A Burmese python was forced to vomit a white-tailed deer when temperatures in Florida dropped to 50 degrees Fahrenheit. (Photo: Travis Mangione, U.S. National Park Service)

A Burmese python in Florida's Big Cypress National Wildlife Refuge regurgitated an entire white-tailed deer after temperatures in South Florida dropped below 50 degrees Fahrenheit (10 degrees Celsius) late last year, well below the cold-blooded creature's comfortable range.

Although pythons are known to regurgitate their prey in cold laboratory conditions, scientists have never caught these elusive snakes doing so in the wild—until now. The unusual observation, made in late November 2024, is described in a study published in July in the journal Ecology and Evolution.

You may like

-

A tourist picked up a venomous snake and died after the bite triggered a rare allergic reaction, authorities say.

-

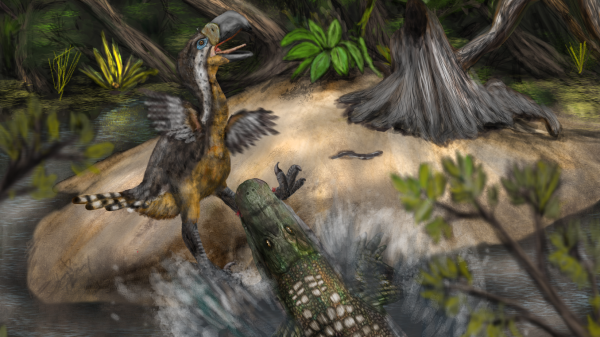

Bite marks suggest that the giant terror birds may have been potential prey for another predator – the enormous caiman.

-

New viruses discovered in bats in China

Burmese pythons (Python bivittatus) have been an invasive species in Florida since the late 1970s. Despite their long-standing presence, they are poorly studied, and gaps exist in our knowledge of the snakes' biology and their interactions with native species, such as deer.

Deer numbers in the preserve are declining, which is concerning because they form an important part of the diet of local predators such as Florida cougars (Puma concolor coryi). To learn more about how often snakes eat deer and how quickly they digest them, preserve scientists spent a year monitoring the digestion of several large female pythons—those considered most likely to consume deer.

One of the observed snakes had a large lump in its stomach, indicating it had eaten something the size of a deer. However, over the next few days, the lump did not seem to shrink.

A week after first being observed eating a large food pellet, the Burmese python is resting in the water while continuing to digest its food.

After a cold night, when the temperature in the reserve dropped to 9.4°C, scientists examined the snake again. They found it, unclumped, floating in the shallows of a willow swamp next to a nearly undigested white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) it had regurgitated.

“They found it completely empty, but they were able to smell a deer nearby and put two and two together,” Sandfoss said.

The 2.5-year-old, 61-pound (28-kilogram) white-tailed deer was minimally digested, even after spending about 10 days inside the snake.

Because snakes are cold-blooded, or poikilothermic, they struggle to function in cold conditions. Their biological processes, including digestion, slow down until the temperature rises.

You may like

-

A tourist picked up a venomous snake and died after the bite triggered a rare allergic reaction, authorities say.

-

Bite marks suggest that the giant terror birds may have been potential prey for another predator – the enormous caiman.

-

New viruses discovered in bats in China

If the outside temperature drops too low, a snake's food can begin to decompose in its stomach faster than it can digest it, leading to a buildup of bacteria. In response, the snake vomits to rid itself of the bacteria. This can be an energy-consuming activity for an already hungry snake, but the snake in the study survived.

According to Sandfoss, since the Burmese python is an invasive species in Florida, the snake's survival has complex consequences. It missed one of its largest meals, which it only eats a few times a year, so it may lack the energy to reproduce, which could help control the python population. Alternatively, the snake may kill another deer to replenish its lost energy, further threatening the deer population that local predators rely on.

“Deer populations in Big Cypress have been declining for several years, and we believe pythons are playing a significant role,” lead study author Travis Mangione, a biologist with the National Park Service (NPS), told Live Science. “Because this python survived the vomiting, it will continue to feed on local wildlife.”

RELATED STORIES

— A 200-pound “monster” Burmese python has finally been captured in Florida after five men boarded it.

— A Burmese python ate an even larger reticulated python alive in a first-of-its-kind encounter.

— “Truly primal”: Watch a Burmese python swallow a deer whole in the Florida Everglades by stretching its jaws to the limit.

While scientists study how Burmese python vomiting affects local ecosystems, observations of them in the wild provide valuable information about how far this invasive species may spread within the United States. Temperature is a key factor limiting the snakes' range, and the lowest temperature they can survive may be the lowest they can digest, Sandfoss said.

The new study is part of a larger, as-yet-unpublished project analyzing python diet data for an entire year. Scientists working on the project hope it will shed light on the basic biological process of digestion in Burmese pythons, which remains poorly understood.

“Pythons have complex biology, and we've never encountered an animal of this scale—an animal this large, aggressive, terrestrial, poikilothermic,” Sandfoss said. “We're trying to figure all these questions out.”

Snake Quiz: What Do You Know About Slithering Reptiles?

KR Callaway, Live Science researcher

K.R. Callaway is a freelance journalist specializing in science, health, history, and politics. She holds a bachelor's degree in classics from the University of Virginia and is currently pursuing a master's degree in science, health, and environmental reporting at New York University.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

A tourist picked up a venomous snake and died after the bite triggered a rare allergic reaction, authorities say.

Bite marks suggest that the giant terror birds may have been potential prey for another predator – the enormous caiman.

New viruses discovered in bats in China

A scientist's cat has once again helped discover a rare virus.

Texas cougar genes are saving Florida cougars from extinction—for now.

Night lizards survived an asteroid collision that could have wiped out the dinosaurs, despite living right next to the impact site.

Latest news about snakes

Scientists have discovered that Burmese pythons have previously unseen cells that help them digest entire skeletons.

A Florida lynx bit the head off a 13-foot Burmese python in the Everglades.

'A Speeded-Up Version of Darwin's Evolution': How a Cold Snap in Florida Could Have Caused Burmese Pythons to Evolve at Incredibly Fast Speeds

Snake Quiz: Let's test what you know about these crawling reptiles.

Why do snakes shed their skin?

A venomous snake with three fangs may be the 'world's most dangerous deadly viper'.

Latest news

Who's Eligible for the COVID Vaccine This Year? Everything You Need to Know

If tiny lab-grown “brains” became conscious, could they be experimented on?

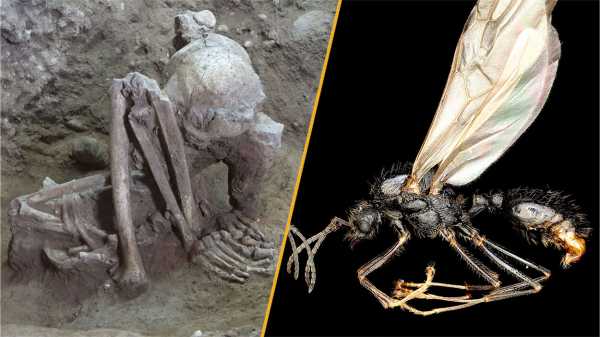

This week's science news: The world's oldest mummy and an ant mating with clones of a distant species

A huge source of the rare earth metal niobium was brought to the surface when the supercontinent broke apart.

A cold snap in Florida caused a Burmese python to vomit up an entire deer.

Watch the sky! This October, you'll be able to see two bright comets on the same night during a meteor shower.

LATEST ARTICLES

1Why does Pluto have such a strange orbit?

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com