Unfortunately for demographers, fertility rates are difficult to predict long-term. (Image credit: gremlin via Getty Images)

Pronatalism—the belief that low birth rates are a problem that needs to be solved—is experiencing a new wave of popularity in the United States.

With the birth rate declining in the US and around the world, concerns are being raised from Silicon Valley to the White House about the potential catastrophic economic impact of a sharp population decline. The Trump administration has stated that it is seeking ideas to encourage Americans to have more children, as the US is experiencing its lowest overall fertility rate on record, having fallen by approximately 25% since 2007.

You may like

-

“We know what to do; we just need to implement it.” Pregnancy in the US is more dangerous than in other rich countries. But we can fix it.

-

A $14,000 pregnancy robot from China doesn't exist. But is such technology even possible?

-

“I Would Never Let a Robot Carry My Baby”: A Poll on “Pregnancy Robots” Divides Live Science Readers

The demographic collapse theory is based on three key fallacies. First, it distorts fertility information obtained through standard fertility rates and makes unrealistic assumptions that fertility rates will follow predictable patterns into the distant future. Second, it exaggerates the impact of low fertility on future population growth and size. Third, it ignores the role of economic policy and labor market changes in assessing the impact of low fertility.

Fertility fluctuations

Demographers typically estimate the birth rate in a population using a metric called the total fertility rate. The total fertility rate for a given year is an estimate of the average number of children women would have in their lifetime if they maintained their current fertility rate throughout their childbearing years.

Fertility rates aren't static—in fact, they've changed significantly over the past century. In the US, the total fertility rate rose from approximately 2 births per woman in the 1930s to a peak of 3.7 births per woman around 1960. It then fell below 2 births per woman in the late 1970s and 1980s, before returning to 2 births per woman in the 1990s and early 2000s.

Since the Great Recession, which lasted from late 2007 to mid-2009, the total fertility rate in the United States has declined almost every year, with the exception of a very small increase following the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021 and 2022. In 2024, it reached a record low, falling to 1.6. This decline is primarily due to a decline in births among teenagers and people in their early 20s, often unintended.

But while the total fertility rate provides a snapshot of the fertility situation, it is not a perfect indicator of how many children a woman will ultimately have if fertility patterns change, for example if people delay having children.

Imagine a 20-year-old woman today, in 2025. The total fertility rate suggests that when she turns 40, she will have the same fertility rate as today's 40-year-olds. This is unlikely to happen, because in 20 years, the fertility rate among 40-year-olds will almost certainly be higher than today, as more children are being born at older ages and more people can overcome infertility with assisted reproductive technology.

A more detailed picture of childbirth

Because of these problems with the total fertility rate, demographers also measure the total number of births women have by the end of their reproductive years. Unlike the total fertility rate, the average number of children born to women aged 40 to 44 remains fairly stable over time, fluctuating around two.

You may like

-

“We know what to do; we just need to implement it.” Pregnancy in the US is more dangerous than in other rich countries. But we can fix it.

-

A $14,000 pregnancy robot from China doesn't exist. But is such technology even possible?

-

“I Would Never Let a Robot Carry My Baby”: A Poll on “Pregnancy Robots” Divides Live Science Readers

Americans remain positive about having children. The ideal family size remains two or more children, and nine out of 10 adults already have children or would like to. However, many Americans are failing to achieve their childbearing goals. This is likely due to the high cost of raising children and growing uncertainty about the future.

In other words, it appears that low fertility rates are not due to people not being interested in having children. Rather, they are experiencing a lack of opportunity to become parents or have as many children as they would like.

The problem of forecasting future population size

Standard population projections do not support the idea that the population will decline sharply.

250 years ago, there were one billion people on Earth. Today, there are more than 8 billion, and by 2100, according to UN projections, there will be more than 10 billion. This means that in the foreseeable future, the population will increase by 2 billion, not decrease. Of course, this forecast is plus or minus 4 billion. But this range highlights another important point: the further into the future population projections are projected, the more uncertain they become.

Predicting population size in five years is much more reliable than in 50 years, and forget about it altogether in 100 years. Most population scientists avoid making such long-term forecasts for the simple reason that they are usually wrong. This is because fertility and mortality rates change unpredictably over time.

The US population is also not declining. Currently, despite the fertility rate being below the replacement level of 2.1 children per woman, births still exceed deaths. The US population is expected to grow by 22.6 million by 2050 and by 27.5 million by 2100, with immigration playing a significant role.

Will low birth rates lead to an economic crisis?

A common justification for concerns about low birth rates is that they lead to a host of economic and labor market problems. Specifically, pro-natalists argue that there won't be enough labor to support the economy, and there will be too many elderly people for these workers to support. However, this isn't necessarily true, and even if it were, raising the birth rate wouldn't solve the problem.

As the birth rate declines, the age structure of the population changes. However, a higher proportion of older people does not necessarily mean a lower ratio of employed to unemployed.

First, the share of children under 18 in the total population is also declining, so the working-age population (usually defined as those aged 18 to 64) often changes relatively little. As older adults remain healthier and more active, more of them contribute to the economy. The labor force participation rate among Americans aged 65 to 74 increased from 21.4% in 2003 to 26.9% in 2023 and is expected to increase to 30.4% by 2033. Minor changes in the average retirement age or how Social Security is funded would further reduce the burden on programs supporting the elderly.

Moreover, the pronatalist argument that higher fertility will increase the labor force overlooks some short-term consequences. More children mean more dependents, at least until those children reach the age required to enter the labor market. Not only do children require expensive services like education, but they also reduce labor force participation, particularly for women. With declining fertility, female labor force participation has risen sharply—from 34% in 1950 to 58% in 2024. Pronatalist policies that discourage women from participating in labor contradict concerns about declining labor force participation.

RELATED STORIES

—In which month are the most children born?

Scientists have discovered a surprising factor that can prolong pregnancy.

—The world's first child conceived using remotely controlled “automated IVF” has been born.

Research shows that economic policy and labor market conditions, not the age structure of the population, play a crucial role in determining economic growth in developed countries. Furthermore, with the rapid advancement of technologies such as automation and artificial intelligence, the future demand for labor remains unclear. Moreover, immigration is a powerful and effective tool for addressing labor market challenges and labor force participation.

Overall, there is no evidence to support Elon Musk's claim that “humanity is dying out.” While changes in population structure accompanying low fertility are real, we believe their impact has been greatly exaggerated. Significant investments in education and sound economic policies can help countries successfully adapt to the new demographic reality.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

TOPICS Elon Musk

Leslie Root, assistant professor of research at the Behavioral Sciences Institute at the University of Colorado Boulder

Leslie Root is a demographer and associate professor at the Institute of Behavioral Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, where she also serves as the deputy director of the CU Population Center. Her research focuses on fertility and sexual and reproductive health, with projects examining the impact of social factors such as access to contraception, the COVID-19 pandemic, and pronatalist policies on fertility across the lifespan. She holds a PhD in demography from the University of California, Berkeley, and a master's degree in Eurasian, Russian, and East European studies from Georgetown University.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

“We know what to do; we just need to implement it.” Pregnancy in the US is more dangerous than in other rich countries. But we can fix it.

A $14,000 pregnancy robot from China doesn't exist. But is such technology even possible?

“I Would Never Let a Robot Carry My Baby”: A Poll on “Pregnancy Robots” Divides Live Science Readers

An FDA panel has questioned the safety of antidepressants during pregnancy. Here's what the science really says.

Sperm selection is “entirely dependent on the egg” – so why does the “sperm race” myth persist?

If “pregnancy robots” were a reality, would you use them?

Latest news on fertility, pregnancy, and childbirth

A laboratory study shows that even short-term exposure to air pollution can cause inflammation of the placenta.

Acne drug Accutane may restore sperm production in infertile men, first study suggests.

Scientists have invented “spermbots” that they pilot through an artificial cervix and uterus.

“I Would Never Let a Robot Carry My Baby”: A Poll on “Pregnancy Robots” Divides Live Science Readers

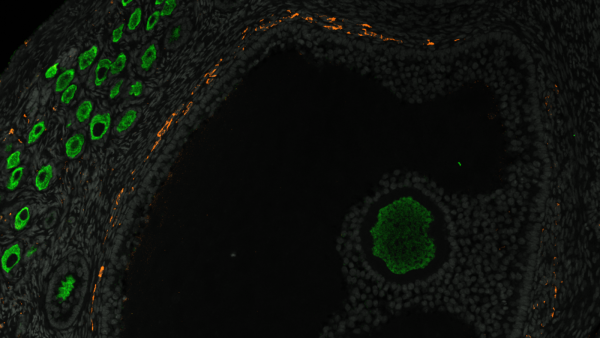

We finally have an understanding of how the egg supply is built up throughout life in primates.

If “pregnancy robots” were a reality, would you use them?

Latest opinions

We are only just beginning to learn what the Earth's inner core is really made of.

Experts say the danger of declining birth rates in the US is “greatly exaggerated.”

“When people gather in groups, strange behavior often emerges”: How the rise of social media has led to the emergence of dysfunctional thinking

'Your concerns are well-founded': How human activity has increased the risk of tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease

How the surface you exercise on can increase your risk of cramping

'Serious negative and unintended consequences': Polar geoengineering is not the answer to climate change

LATEST ARTICLES

1Research claims that eliminating daylight saving time could prevent more than 300,000 strokes per year in the United States.

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-crosspost,type_opinion,exclude-from-syndication,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com