeletons looked exactly alike, as is true of other dinosaurs. The only known ways to sex a dinosaur are to see if it has eggs inside of it, or to find medullary bone, a special bone tissue found in the long bones of females only when they are pregnant.

Is Nanotyrannus real?

As for the Nanotyrannus controversy, Carr studied the Cleveland skull (the first so-called Nanotyrannus) and the teenage Jane, another Nanotyrannus candidate. Some people think that Nanotyrannus is a type of dwarf tyrannosaur, but many paleontologists think that it’s simply a young T. rex.

According to data gathered on each specimen, these so-called Nanos fit perfectly into the T. rex growth series , Carr said.

“If they were a separate species, they ought to be sharing a branch and they ought to be on a branch separate from the other T. rex, but they aren’t; they’re successive,” Carr said. In addition, Jane is at a transitional stage between the younger Cleveland skull and the older T. rexes, he said.

“It turns out that Jane actually shows the first indications that the skull is starting to get deep. You don’t see that in the Cleveland skull,” Carr said. “So, Jane is actually almost like a missing link between the Cleveland skull — a really slender-snouted juvenile — and the subadults and adults that look like normal rexes.”

These results jibe with those of another study, published in January in the journal Science Advances, which looked at Jane’s bone growth. Jane’s bones showed “features characteristic of actively growing juvenile dinosaurs that had not yet entered an exponential phase of growth,” the researchers wrote in that study, meaning that Jane was a growing T. rex, not a dwarf dinosaur.

Nanotyrannus, however, still needs to be investigated further, said Mark Norell, the chair and Macaulay Curator of Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, who was not involved in the research, but has worked with Carr on other studies.

Even though Norell said he personally agrees that Nanotyrannus is likely a young T. rex, and even though the Cleveland skull and Jane fit into Carr’s T. rex growth series, there are still questions about Nanotyrannus’ anatomy, including the length of its forelimbs and the fact that it has more teeth than adult T. rexes do, he said.

“I don’t think the case is open and shut on that animal yet,” Norell noted.

Not enough rexes?

Norell questioned some of Carr’s other findings, too. That’s because even with 31 T. rexes “the sample [size] is still small, especially when you take into account how poorly preserved the specimens are,” Norell told Live Science.

A better sample size would have included 25 T. rexes for each age group, Norell said. (Granted, that many T. rexes haven’t been found yet, Carr previously told Live Science.) With so few dinosaurs in the study, the assessment that there are 21 growth stages “is a little over-split, especially concerning the sample size,” Norell added. Even the lack of sex differences is suspect: “Because of [the] sample size, I don’t think that you can tell either way,” Norell said.

Carr defended his work, saying that his method to uncover the T. rex’s growth over time “isn’t a statistical test that is dependent upon a high sample size. In fact, the sample size of the specimens in my analysis (31) is at the norm, whereas the amount of data (1,850 characters [per dinosaur]) is extraordinarily high for an analysis of this type.”

For comparison, in another study, this one co-led by Carr, the researchers analyzed 30 species of tyrannosaur and examined “a mere 386 characters,” per specimen to come to the conclusion that T. rex might have been an invasive species from Asia, he said.

If the growth results weren’t truly present in the new analysis, “a growth series wouldn’t have been recovered in the first place,” Carr added.

The new study was published online June 4 in the journal PeerJ.

Sourse: www.livescience.com