The famous Japanese snow macaques are an exception among modern primates. But our distant ancestors often experienced such weather. (Photo: ANDREYGUDKOV/Getty Images)

Most people picture our distant primate ancestors roaming lush tropical forests. But new research suggests they braved the cold.

As an ecologist who has studied chimpanzees and lemurs in the field in Uganda and Madagascar, I am fascinated by the environments that shaped our primate ancestors. These new discoveries challenge long-held assumptions about how and where our kind began.

The question of our own evolution is fundamental to understanding who we are. The same forces that shaped our ancestors shape us and will shape our future.

You may like

-

'It makes no sense to say Homo sapiens had only one origin': How Asia's evolutionary record complicates our knowledge of our species

-

'Huge Surprise': How Some People Left Africa 50,000 Years Ago

-

DNA has an expiration date. But proteins reveal secrets of our ancient ancestors that we never suspected.

Climate has always been a critical factor in determining ecological and evolutionary change: which species survive, which adapt, and which disappear. And as the planet warms, the lessons of the past are more relevant than ever.

The Cold Truth

A new study by Jorge Avaria-Llautureo of the University of Reading and others maps the geographic origins of our primate ancestors and the historical climates in those places. The results are surprising: rather than evolving in warm tropical conditions, as scientists previously thought, early primates appear to have lived in cold, dry regions.

These environmental challenges likely played a critical role in our ancestors adapting, evolving, and spreading to other regions. The study shows that it took millions of years for primates to colonize the tropics. Rising global temperatures do not appear to have accelerated the spread or evolution of primates into new species. However, the rapid transition from dry to wet climates did facilitate evolutionary change.

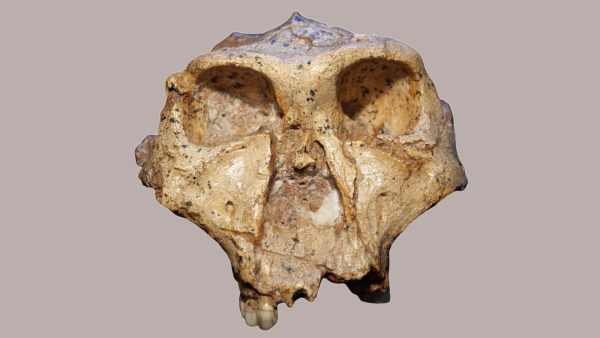

One of the oldest known primates was the Teilhardina, a tiny tree-dweller weighing just 28 grams, similar to the smallest living primate, Madame Berthe's mouse lemur. Because of its small size, the Teilhardina required a high-calorie diet of fruit, chewing gum, and insects.

Fossil evidence suggests that Teijardina differed from other mammals of its time in that it had fingernails rather than claws, which helped it grasp branches and forage for food—a key primate feature that persists to this day. Teijardina evolved about 56 million years ago (about 10 million years after the dinosaurs went extinct), and its species quickly spread from their native North America across Europe and China.

It's easy to see why scientists assumed that primates evolved in warm, humid climates. Most modern primates live in the tropics, and most of their fossils have been found there.

But when the new study used spores and pollen from ancient primate remains to predict climate, they found that these places weren’t tropical at the time. In fact, primates originated in North America (again, contrary to what scientists previously thought, in part because there are no primates in North America today).

Some primates even colonized the Arctic. These early primates may have survived the seasonal cold and resulting food shortages by living a lifestyle much like modern mouse and dwarf lemurs, slowing their metabolisms and even hibernating.

Complex and changing conditions probably favored primates that moved widely in search of food and better habitat. Modern primate species evolved from these highly mobile ancestors. Those that were less mobile left no descendants.

From the past to the future

The study demonstrates the value of studying extinct animals and their habitats. If we want to conserve primate species today, we need to know what threats they face and how they will respond. Understanding the evolutionary response to climate change is critical to preserving primates worldwide and other species beyond.

RELATED STORIES

— What did the last common ancestor of humans and apes look like?

— Look at how drinking chimpanzees share fruits with alcohol. Is this how the tradition of collective drinking began?

— A study conducted on chimpanzees suggests that “contagious” urination may have deep evolutionary roots.

When their habitat disappears, often due to deforestation, primates are unable to move freely. With smaller populations, smaller ranges, and less diverse territories, modern primates lack the genetic diversity to adapt to changing conditions.

But to save the world’s primates, we need more than just knowledge and understanding. We need political action and behavioral change for everyone to combat bushmeat consumption—the primary driver of human primate hunting—and reverse habitat loss and climate change. Otherwise, all primates, including us, will be at risk of extinction.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jason Gilchrist, Edinburgh Napier University

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be prompted to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

'It makes no sense to say Homo sapiens had only one origin': How Asia's evolutionary record complicates our knowledge of our species

'Huge Surprise': How Some People Left Africa 50,000 Years Ago

DNA has an expiration date. But proteins reveal secrets of our ancient ancestors that we never suspected.

Newly discovered fossils show that birds have been nesting above the Arctic Circle for nearly 73 million years.

2.2-million-year-old teeth reveal secrets of human ancestors found in South African cave

Strange pits on teeth of 'hobbits' and other ancient humans may reveal hidden connections in our family tree. Latest news on land mammals

Texas cougar genes are saving Florida cougars from extinction—for now.

What is the difference between a llama and an alpaca?

Why do cats and dogs eat grass?

Why do cats hate water?

The return of wolves to Yellowstone has led to a surge in aspen growth not seen in 80 years.

Why Do Cats Love Concrete Slabs? Latest Opinion

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

You may not be allergic to penicillin. Here's how to find out if you are.

Vaccines show promise in fight against dementia

COVID-19 vaccines for children in limbo due to conflicting federal recommendations

Data from the North Sea shows that “rogue waves” can reach heights of 65 feet, but they are not “anomalous events”.

How an AI assistant is changing teen behavior in surprising and sinister ways LATEST ARTICLES

1Unexpected results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater originate in the stratosphere.

Live Science is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web Notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-crosspost,exclude-from-syndication,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com