More women in the United States die during or shortly after childbirth than in many developed countries. (Image credit: Marilyn Perkins photo collage)

Jordyn Albright's pregnancy and birth were complicated from the start. Her pregnancy was high-risk due to in vitro fertilization (IVF) and high blood pressure during pregnancy. She was induced three weeks early and labor lasted 60 hours.

With her son in her arms, the worst should have been over. But moments later, the doctor discovered that the placenta was stuck to the wall of her uterus. Hospital staff surrounded her, trying to manually remove the placenta — “a terribly painful experience,” said Albright, 32. She continued to bleed.

Just minutes after giving birth, Albright collapsed from blood loss. She didn’t hear her care team call for emergency response—the maternity ward alarm that sends a team of doctors and nurses to the room. That team saved Albright’s life by giving her four pints of blood (she later needed two more) and rushing her to the emergency room to have the retained placenta removed.

You may like

-

8 Children Saved From Potentially Deadly Inherited Diseases Thanks to New IVF Study Using 'Mitochondrial Donation'

-

'These decisions were completely reckless': Cutting funding for mRNA vaccines will make America more vulnerable to pandemics

-

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

Jordyn Albright in the hospital with her son and husband just after giving birth. Moments later, she began bleeding, and doctors transfused her with six pints of blood to save her life.

That harrowing experience was followed by several traumatic days in the intensive care unit (NICU) and separation from her newborn. That was compounded by weeks spent in the neonatal intensive care unit, where she developed a rare bacterial infection after birth. But Albright and her husband, Jeffrey Albright, credit their medical team with saving both mother and baby.

“It could have been a lot worse,” Jeffrey Albright, 32, told Live Science. “It could have been worse, no matter how you look at it.”

For too many families, the situation is even worse. The U.S. has a higher rate of death during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period than comparable rich countries. It’s a problem of health care inequality, access to care, and how individual hospitals handle emergencies — problems that experts say could be exacerbated by recent U.S. policy decisions.

Despite the grim figures, there is hope. Evidence suggests that most of these deaths are preventable, and that some relatively simple measures can reduce maternal mortality rates. These include better prenatal monitoring to prevent emergencies, as well as better training for hospital staff to respond to emergencies.

“We know what to do,” said Jean Conrey, a former president of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics. “We just need to implement it.”

Causes of maternal mortality

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) defines a maternal death as the death of a patient during pregnancy or within 42 days of delivery from any cause related to or aggravated by pregnancy. For example, a mother who dies in a car accident during pregnancy does not count, but a mother who dies of a preexisting heart condition that is worsened by pregnancy does count.

While maternal mortality is rare in the United States, its rate is higher than in other wealthy countries. In 2024, there will be 19 maternal deaths for every 100,000 live births, according to preliminary data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), compared with 8.4 in Canada, 8.8 in South Korea, 5.5 in the United Kingdom and zero in Norway, according to the Commonwealth Fund, a health policy foundation.

The United States has long stood out among its wealthy neighbors in maternal mortality rates, even though the country spends about twice as much per capita on health care as other large, wealthy countries, according to the Peterson Center for Public Health and the health policy research organization KFF.

“We’re very low on the global stage,” said Dr. Monique Rainford, an associate professor of obstetrics, gynecology, and reproductive sciences at the Yale School of Medicine and the CEO and co-founder of Enrich Health, a startup that aims to provide evidence-based prenatal care.

About half of maternal deaths in the U.S. occur the day after birth, and about a third occur during pregnancy, according to the Commonwealth Fund. A third of pregnancy deaths are due to stroke and heart disease, while emergencies such as hemorrhage are the leading cause of death during childbirth, according to the March of Dimes. Bleeding, high blood pressure (including pregnancy-related conditions such as preeclampsia, a life-threatening, persistent high blood pressure that can develop during pregnancy or within six weeks after delivery), infections, and cardiomyopathy (weakening of the heart muscle) are the leading causes of death after childbirth.

“Our findings show that cardiovascular disease is indeed on the rise,” Conrey told Live Science.

While the United States has high rates of some diseases that increase the risk of complications during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, such as obesity, other countries with high rates of these risk factors have much lower death rates than the United States.

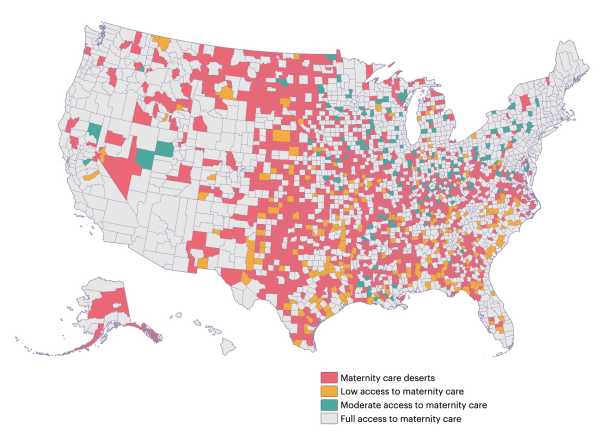

Desertion of maternity hospitals

One factor in the comparatively poor outcomes in the U.S. is that many women live in “birth deserts” — areas without a single hospital offering maternity services or neonatal specialists. According to the March of Dimes, 35 percent of U.S. counties are considered “birth deserts.”

As of 2022, 52% of rural hospitals did not offer obstetric care, and the problem has gotten worse since then. According to a study published in JAMA in 2024, 238 rural hospitals stopped offering obstetric care between 2010 and 2022, and only 26 rural hospitals added obstetric care to their services during that period. (Over the same period, 299 urban hospitals stopped offering obstetric care, but 112 added new services.)

Additionally, a 2021 study of maternity hospital closures in New Jersey found that women experienced higher rates of maternal morbidity (a measure of serious and life-threatening complications related to pregnancy and childbirth) if they gave birth after an obstetrics unit at a nearby hospital closed.

A map showing the location of maternity hospitals in the United States in 2024.

Lack of obstetric care is a serious problem in rural areas, but it is not unique to them. About 35% of urban hospitals lack obstetric care. In addition, other problems with access to care can make it difficult for women to access antenatal care, where problems can be identified and addressed early.

Even in densely populated Chicago, “if your Medicaid provider is out of network, you often have to take public transportation in terrible weather, often with other children, to get preventive care,” says Star August Ali, a certified professional midwife and executive director and founder of the Black Midwifery Collective in Chicago, which aims to train and support Black midwives.

Impending cuts

The Medicaid funding cuts under the Big Beautiful Bill Act, which went into effect in July, could have a major impact on maternal mortality rates. According to KFF, the cuts are expected to hit rural hospitals hard, as 144 rural maternity units are likely to close.

About 41% of births in the U.S. are covered by Medicaid. It’s unclear how the funding cuts will affect pregnant women’s health coverage, but without the program, they may not have access to treatment and care that could prevent some life-threatening emergencies.

The impact of these policies is uneven. Medicaid covers about 28% of births to white mothers, 64% of births to black mothers, and 67% of births to American Indian or Alaska Native mothers. Younger women are also more likely to get health care through Medicaid than through private insurance: Nearly 79% of births to mothers under age 20 are covered by the government program.

Ali told Live Science that if fewer pregnant women are enrolled in the program, “we'll see a huge increase in emergency room use and a huge reduction in preventive care and early diagnosis” during pregnancy.

Racial differences

The same groups that stand to lose the most coverage from Medicaid cuts are also at higher risk for adverse maternal and infant outcomes. Black and Native American women are two to three times more likely to die during pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period than white women, according to KFF.

Some of this inequality is due to access to care and lower quality of care for people of color. A 2025 study of more than 3,000 hospitals found lower staffing levels and higher death rates at hospitals serving predominantly Black patients compared to hospitals with a lower proportion of Black patients. A 2021 study of maternity unit closures also found that severe maternal morbidity was higher at hospitals serving a high proportion of Black patients.

Research also shows that American Indian and Alaska Native patients face significant gaps in health insurance coverage that can prevent them from accessing vital preventive care.

Racial bias on the part of health care providers may also play a role. A 2017 review of research on doctor-patient communication found that black patients had “poorer communication, information provision, patient engagement, and involvement in decision making” than white patients. This can lead to mistrust between doctor and patient, which impacts clinical decision making, the researchers write. For example, a doctor may perceive a patient as less engaged and not provide important health care recommendations.

Preventable deaths

Despite the overall challenges of the health system, evidence suggests that there are opportunities to prevent a large number of maternal deaths.

“Maternal mortality is an indicator of the health of your country.”

Andrea Creanga, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health

A 2024 study published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology analyzed deaths in 42 states and found that more than 90% of deaths from preeclampsia and eclampsia in the U.S. were preventable. More than 80% of deaths from bleeding and cardiovascular disease were also preventable, and about 70% of deaths from infections were preventable. Deaths from stroke or amniotic fluid embolism, an emergency in which amniotic fluid leaks into the mother’s bloodstream, were harder to prevent, but even then, 40% of deaths were preventable.

The study found that the proportion of deaths that could be prevented through immediate improvements in health care varied widely across states, from 45% to 100%.

“The key finding is this variability,” said study author Dr. Andrea Creanga, a public health researcher at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Such variability is actually encouraging, experts say, because it shows there are clear steps that governments, hospitals and service providers can take to reduce maternal mortality.

Learning from every death

The first step in preventing these deaths is to thoroughly investigate each death, Rainford said.

States that have studied these deaths and used what they learned to take concerted action to reduce maternal mortality have seen success. For example, California’s long-running Maternal Quality Care Collaborative has seen maternal mortality rates decline dramatically in the decade since it began in 2006, putting the state on par with Canada.

Working together helps investigate the causes of individual deaths and identify preventable factors. “It changes everything,” Conrey said.

But current policies and political decisions can hinder efforts to learn from past experiences. After the investigative news organization ProPublica reported on a spate of preventable maternal deaths in Texas and Georgia likely caused by hospitals delaying care out of fears of prosecution under the state’s strict abortion laws, Georgia abruptly fired the entire membership of its maternal mortality committee. The state has not disclosed who currently serves on the committee. The board in Idaho, which also has a strict abortion ban, was disbanded by state lawmakers in 2023 and reinstated in 2024, leading to gaps in its analysis and changes to its methodology. The Texas committee skipped analyzing deaths in 2022 and 2023, two years after the Supreme Court overturned Roe v. Wade and allowed the state to pass laws restricting nearly all abortions.

Lack of transparency in abortion policy is an obstacle to reducing maternal mortality.

Standardization of care

Developing and implementing standards of care is another way to reduce mortality rates. For example, after the California Organization for Quality of Care at Birth conducted a detailed analysis of maternal deaths, a clear pattern emerged: too many women were dying from postpartum hemorrhage, one of the most common causes of maternal death.

So they provided hospitals with emergency response toolkits, including standardized drills, training, and instructions on how to create a “crash cart” with supplies to help with postpartum hemorrhage.

Conrey noted that the same concept of standardized care could be extended to conditions beyond bleeding. For example, the Collaborative will soon release guidance on better recognizing sepsis, a life-threatening infection that can occur during or after childbirth.

Better monitoring of the mother and child before labor also is needed. Over time, the immediate causes of death shift from rapidly developing emergencies, such as bleeding, to chronic conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, Creanga noted.

This highlights the importance of regular monitoring of pregnant women and increased surveillance for those at risk. For example, Johns Hopkins University has launched an initiative called the Maryland Maternal Health Innovations (MDMOM) program, which includes home blood pressure monitoring using telemedicine technology for pregnant women with high blood pressure. This can help identify patients whose health is deteriorating before an emergency occurs. (The Preeclampsia Foundation offers a similar program nationwide.)

Creanga and her colleagues are also working to raise awareness among health care providers and community groups about warning signs of high-risk pregnancies. The goal, Creanga says, is to provide tools for patients and their families and to bring the U.S. into line with countries like Norway, where maternal mortality is extremely rare.

“Maternal mortality is a measure of the health of your country,” she said. “It may be the most important measure.”

TOPICS United States

Stephanie Pappas, Social Link Navigator, Live Science Contributor

Stephanie Pappas is a freelance writer for Live Science, covering topics ranging from geoscience and archaeology to the human brain and behavior. Previously a senior writer for Live Science, she now works as a freelance writer in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie earned a bachelor’s degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be prompted to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

8 Children Saved From Potentially Deadly Inherited Diseases Thanks to New IVF Study Using 'Mitochondrial Donation'

'These decisions were completely reckless': Cutting funding for mRNA vaccines will make America more vulnerable to pandemics

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

The incidence of some early-stage cancers is increasing. Why?

Study Finds Elective C-Section Linked to Increased Risk of Childhood Leukemia: What You Need to Know

U.S. officials fear Trump's NASA budget plan will make it harder to track dangerous asteroids. Latest news on fertility, pregnancy and childbirth

How does the tubal ligation procedure work?

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

Incredible, first-of-its-kind video showing the implantation of a human embryo in real time.

How does the postcoital pill work?

Male birth control pill passes preliminary safety tests, further trials underway

Sperm selection is 'entirely dependent on the egg' – so why does the 'sperm race' myth persist? Latest news

Man's preference for 'soft' bacon may have caused his brain to become infected with worms

Japan's supervolcanic “hell” caldera is home to 17 different volcanoes.

Which Roman emperor reigned the longest?

Science News This Week: Black Holes Galore and Blue Whales That Still Sing

'It makes no sense to say Homo sapiens had only one origin': How Asia's evolutionary record complicates our knowledge of our species

Giant 'X' symbol appears over Chile as two intersecting celestial beams of light: Space Photo of the Week LATEST ARTICLES

1Unexpected results show that toxic chemicals polluting groundwater originate in the stratosphere.

Live Science is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web Notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-feature,no-in-article-video,serversidehawk,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com