At the beginning of September 1812, the retreating Russian army was approaching Moscow, and Kutuzov could no longer postpone the general battle, although he was not completely confident of its success. On September 4, he wrote to the Emperor: “The position in which I stopped at the village of Borodino, 12 miles ahead of Mozhaisk, is one of the best that can be found only in flat places. It is desirable that the enemy attack us in this position, then I have great hope for victory.”

Despite certain shortcomings (the position was considered unsuccessful by many participants in the battle, including Pyotr Bagration and Alexei Ermolov), it allowed them to confidently resist the attack of Napoleon's troops. The Russian position occupied approximately 8 kilometers along the front and blocked both Smolensk roads leading to Moscow, with its right flank resting on the Moskva River near the village of Maslovo, and its left flank on the Utitsky Forest.

The right flank and the center of the position were occupied by the 1st Army of Barclay de Tolly. This wing of the Russian troops was covered from the front by the steep banks of the Kolocha River, and had systems of field fortifications on the flanks. The most vulnerable left flank, based on the Semenovsky fleches, was defended by the 2nd Army of Bagration. Behind the flank of the 2nd Army, in the area of the village of Utitsa, was the infantry corps of General Nikolai Tuchkov, a Cossack detachment, and detachments of the Moscow and Smolensk militias. This group, like the general reserve, reported directly to Kutuzov.

In total, the Russian troops numbered approximately 155 thousand people, of which almost 30 thousand were militiamen and 15 thousand poorly trained recruits, and had 640 guns. Napoleon's army, which had been significantly thinned by this time, had about 135 thousand people with 587 guns. The French surpassed the Russian army in the number of regular cavalry.

On the morning of September 5, the French advance guards approached the Borodino field. The Russian positions were not yet equipped, and Kutuzov decided to hold off the enemy near the village of Shevardino, where a redoubt with 12 guns had been equipped the day before. The redoubt prevented the French army from deploying its forces, and Napoleon ordered it to be taken. The defense of the redoubt was led by General Andrei Gorchakov. He had 12,000 men and 36 guns at his disposal.

The French attacks were one after another broken by the courage of the defenders of the redoubt, which repeatedly changed hands. The battle continued until late at night. The Russians not only did not give up their position, but also took prisoners and guns. The Shevardino battle allowed Kutuzov to gain time to equip his positions and determine the probable direction of the enemy's main attack.

On the morning of September 7, the French Emperor addressed his army with the proclamation: “Soldiers! Here is the battle you so desired! Victory depends on you; we need it; it will give us abundant supplies, good winter quarters and a speedy return to our homeland. Let them say of you: “He was in this great battle near Moscow.”

Kutuzov did not address the army with appeals; they were simply not needed. On the night before the battle, a religious procession with the icon of the Smolensk Mother of God passed along the front of the units taking up their positions. An eyewitness of these events, Fyodor Glinka, recalled: “Of its own accord, at the behest of its heart, the 100,000-strong army fell to its knees and bowed its forehead to the ground, which it was ready to satiate with its blood.”

When the sun's rays broke through the morning fog, Napoleon, who loved beautiful phrases, exclaimed: “Here it is, the sun of Austerlitz!” The Emperor was mistaken, the Russian sun was rising over the battlefield and it illuminated the Russian land for which Russian soldiers were ready to give their lives. And they gave them. And this field became for us for centuries the “Field of Military Glory”.

The Battle of Borodino (in foreign sources, the “Battle of Moscow” – bataille de Moskova) began with a powerful artillery barrage and a diversionary attack on the right flank. This demonstrative attack, according to Napoleon's plan, was supposed to divert attention from the direction of the main attack. The honor of being the first to start the battle fell to Delzon's division, which captured the village of Borodino with a surprise attack. The commander of the Guards Brigade, Karl Bystrom, organized a counterattack, during which one of the rangers captured a French officer. The prisoner was delivered to Kutuzov, who awarded the distinguished soldier the St. George Cross. This was the first award in the Battle of Borodino.

Using their numerical superiority, the French had consolidated their position in the village of Borodino by 6 a.m. and had even captured the bridge over the Kolocha River, but were thrown back across the river by a counterattack by the rangers. The first French general, L. Plosonne, died in this battle, opening a long series of losses for the French generals. The French set up a battery of 38 cannons south of the village of Borodino and began shelling the center of the Russian positions. They made no further attempts to attack in this direction.

At the same time, the corps of Józef Poniatowski, advancing along the Old Smolensk Road, attacked Russian positions near the village of Utica. The Polish cavalry only “squeezed” the Russians beyond Utica by 9 o'clock, but was no longer able to develop the offensive and was bogged down in protracted battles until the end of the battle.

The French launched their main attack on Bagration's flèches, where a fierce battle broke out. Davout's and Ney's infantry corps and Murat's cavalry repeatedly attacked and captured Russian positions, but each time, unable to withstand the bayonet attack, they rolled back. The density of fire was constantly increasing. If the first attack on the flèches was supported by 102 guns, then before the third attack, the Russian positions were already being shelled by 160 guns.

The battles for Bagration's flèches brought together worthy opponents, heroism and self-sacrifice were commonplace for both soldiers and generals. Leading a counterattack, General Mikhail Vorontsov received a bayonet wound and was out of action, General Neverovsky was carried out of the battle shell-shocked. Their divisions perished almost entirely on the flèches. At the head of the counterattacking infantry column, Shevardina's hero General Gorchakov received a serious wound.

The Russian generals were not inferior in valor to their opponents. Marshal Murat attacked the flèches at the head of the cuirassier division and during the fourth attack he almost fell into captivity when he tried to stop the retreating infantry. Marshal Davout broke into the left flèche at the head of the columns of the 5th Infantry Division, but was shell-shocked and knocked off his horse. In the hand-to-hand combat on the flèches, Generals Desse and Compans received serious wounds.

In the fifth attack, the French again captured the flèches, but were knocked out of them by a counterattack. In this battle, shrapnel cut short the life of General Alexander Tuchkov when he led his soldiers in a counterattack with a banner in his hand. The French chief of staff of the 1st Corps, General J. Romef, did not return from the attack. In the second attack, the division of Ch. Morand from the Beauharnais Corps took the Kurgan Heights, defended by the 26th Infantry Division of Major General Ivan Paskevich, and began to consolidate their position there. At this time, the corps of Marshals Davout and Ney, under a powerful artillery barrage, stormed the flèches for the sixth time. This attack was repelled by fire from Russian batteries.

When the flanking shelling of Bagration's positions began from the captured Kurgan Heights, the seventh attack of the flèches followed. The corps of Davout and Ney again went for a frontal assault. Junot's corps tried to bypass the flèches from the right and strike them in the flank. But the infantry corps of General Karl Baggovut, transferred here on the initiative of Barclay de Tolly, stood in the way of the French. Baggovut's fresh regiments, which had previously observed the battle from afar, immediately threw back Junot's corps. General Ermolov, taking the initiative, organized a counterattack on the Kurgan Heights. He personally led the regiments with bayonets, and the heights were liberated. In this battle, the only French general, Charles Bonami, was captured, having fought desperately and received twelve wounds.

The battle had been going on for 6 hours, but the French, despite their enormous efforts and heavy losses, were unable to break the Russian resistance in any key area of the defense. Napoleon had only one chance to win the battle – to strike a powerful blow with all his forces at Bagration's position and break through the Russian defense. At 11:30 am, Napoleon threw 45,000 men, supported by 400 guns, into the eighth attack on the flèches.

The French attack was so powerful that the Russians could not hold out and retreated. Not allowing the French to consolidate their position, Bagration led his troops in a counterattack. At that moment, a cannonball fragment shattered his left leg. The chief of staff of the 2nd Army, General Emmanuel Saint-Priest, was also out of action with a serious wound. The counterattack petered out, and the troops began to roll back to the village of Semenovskaya. Alexei Yermolov, recalling this moment of the battle, wrote in his memoirs: “In an instant, the rumor of his (Bagration’s) death spread, and it was impossible to keep the troops from confusion. Around midday, the 2nd Army was in such a state that some of its units could only be brought into order by firing a shot away.”

The guard regiments sent by Kutuzov from the reserve courageously held back the attacks of the French cavalry, giving the retreating units the opportunity to consolidate their positions on the new line. General Dokhturov, who took command of the left flank of the Russian forces, quickly brought the army, which was in “great confusion,” into order and organized a defense on the new line about a kilometer from the village of Semenovskaya.

Napoleon thought that the battle had reached a turning point: all that remained was to capture the Kurgan Heights, break through the center of the Russian forces, and, having pressed the retreating units to the bank of the Moskva River, complete their rout. He ordered the Young Guard to attack the Kurgan Heights. At that moment, he was informed that the rear of the army was being attacked by the Cossacks. It was Kutuzov, sensing the critical moment of the battle, who sent the cavalry corps of Fyodor Uvarov and the Cossacks of Matvey Platov to bypass the French left flank.

This raid caused confusion in the rear units of the French, forced Napoleon to postpone the attack for two hours and return the Young Guard to the reserve. In order to understand the situation, the French emperor even rode out to the left flank of his army. The Russians gained time to regroup their forces, organize a defensive line on the left flank and strengthen the center.

From a combat point of view, the cavalry raid was of little use. Uvarov's cavalrymen near the village of Bezzubovo were stopped by an infantry regiment that had managed to form a square, and a cavalry brigade. Platov's Cossacks, having crossed the Voina north of the village of Bezzubovo, came to the rear of the French. But instead of striking at the reserve regiments and capturing batteries from the rear, the Cossacks rushed to plunder the French convoy.

Kutuzov clearly expected more from the raid, perhaps hoping to seize the initiative in the battle. It is characteristic that after the battle, of all the generals who participated in it, only Uvarov and Platov were not nominated for awards.

At 2 p.m. Napoleon launched a powerful attack on the center of the Russian positions. More than 300 guns fired at the Kurgan Heights from the front and flanks. Before the attack on the Kurgan Heights, Auguste Caulaincourt told Napoleon: “I will be there this very hour, dead or alive!” He kept his promise, his cuirassiers stormed the heights and almost all of them died there, led by their general. The defenders of the heights fulfilled their military duty to the end. General Pyotr Likhachev, uniting the surviving defenders of the Raevsky battery, led them in a final counterattack. He was seriously wounded in hand-to-hand combat and taken prisoner. Napoleon, amazed by the general's valor, returned his sword to him. But Likhachev refused to accept the weapon from the hands of the enemy.

By 15:00, at the cost of enormous casualties, the French had taken the Kurgan Heights, but were unable to break through the center of the Russian positions. The Russian infantry, having retreated behind the Goretsky Ravine, consolidated their position and did not leave it until the end of the battle. Led by Barclay de Tolly, who personally led the counterattacks, the troops of the 1st Army did not allow the French to develop their emerging success.

The French infantry no longer had the strength to attack, and the battle turned into a furious cavalry skirmish. Between the Kurgan Heights and the village of Semenovskoye was the only relatively flat area where the French could conduct attacks with large cavalry forces. Here, the cavalry corps of Latour-Maubourg and Montbrun repeatedly rolled onto the Russian positions, unable to break through the dense infantry formations and repelled by cavalry counterattacks and artillery.

After 17:00, the advancing impulse of the French cavalry, which had suffered enormous losses, dried up, and the battle began to die down. Only artillery exchanges continued until darkness. At dusk, Napoleon withdrew the cavalry from the captured positions closer to the water, and the infantry remained to spend the night next to the corpses of the dead. Both armies began to put their thinned out units in order and count their losses.

The bloodiest battle ended in a draw. The French were unable to defeat the Russian army, which, although it was driven out of almost all the positions it had occupied at the beginning of the battle, retreated 1-1.5 km, occupied new ones and stood firm in them. “Of all my battles,” Napoleon wrote later, “the most terrible was the one I fought near Moscow. The French proved themselves worthy of victory in it, and the Russians earned the right to be invincible.”

The mass heroism and dedication of the soldiers made the battle extremely fierce and stubborn. This is also evidenced by the small number of trophies. Both sides captured a dozen and a half guns, a thousand prisoners, including one wounded general. But they did not take a single banner, which at all times symbolized the defeat of the enemy.

Human losses, on the contrary, were staggering. The French lost more than 30,000 people (according to some sources, up to 50,000), including 10 killed and 39 wounded generals. The French cavalry suffered especially, with losses reaching 60 percent.

The Russian army lost about 46 thousand people, including 29 generals (6 killed and 23 wounded). An irreparable loss for Russia was the fatal wounding of Bagration, one of the best generals of the Suvorov school, and the death or serious wounding of many military leaders beloved by soldiers.

The consequences of the battle were much more significant than its material results. Leo Tolstoy understood this with amazing depth: “The moral strength of the French attacking army was exhausted. Not the victory that is determined by the pieces of material caught on sticks, called banners, and the space on which the troops stood and stand, but a moral victory, one that convinces the enemy of the moral superiority of his enemy and of his own impotence, was won by the Russians at Borodino.”

The Russian army perceived Borodino as a victory, and the Emperor and Russian society assessed the battle in the same way. Alexander I promoted Kutuzov to General Field Marshal and granted him one hundred thousand rubles. The retreat from Borodino and abandonment of Moscow was viewed by the Russians not as an escape from the pursuing victor, but as a tactical maneuver to continue the fight and finally defeat the enemy. And this maneuver justified itself. The French were unable to advance further than Moscow, and on October 18 their retreat began, which, under the blows of the Russian troops, grew into a mass flight.

V.V. Vereshchagin. Napoleon I on the Borodino Heights

F. A. Roubaud. Guards regiments repel attacks of French cavalry. Fragments of panorama “Battle of Borodino”

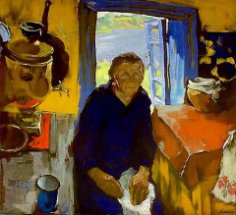

Peter Hess. The Battle of Borodino

F. A. Rubo. Gorki – the command post of the Russian commander-in-chief Mikhail Illarionovich Kutuzov. Fragments of the panorama “The Battle of Borodino”

Illustration to the poem by M.Yu. Lermontov “Borodino”. Chromolithograph by N. Bogatov. 1912.

Refusal of the captured Russian general P.G. Likhachev to accept the sword from Napoleon's hands. Chromolithograph by A. Safonov. Beginning of the 20th century.

F. A. Roubaud. Cavalry battle in the rye. Fragments of the panorama “The Battle of Borodino”

V.V. Vereshchagin. The End of the Battle of Borodino