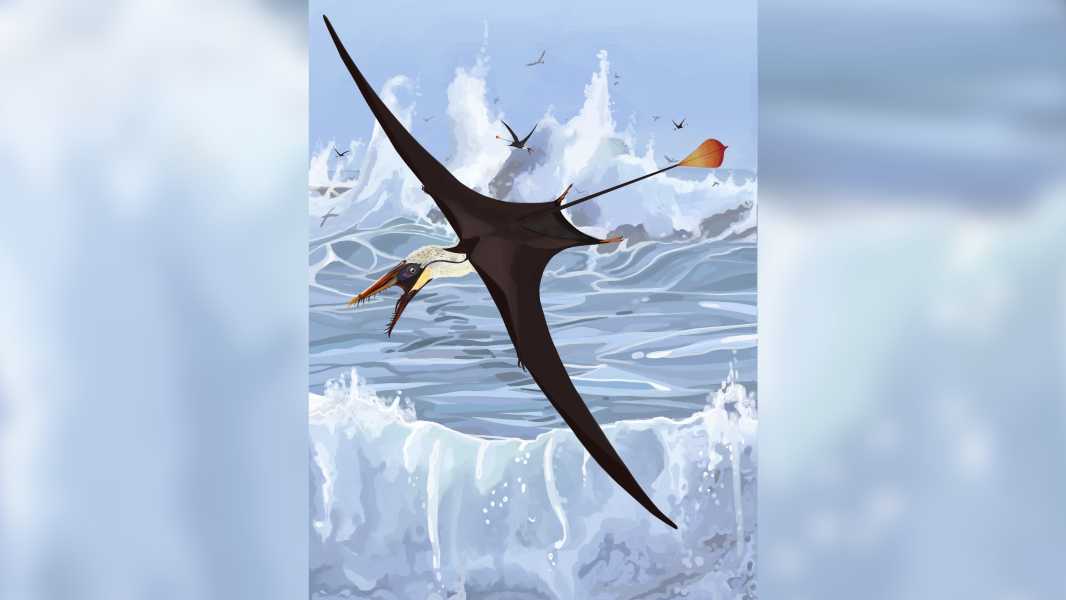

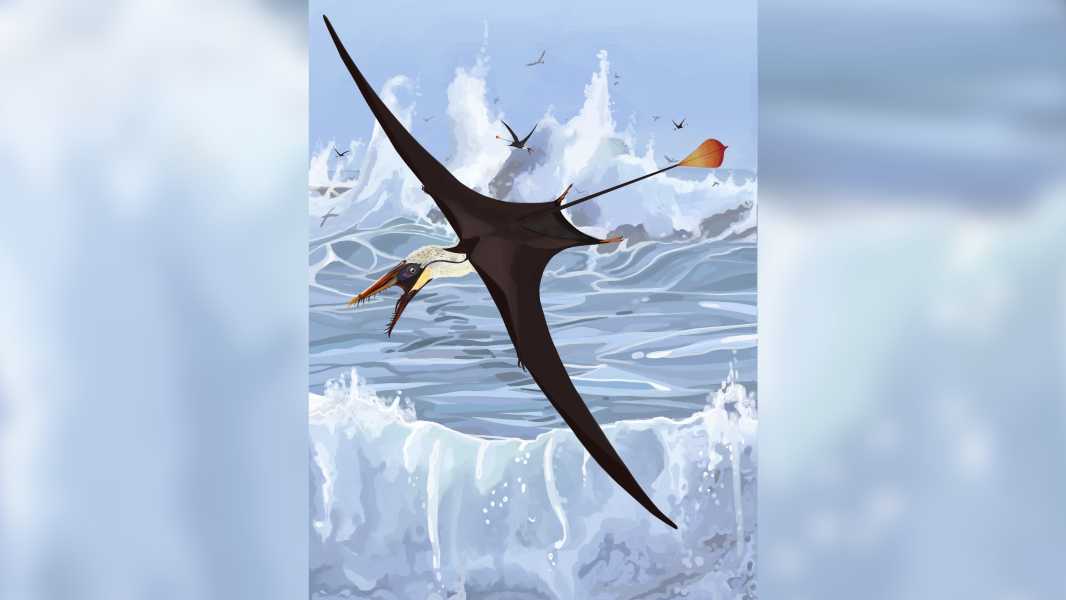

An illustration of an early pterosaur using its tail feathers to fly. (Photo courtesy of Dr. Natalia Yagelskaya)

A new study has found that early pterosaurs began flying during the dinosaur era using a sail-like tension system.

Early pterosaurs—informally known as “pterodactyls”—had long tails with thin, flat flaps of tissue at the ends, known as paddles. These paddles would have made it difficult for them to fly if they were flexible and flapped like a flag, so paleontologists already knew they were rigid, but until now they hadn’t figured out how exactly the paddle maintained its rigidity.

The researchers used powerful lasers to analyze skin and other soft tissue preserved in fossilized pterosaur tails. They found that the blade had intersecting fibers and tubular structures that could support a complex tension system, according to the study.

The team suggests the tension system allowed the blade to function like a sail on a ship, stretching in response to gusts of wind, allowing the creature to control its movement, according to a statement released Jan. 7.

“It always amazes me that, despite the fact that hundreds of millions of years have passed, we can ‘dress’ skin on the bones of animals that we will never see in our lives,” said lead author Natalia Yagelskaya, who was a PhD student at the University of Edinburgh in the UK when she worked on the study and is now a curator at the Lyme Regis Museum in the UK.

Pterosaur flight has a long history that has baffled paleontologists. In the 18th century, fossilized pterosaur wings were mistaken for the flippers of sea creatures, and in the 19th century, for the wings of giant flying marsupials. Today, scientists know that pterosaurs were flying reptiles that flapped their wings like birds and bats.

For the new study, the researchers analyzed more than 100 early pterosaur fossils with an ultraviolet flashlight to identify specimens with exceptionally well-preserved tail lobes. They then applied a laser technique known as laser-assisted fluorescence imaging to these lobes, which created maps of the lobes’ internal structures, according to the study.

Dave Martill, a pterosaur researcher and emeritus professor at the University of Portsmouth who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email that he thought the research was “innovative” and praised the scientists for studying the plumage so carefully.

“It was previously thought to be simply a flap of (probably hardened) skin,” Martill said. “It now appears to be more than that, and its internal structure likely points to a more complex function.”

The study's authors found that the tension system used to maintain the rigidity of the blades during flight also allowed the animal to use it for display purposes, such as attracting a mate.

Loss of tail.

Long-tailed pterosaurs appeared near the end of the Triassic period (251.9–201.3 million years ago), but their tails became shorter over time and were virtually gone by the time pterosaurs died out along with the dinosaurs at the end of the Cretaceous period (145–66 million years ago).

Martill noted that a group of pterosaurs called Pterodactyloidea (from which the name “pterodactyl” comes) significantly shortened their tail lengths during the Jurassic period (201.3 to 145 million years ago), which likely contributed to their improved aerial maneuverability and diversification of the group.

“Typically, long tails make it difficult to fly,” Martill said. “While they look attractive [like a peacock's], they make it difficult to fly.”

Researchers

Sourse: www.livescience.com