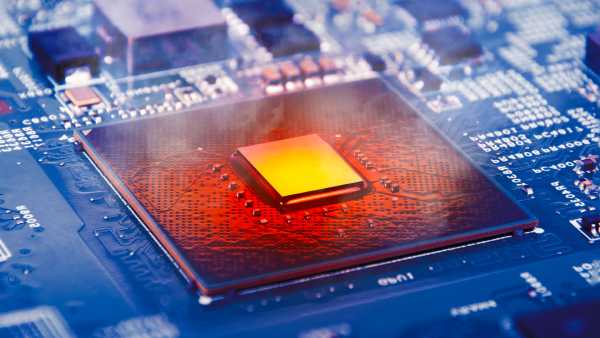

While neural nets possess the capability to construct visuals, it comes at a steep power expense relative to systems grounded in probabilistic computation. (Image credit: Eugene Mymrin via Getty Images)

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterLive ScienceGet the Live Science Newsletter

Get the most captivating global discoveries conveyed promptly to your inbox.

Become a Member in Seconds

Obtain prompt entrance to unique member facets.

Contact me with news and offers from other Future brandsReceive email from us on behalf of our trusted partners or sponsorsBy submitting your information you agree to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and are aged 16 or over.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter enrollment has been completed successfully.

Want to add more newsletters?

Delivered DailyDaily Newsletter

Subscribe for the newest revelations, cutting-edge investigations, and enthralling innovations that bear upon you and the greater world specifically to your inbox.

Signup +

Once a weekLife’s Little Mysteries

Satiate your inquisitiveness through an exclusive riddle each week, resolved by science and transported straight to your inbox prior to being viewed elsewhere.

Signup +

Once a weekHow It Works

Join our complimentary science & technology periodical for your regular portion of captivating articles, brief assessments, striking depictions, and more

Signup +

Delivered dailySpace.com Newsletter

Breaking space bulletins, the most recent notifications regarding rocket dispatches, stargazing occurrences, plus additional features!

Signup +

Once a monthWatch This Space

Join our monthly entertainment periodical to remain abreast of all our reporting on the newest sci-fi and cosmic films, television series, games and publications.

Signup +

Once a weekNight Sky This Week

Uncover this week’s unmissable celestial happenings, lunar periods, and breathtaking star pictures. Subscribe to our stargazing periodical and delve into the cosmos alongside us!

Signup +Join the club

Secure complete admittance to exceptional writings, distinct elements and a developing directory of member reimbursements.

Explore An account already exists for this email address, please log in.Subscribe to our newsletter

Researchers have engineered a “thermodynamic computer” with the aptitude to yield images stemming from unpredictable disturbances in data, namely, noise. In undertaking this, they have replicated the generative artificial intelligence (AI) prowess of neural networks — assemblies of machine learning calculations patterned after the brain.

At temperatures surpassing absolute zero, the environment is inundated with variations in energy designated as thermal noise, which surfaces in atoms and molecules oscillating, atomic-level shifts in direction regarding the quantum attribute that provides magnetism, and akin occurrences.

Contemporary AI infrastructures — paralleling the majority of existing computer mechanisms — generate pictures utilizing computer microchips wherein the energy demanded to alter bits eclipses the quantity of energy present within the spontaneous oscillations of thermal noise, therefore rendering the noise inconsequential.

You may like

-

Scientists assert that by leveraging a novel ‘probabilistic computing’ model, AI chips can drastically diminish power consumption

-

MIT’s breakthrough in chip arrangement promises to reduce energy utilization within power-intensive AI operations

-

MIT designs a computational component that harnesses dissipated heat ‘as an informational resource’

However, a pioneering “generative thermodynamic computer” functions by capitalizing on the system’s intrinsic noise instead of attempting to circumvent it, thus permitting it to execute computing tasks with substantially less energy than typical AI systems necessitate. The scientists detailed their discoveries within a recent paper featured on Jan. 20 in the journal Physical Review Letters.

Stephen Whitelam, a scientific member at the Molecular Foundry situated at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and principal author of the new study, offered an allegory involving boats at sea. Within this scenario, waves serve as the analog to thermal noise, while conventional computing can be compared to an ocean liner that “simply proceeds unperturbed as if oblivious — exceedingly efficient, albeit excessively costly,” as he described.

Conversely, if one were to diminish the energy footprint of conventional computing to an extent comparable to thermal noise, it would resemble attempting to navigate a small boat equipped with a minor engine across the sea. “It becomes vastly more intricate,” he conveyed to Live Science, emphasizing that harnessing the inherent noise within thermodynamic computing could be advantageous, similar to “a surfer leveraging the force of a wave.”

Conventional computing relies on precise binary bit representations — 1s and 0s. Nevertheless, a surge in research conducted over the preceding decade has underscored the concept that increased efficacy per resource can be achieved concerning elements such as electricity consumption for task completion by employing value probabilities as an alternative.

The enhancements in efficiency become notably evident when addressing specific problem types classified as “optimization” dilemmas, wherein the goal involves maximizing output while minimizing input — for example, delivering mail to the maximum number of residences while covering the minimum distance on foot. Thermodynamic computation can be regarded as a form of probabilistic computing that employs the spontaneous variations arising from thermal noise to facilitate computation.

Image generation with thermodynamic computing

Researchers affiliated with Normal Computing Corporation situated in New York, who were not directly engaged in this particular image generation effort, have engineered a construct resembling a thermodynamic computer, consisting of a circuit network linked by ancillary circuits, all operating at minimal energies congruent with thermal noise. The circuits responsible for establishing connections could then be programmed to either reinforce or weaken the association they forge among the circuits they connect — referred to as the “node” circuits.

The application of any form of voltage to the system would trigger a collection of voltages at various nodes, allocating values that would eventually subside as the applied voltage was withdrawn, and the circuits reverted to equilibrium.

You may like

-

MIT’s breakthrough in chip arrangement promises to reduce energy utilization within power-intensive AI operations

-

MIT designs a computational component that harnesses dissipated heat ‘as an informational resource’

-

‘Putting the servers in orbit is a stupid idea’: Could data centers in space help avoid an AI energy crisis? Experts are torn.

Even when the circuits achieved equilibrium, the inherent noise caused the nodal values to fluctuate in a predictable fashion, dictated by the programmed intensities of the interconnections, known as coupling strengths. Hence, the coupling intensities could be arranged in such a manner that they essentially posed a query that the ensuing equilibrium variations would resolve. The researchers at Normal Computing demonstrated their ability to configure coupling intensities such that the concurrent equilibrium nodal variations were capable of resolving linear algebra.

Although managing these interconnections presents a degree of influence over the specific inquiry addressed by the equilibrium fluctuations in nodal values, it lacks the capacity to alter the inquiry type. Whitelam questioned whether shifting from thermal equilibrium could assist researchers in conceiving a computer adept at resolving fundamentally varied types of inquiries, in addition to offering enhanced practicality given the potential duration required to attain equilibrium.

While contemplating the categories of calculations potentially rendered feasible by moving away from equilibrium, Whitelam recollected research from around the mid-2010s, which indicated that by incorporating noise into an image until no vestige of the original remained, a neural network could be trained to reverse this process and thus reacquire the image. When trained on a spectrum of such disappearing images, the neural network gained the capability to produce an array of images from a random noise baseline, encompassing images extending beyond its training library. These diffusion models struck Whitelam as “a natural jumping-off point” for a thermodynamic computer, with diffusion per se being a statistical mechanism rooted in thermodynamics.

While conventional computing procedures reduce noise to insignificant magnitudes, Whitelam recognized that numerous algorithms employed to train neural networks incorporate noise again. “Wouldn’t that be considerably more instinctive within a thermodynamic framework where noise is obtained without effort?” he inferred from a conference transcript.

Borrowing from age-old principles

The manner in which entities evolve under the sway of notable noise can be determined utilizing the Langevin equation, which dates back to 1908. Manipulating this equation allows for the computation of probabilities for each phase in the process of an image becoming obscured by noise. Essentially, it yields the likelihood of a pixel shifting to an incorrect color as an image undergoes thermal noise.

Subsequently, it becomes feasible to calculate the requisite coupling strengths — for instance, circuit connection intensities — to invert the process, progressively eliminating noise. This in turn creates an image — a capability Whitelam substantiated within a numerical emulation derived from an image repository encompassing “0,” “1,” and “2.” The resultant image may correspond to one contained within the original training database or represent a form of conjecture, and incidental imperfections in the training procedure can potentially spawn novel images absent from the original dataset.

Ramy Shelbaya, CEO of Quantum Dice, a company producing quantum random number generators, who did not partake in the study, characterized the findings as “important”. He referenced specific domains where traditional methodologies are increasingly struggling to fulfill escalating demands for progressively potent models. Shelbaya’s enterprise fabricates a species of probabilistic computing hardware leveraging quantum-derived random numbers, and he therefore perceived it “encouraging to observe the consistently amplifying fascination with probabilistic computing and its intricately related computing models.”

RELATED STORIES

—Scientists assert that by leveraging a novel ‘probabilistic computing’ model, AI chips can drastically diminish power consumption

—Scientists devise the planet’s initial microwave-powered computer chip — delivering superior speed while consuming less energy compared to conventional CPUs

—Scientists pack an entire computer inside a singular clothing fiber — enabling even its passage through your washing appliance

He also highlighted a prospective advantage transcending energy conservation: “This publication additionally illustrates the potential of physics-stimulated methodologies to render an explicit fundamental interpretation to an arena where “black-box” models have prevailed, delivering indispensable perspectives into the learning mechanism,” he conveyed to Live Science through email.

Concerning generative AI, the recovery of three memorized numerals from noise might appear marginally elementary. Nevertheless, Whitelam accentuated that the notion of thermodynamic computing remains in its embryonic stages.

“Considering the development of machine learning and its eventual scaling to more substantial, spectacular endeavors,” he stated, “I’m intrigued to discover whether thermodynamic hardware, even as a conceptual construct, can undergo scaling in an analogous fashion.”

Article Sources

Whitelam, S. (2025). Generative Thermodynamic Computing. Physical Review Letters, 136(3), 037101. https://doi.org/10.1103/kwyy-1xln

Anna DemmingLive Science Contributor

Anna Demming is a self-employed science columnist and editor. She possesses a PhD from King’s College London in physics, concentrating on nanophotonics and light interaction with minuscule entities. She commenced her publication career with Nature Publishing Group in Tokyo in 2006. Subsequently, she served as an editor for Physics World and New Scientist. Her contributions as a freelance author encompass The Guardian, New Scientist, Chemistry World, and Physics World, among others. Her scientific passions are widespread, with particular emphasis on materials science and physics, notably quantum physics and condensed matter.

View More

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

MIT’s breakthrough in chip arrangement promises to reduce energy utilization within power-intensive AI operations

MIT designs a computational component that harnesses dissipated heat ‘as an informational resource’

&