Advisors from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) will meet this week to discuss several scheduled childhood vaccines. (Photo: Andrew Harnick via Getty Images)

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC) influential vaccine advisory committee, which was reconstituted by Health and Human Services (HHS) Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr., will meet Thursday and Friday (September 18 and 19) to discuss changes to the childhood vaccination schedule.

Experts say these changes could make American children less healthy.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) meeting, which begins Thursday, will focus on the hepatitis B vaccine, as well as the MMRV vaccine—a variant of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine that also protects against chickenpox. Currently, the first dose of the hepatitis B vaccine is recommended at birth, and the first dose of the MMRV vaccine is recommended at 12–15 months of age.

You may like

-

COVID-19 vaccines for children are in limbo due to conflicting federal recommendations.

-

We're debunking (many) false claims made by RFK Jr. about COVID vaccines.

-

Robert Kennedy Jr. wants to reform the country's “vaccine court.” Here's what's stopping him.

The discussions initiated by ACIP are raising alarm among outside experts, who argue that there is no new evidence to suggest these recommendations are problematic and that the current schedule is well-studied and highly effective in preventing these dangerous infections.

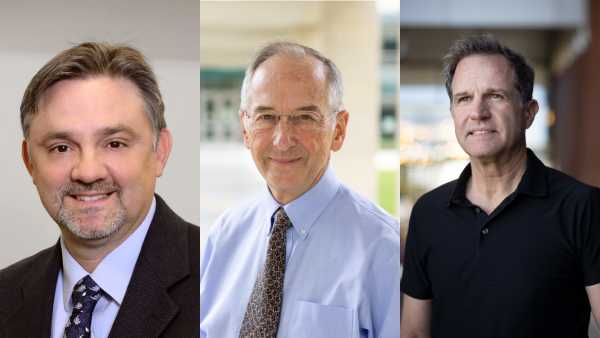

“It's a resounding success,” said Dr. William Schaffner, professor of preventive medicine at Vanderbilt University School of Medicine, regarding the recommendation to vaccinate all children against hepatitis B at birth. Schaffner was a member of ACIP in the 1980s and served as its representative to various organizations from 1986 to 2024. “If we change this, we'll start seeing cases again,” he said.

Protection against hepatitis B in infants

Kennedy is the founder of Children's Health Defense, a nonprofit known for its campaign against childhood vaccines. He stepped down as the group's chairman before taking a position at the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. In June, he fired 17 current ACIP members and replaced them with new members, some of whom gained notoriety for promoting unproven COVID-19 treatments and criticizing universal vaccination.

The two routine childhood vaccines the committee will vote on this week are not new. The MMR vaccine was first licensed in 1971, and the MMRV vaccine, which adds protection against chickenpox to the same vaccine, was approved in 2005. The hepatitis B vaccine has been recommended for newborns for over 30 years, since 1991.

Vaccination immediately after birth protects infants from contracting the virus from their mother during childbirth. This is because the virus is spread through bodily fluids, including blood, saliva, menstrual fluid, vaginal secretions, and semen, and can be transmitted to the baby through the birth canal.

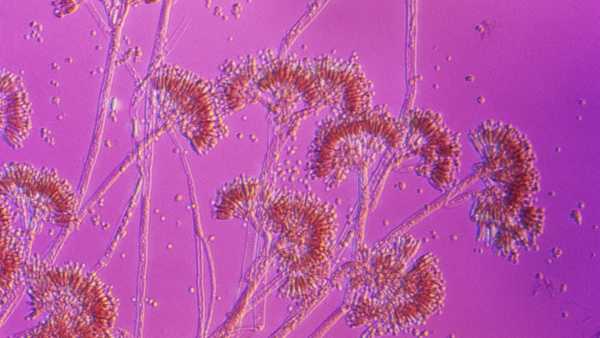

Hepatitis B is a viral infection that can become chronic, especially in people infected in infancy. It can easily go undetected, leading to liver damage and an increased risk of liver cancer. Once chronic, the infection becomes persistent, requiring antiviral medications and vaccinations, and can lead to the need for a liver transplant. Mothers are screened for the infection, but sometimes its presence goes undetected, putting infants at risk, Higgins said.

On Tuesday (September 16), former CDC officials told KFF Health News that the ACIP will likely recommend delaying vaccinations until age 4.

You may like

-

COVID-19 vaccines for children are in limbo due to conflicting federal recommendations.

-

We're debunking (many) false claims made by RFK Jr. about COVID vaccines.

-

Robert Kennedy Jr. wants to reform the country's “vaccine court.” Here's what's stopping him.

“Tomorrow you'll hear the argument that we can identify mothers who test positive, vaccinate their children as early as possible, and wait until the rest of us are a little older before vaccinating them,” Schaffner said. “We tried that. It didn't work.”

“Those children who fall into the cracks,” he said, “are now at risk of infection and subsequent liver damage, cancer and death.”

Anti-vaccination advocates argue that vaccinating newborns is unnecessary because hepatitis B is often spread to adults through intravenous drug use or sexual intercourse. However, according to Higgins, before the introduction of newborn vaccination, approximately 18,000 cases of hepatitis B were reported annually in the United States in children under 10 years of age. In approximately half of these cases, the source of infection was unknown. Children can become infected with the virus even through contact with a small amount of blood, such as from a scraped knee, a shared toothbrush touching bloody gums, or a bite from a child at daycare.

By comparison, in 1990, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were three new cases of hepatitis B per 100,000 children and adolescents in the United States. By 2002, that rate had dropped to 0.3 per 100,000. Today, it is less than 0.1 per 100,000.

The benefits continue into adulthood: because the vaccine provides long-lasting protection, hepatitis B incidence among people aged 30 to 39 years (first vaccinated in infancy) declined sharply after 2015.

“There are virtually no negative consequences from this,” Dr. Michelle Barron, senior medical director of infection prevention and control at the UCHealth hospital system in Colorado, told Live Science. “The vaccines are safe.”

MMRV vaccine

According to the current vaccination schedule, children receive the first dose of the MMRV or MMR vaccine along with the chickenpox vaccine between the ages of 12 and 15 months. The second dose is administered between the ages of 4 and 6 years and typically provides lifelong immunity.

For three years after the introduction of the MMRV vaccine, researchers noted an increased risk of febrile seizures, or seizures caused by fever, in children who received the MMRV vaccine compared to the MMR and varicella vaccines alone. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the risk of seizures from MMRV is twice that from MMR in children aged 1 to 2 years, corresponding to one additional febrile seizure for every 2,300 to 2,600 doses of MMRV administered in this age group.

“We—and by 'we,' I mean pediatricians, vaccination experts, and ACIP—were rightfully concerned about this, and there was an incredibly thoughtful discussion about how to change the recommendations,” said Dr. David Higgins, associate professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. The committee decided that it's preferable for children under 4 to receive the measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella vaccines separately.

However, because the risk of febrile seizures associated with the vaccine is small, the committee left the option open for parents who would like to give their children one less needle to choose the MMRV vaccine after reviewing its risks and benefits.

Vaccinating newborns in the United States against hepatitis B has significantly reduced the number of cases of the disease nationwide.

Overall, 2% to 5% of children under 5 years of age occasionally experience seizures in response to fever (caused by infection or vaccination), and about a third of children who have had one febrile seizure will have more. Although children with a history of febrile seizures have a slightly higher risk of developing epilepsy later in life, in almost all cases, febrile seizures are harmless and resolve with age.

Higgins told Live Science that if ACIP restricts patients' ability to receive the MMRV vaccine, clinics using the vaccine would likely face supply issues.

Both MMRV and MMR vaccines prevent measles, which can cause fatal pneumonia, brain swelling, loss of immune memory, and sometimes a progressive and fatal neurological disease called subacute sclerosing panencephalitis (SSPE). They also prevent mumps, a viral infection that can lead to deafness and male infertility, and rubella, a viral infection that causes fever and rash and can lead to heart and brain abnormalities in the fetus in pregnant women.

The chickenpox vaccine not only prevents the painful, itchy viral infection, but also reduces the risk of children developing shingles—a blistering rash caused by the same virus that causes chickenpox, but which reactivates in the nervous system long after the initial infection has cleared.

Creating contradictions

A 2017 statement from the American Academy of Pediatrics summarized the hepatitis B vaccine safety data from the Vaccine Safety Datalink, a large-scale vaccine safety monitoring project initiated in 1990. According to the data, “there is no evidence of a causal association between hepatitis B vaccination and neonatal sepsis or death, rheumatoid arthritis, Bell’s palsy, autoimmune thyroid disease, hemolytic anemia of childhood, anaphylaxis, optic neuritis, Guillain-Barré syndrome, sudden sensorineural hearing loss, or other chronic diseases.”

There are no signs of new data emerging that would change this conclusion. However, according to Barron, raising this issue at the ACIP meeting will likely increase general hesitancy toward vaccination.

“This is all just noise designed to sow skepticism and anxiety around vaccines in general,” Barron said. “This multifaceted attack on vaccines that have been around for 30 to 40 years and have been used safely and effectively all that time, without new research, without new data—I truly believe it's just another tactic to scare people.”

The meeting could also serve as an opportunity to spread concerns about the timing of the childhood vaccination schedule in general—a frequent target of anti-vaccination campaigns. While activists claim the schedule's safety hasn't been studied, this is untrue.

“At every stage, a study is conducted to determine whether a new vaccine added to the schedule will cause significant side effects,” Schaffner said. “This is before recommendations are made.”

After a new vaccine is added to the vaccination schedule, numerous safety reporting systems exist to track any adverse events not identified in trials, such as the one that revealed an increased risk of febrile seizures in young children with MMRV vaccination. These systems allow for long-term studies to identify serious population impacts over time, Higgins said. And “we found no significant association.”

The American Health Insurance Partnership (AHIP), an industry group for private insurers, announced in a statement on September 16 that insurers will continue to cover vaccines recommended as of September 1, 2025, until at least the end of 2026. However, half of children in the United States receive vaccines through the federal Vaccines for Children program, and ACIP recommendations directly determine which vaccines are included in that program.

RELATED STORIES

A prominent medical journal has rejected the Russian Foundation for Critical Care's (RFK) call to retract the vaccine study.

Thimerosal poses no health risks and is rarely used. So why are anti-vaxxers so obsessed with it?

Are you protected from measles? Do you need a booster shot? Everything you need to know about immunity.

The program primarily targets uninsured and underinsured children; children who are enrolled in or eligible for Medicaid; and American Indian or Alaska Native children who are eligible for assistance under the Indian Health Care Improvement Act.

“While I'm pleased to see insurance companies saying, 'We think vaccines are important and we'll cover them,'” Higgins said, “I'm really concerned about the fate of the half of children in the U.S. who receive vaccines through the Vaccines for Children program.”

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and does not contain medical advice.

Stephanie Pappas, Social Link Navigator, Live Science Contributor

Stephanie Pappas is a freelance writer for Live Science, covering a wide range of topics, from geological sciences and archaeology to the human brain and behavior. Previously a senior writer for Live Science, she now works as a freelance writer in Denver, Colorado, and regularly contributes to Scientific American and The Monitor, the monthly magazine of the American Psychological Association. Stephanie earned a bachelor's degree in psychology from the University of South Carolina and a graduate certificate in science communication from the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Read more

COVID-19 vaccines for children are in limbo due to conflicting federal recommendations.

We're debunking (many) false claims made by RFK Jr. about COVID vaccines.

Robert Kennedy Jr. wants to reform the country's “vaccine court.” Here's what's stopping him.

'These decisions were completely reckless': Cutting funding for mRNA vaccines will make America more vulnerable to pandemics.

Vaccines show promise in the fight against dementia

Experts warn that the RFK's proposal to allow bird flu to spread through poultry could lead to a pandemic.

Latest news on medicine and drugs

An innovative drug for the treatment of cystic fibrosis, which extends life by decades, has earned its developers an “American Nobel Prize” of $250,000.

A study has found that just one dose of LSD can relieve anxiety for months.

RFK Jr. wants to reform the country's “vaccine court.” Here's what's stopping him.

We're debunking (many) false claims made by RFK Jr. about COVID vaccines.

Does cannabis increase the risk of cancer?

You may not be allergic to penicillin. Here's how to find out.

Latest news

Robert Kennedy's hand-picked advisers will be arriving to discuss the childhood vaccination schedule. Here's what you need to know.

'It's impossible to put the genie back in the bottle': Readers believe it's too late to stop the development of artificial intelligence

The oldest known dinosaur with a domed head has been discovered protruding from a rock in Mongolia's Gobi Desert.

A 'rare' ancestor reveals how giant flightless birds reached distant lands.

'The Sun is slowly waking up': NASA warns that extreme space weather could become even more extreme in the coming decades

Scientists have invented a new sunscreen made from pollen.

LATEST ARTICLES

1What are “magic numbers” in nuclear physics and why are they so powerful?

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-explainer,van-disable-comments,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com