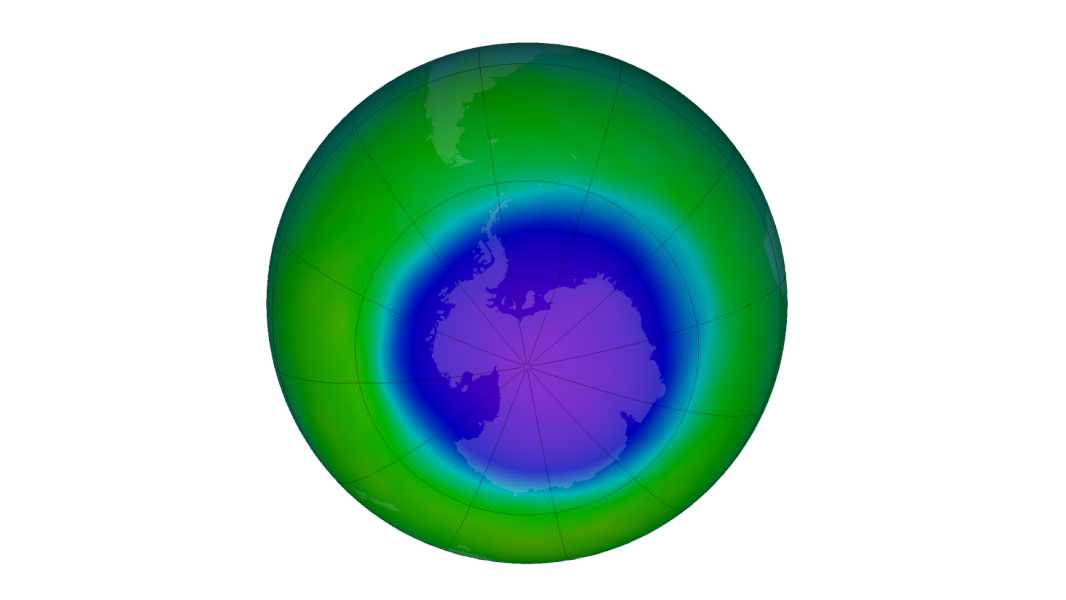

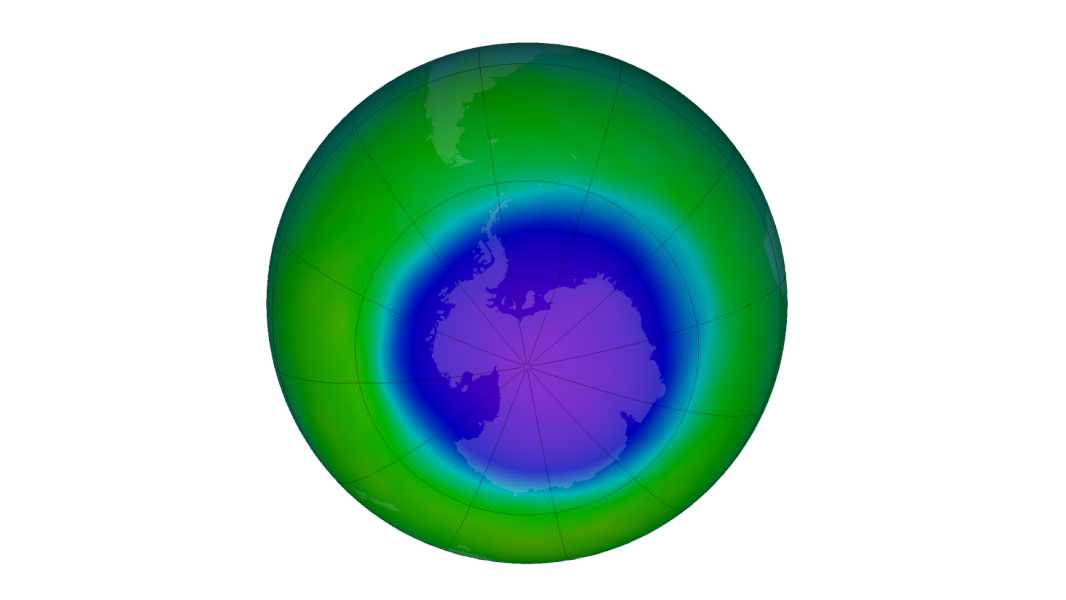

False-color image of monthly average total ozone over the Antarctic pole in October 2022. Blue and purple colors represent areas with the lowest ozone. (Image credit: NASA)

The ozone hole that forms annually over Antarctica has grown for the third year in a row. At nearly 10 million square miles (26.4 million square kilometers), it is the largest since 2015.

However, despite this increase, scientists say the overall size of the hole continues to show a decreasing trend.

“All the evidence suggests that the ozone layer is recovering,” Paul Newman, chief scientist at NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center, told The Associated Press.

Ozone, a molecule made up of three oxygen atoms, makes up only a small portion of our atmosphere, but it has a significant impact on our planet. Like a blanket around the globe, this layer absorbs the sun's most dangerous ultraviolet (UV) radiation, protecting life on Earth. Ozone forms in the stratosphere, between 9 and 18 miles (14.5 and 29 kilometers) above the Earth's surface. It is formed when UV radiation splits two-atom oxygen molecules (O2); two free oxygen atoms then combine with each oxygen molecule to create a three-atom oxygen molecule.

Scientists first detected the thinning of the ozone layer over Antarctica in the early 1980s. Although ozone is naturally formed and destroyed in the stratosphere, human pollution is destroying it faster than it can regenerate. In particular, industrial processes that use chlorine or bromine, such as refrigeration and air conditioning, destroy ozone at an alarming rate. In the stratosphere, chlorine molecules react with ozone to form one molecule of chlorine monoxide (made up of a chlorine atom and an oxygen atom) and one molecule of O2. The chlorine monoxide molecule then breaks apart, releasing that chlorine atom to react with more ozone. According to the Environmental Protection Agency, one chlorine atom can destroy 100,000 ozone molecules before it is removed from the atmosphere.

Chlorofluorocarbons used in refrigeration and air conditioning remain in the atmosphere for long periods of time – some for more than six months – meaning that chlorine and other substances in these compounds can damage the ozone layer.

The ozone hole was first recorded in the early 1980s and peaked in 2006, according to NASA. This year's hole, which peaked on Oct. 5, was the largest recorded since 2015. But scientists aren't too worried about the situation.

“The overall trend is improving. This year it's been a little bit worse because the temperatures have been cooler than normal,” Newman told the AP.

The cold stratosphere is the perfect environment for chemicals like chlorine to destroy ozone. During the Antarctic winter, the stratosphere becomes cold enough for clouds to form. The ice crystals that make up these clouds provide a surface on which chlorine can react with ozone. As spring arrives in September, ultraviolet rays activate these reactions. As summer peaks, the stratosphere warms, causing clouds to evaporate, eliminating the surface for the chemical reactions that destroy ozone.

Global initiatives such as the Montreal Protocol, which regulates the production and consumption of substances that deplete the ozone layer, have helped the ozone layer recover. And while the ozone hole has grown in size this year, scientists generally believe it is shrinking.

Previously

Sourse: www.livescience.com