Cologne has long been a part of our lives, and it's no wonder it's considered one of the best gifts for men. But by historical standards, cologne is relatively new, only 300 years old.

The world of fragrances has always surrounded people, so naturally, humans also wanted to impart a pleasant scent to their bodies. For a long time, aromatic oils, resins, and powders were used for this purpose. When the Arabs invented the distiller, the first attempts were made to create the prototypes of cologne as we know it—solutions of essential oils and aromatic resins in grape alcohol. However, these were not widely used. More often, tinctures were made with alcohol for medicinal rather than cosmetic purposes.

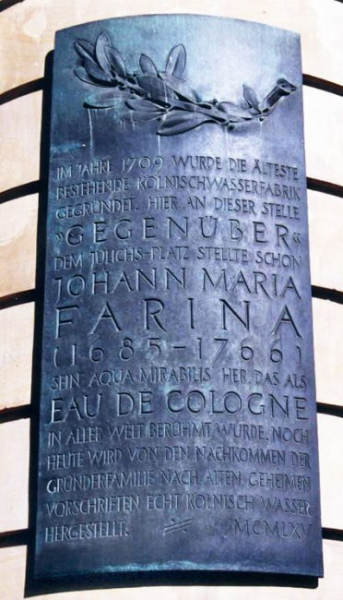

It is believed that the commercial production of aromatic oil solutions in grape alcohol began with Florentine perfumers in the early 17th century. The birth of the famous cologne is considered to be 1709. It originated in Cologne, where Italian-born Giovanni Maria Farina ran a perfume shop. Giovanni received a recipe from his uncle, Paolo Feminis, for an aromatic water consisting of an alcohol solution with rosemary, lavender, and bergamot, which he decided to perfect.

Giovanni based his new composition on citrus oils (lemon, orange, mandarin, and grapefruit), adding cedarwood, bergamot, and several herbs. While developing the recipe, he described it in a letter to his brother: “My scent is reminiscent of a spring morning in Italy after rain: oranges, lemons, grapefruit, bergamot, citron, the flowers and herbs of my homeland.” The author named the aromatic solution he had invented in honor of the city where it was invented— Eau de Cologne (Cologne Water).

It's hard to say that cologne immediately began its triumphant march across the globe. There was demand for this new perfume, and production increased, but it didn't spread beyond Cologne, although travelers and merchants gradually began to distribute it throughout Europe. Oddly enough, the war actually helped facilitate its spread.

During the Seven Years' War (1756–1763), which involved many European countries, Cologne was captured by French troops under the command of the Count of Clermont. The brave French soldiers took a liking to cologne, which had a pleasant aroma, effectively disinfected the skin, and helped conceal the odor of sweat. Thanks to the military, the cologne soon made its way to Paris, where it quickly gained widespread popularity. It was then that its rapid spread across Europe began.

The French nobility, despite their refined manners and opulent attire, didn't bother with hygiene. Historically, this was the case: even the Russian princess Anna, who became Queen of France, complained to her father in Kyiv that people in Paris didn't wash and the stench was terrible. Therefore, cologne, which helped mask the odor of sweaty and unwashed bodies, proved to be a welcome addition. It began to be purchased in enormous quantities, and the company founded by Giovanni Farina experienced a period of prosperity.

Back then, cologne wasn't yet a male prerogative. Women literally doused themselves with it, too. At the French court, Madame du Barry, Louis XV's mistress, became a particular fan of this fragrant newcomer.

Around the same time, “Cologne Water” arrived in Russia, gifted to Catherine II by her former enemy in the Seven Years' War, King Frederick II of Prussia. The empress was delighted with the new product. Naturally, the cologne immediately became extremely popular among the court, and then among the nobility. Paul I moderated the nobility's ardor for cologne consumption somewhat, but his reign was short-lived. The new emperor, Alexander I, began to receive cologne from Cologne again.

Incidentally, Alexander's chief military adversary, Napoleon Bonaparte, was also extremely fond of cologne, which he believed helped clear the mind. The French emperor didn't limit himself to using cologne for its intended purpose. He gargled with it, added a drop of it to the sugar he drank with his tea (apparently, he was significantly ahead of our boozers in consuming cologne internally), and added it to his bath water. According to contemporaries, Napoleon required up to 12 bottles of cologne daily.

By the end of the 19th century, many different perfumes based on alcohol solutions were already being produced around the world, but the famous “Eau de Cologne” continued to hold the lead, and the company created by Giovanni Farina supplied it to many royal courts of Europe.

Russia also developed its own colognes. Specifically, their production was carried out by the Moscow branch of the company of the famous perfumer François Coty. It was he who invented the Chypre cologne, so beloved by men in the Soviet Union.

Today, cologne remains highly popular, although it has been somewhat undermined by various eau de toilettes, deodorants, lotions, and aftershave balms. We, however, have our own unique characteristics, firmly entrenched in jokes. There's even a popular belief that “Triple” cologne is intended for internal rather than external use. Apparently, Napoleon's example proved contagious.

In the birthplace of “Cologne Water,” the memory of the famous “Eau de Cologne” and its creator, who made their city famous, is sacredly preserved. A large museum has been established there, where you can trace the entire history of “Cologne Water,” see the authentic utensils and accessories used by Giovanni Farina, and “taste” the fragrances. Even the unique bottles in which the famous “Eau de Cologne” was delivered to European monarchs have been preserved.

The museum is a popular destination for tourists, many of whom, after learning about the history of the famous “Cologne water,” buy an elegant bottle of genuine “Eau de Cologne” as a souvenir. The souvenir isn't cheap, but the amazing 300-year-old fragrance is worth it.

Giovanni Maria Farina

An exhibition at the Cologne Water Museum

An exhibition at the Cologne Water Museum

An exhibition at the Cologne Water Museum

A memorial plaque to the creator of the famous “Cologne Water”