“`html

Researchers have employed an innovative technique to cultivate human eggs within a laboratory setting, enabling them to subsequently undergo fertilization with another individual’s genetic material.(Image credit: Natalia Lebedinskaia via Getty Images)

Scientists have engineered human eggs inside a lab utilizing a method akin to the one employed to replicate the renowned Dolly the sheep, and then used in vitro fertilization (IVF) to transform them into embryos.

Even though this procedure is currently far from practical application, the anticipation is that it might eventually clear the path for novel treatments for infertility.

You may like

-

Scientists grow mini amniotic sacs in the lab using stem cells

-

Incredible, first-of-its-kind video shows human embryo implanting in real time

-

8 babies spared from potentially deadly inherited diseases through new IVF ‘mitochondrial donation’ trial

The initial validation trial was documented on Tuesday (September 30) within the journal Nature Communications.

The egg-creation process entailed extracting the nucleus from a pre-existing human egg cell and substituting it with a nucleus taken from a human skin cell. This preliminary action, termed somatic cell nuclear transfer, has seen utilization in replicating a range of animals, notably Dolly.

Nonetheless, the OHSU researchers intended to produce a viable egg, rather than a clone; eggs possess half the count of chromosomes when contrasted with nonreproductive cells present in the body. During fertilization, the egg’s complement of 23 chromosomes merges with the 23 chromosomes derived from a sperm cell, culminating in a total of 46. In order to encourage their artificially created eggs to relinquish half of their chromosomes, the scientists administered an electric surge in conjunction with a medication referred to as roscovitine, which interferes with enzymes overseeing the cell cycle, which is the mechanism governing cellular division.

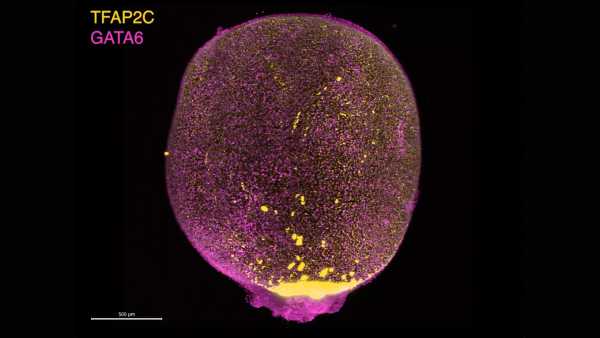

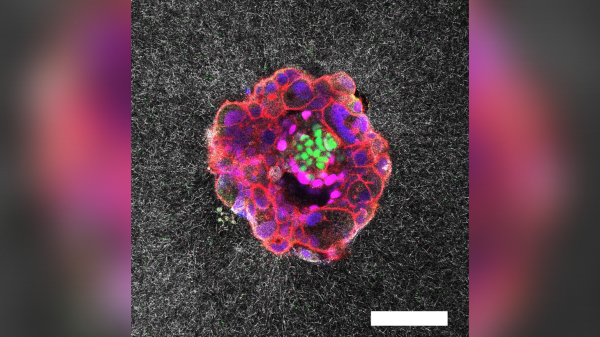

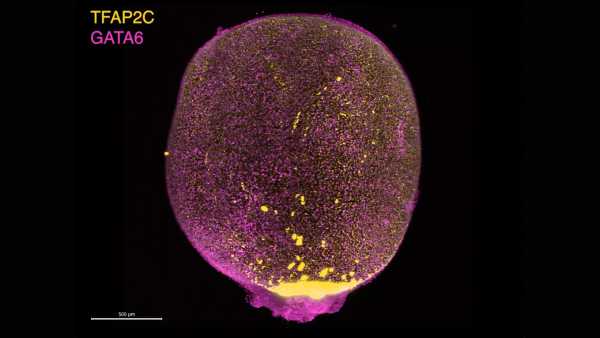

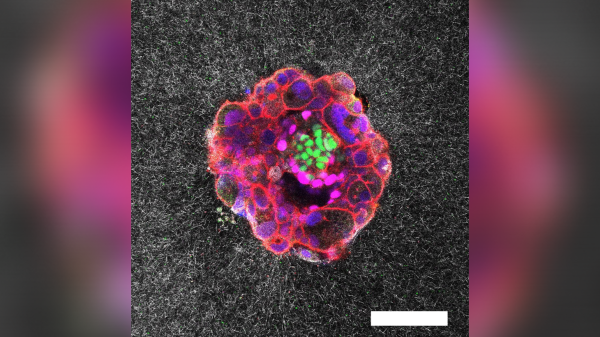

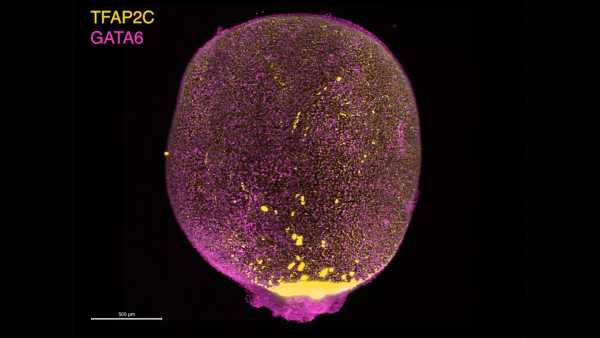

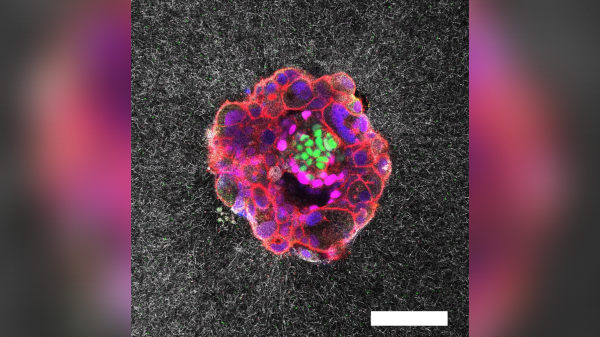

This experiment ultimately yielded 82 egg cells, which were subsequently fertilized with sperm via in vitro fertilization (IVF), as mentioned in the report. However, the fertilization phase is not yet flawless — only about 9% progressed to the “blastocyst” phase. At that juncture, the egg has divided, resulting in a hollow cluster of cells poised for introduction into the womb by means of IVF.

The majority of eggs fertilized in the trial failed to achieve the blastocyst phase; in fact, they merely partitioned enough to generate a total of four to eight cells.

The “modest” blastocyst development pace most likely emanates from a duo of contributing elements, the study’s authors stated within their manuscript. To begin with, chromosomal irregularities likely obstructed the fertilized eggs from undergoing additional division. In addition, the genes incorporated from skin cells were most likely not effectively reprogrammed to perpetuate embryonic growth. Put simply, the genes continued to behave, in particular ways, as though they were situated in skin cells, rather than the cells that take shape in the early stages of development.

The specific problem that posed the greater issue throughout the research remains ambiguous, although it’s plausible that both elements played a role, according to the authors.

You may like

-

Scientists grow mini amniotic sacs in the lab using stem cells

-

Incredible, first-of-its-kind video shows human embryo implanting in real time

-

8 babies spared from potentially deadly inherited diseases through new IVF ‘mitochondrial donation’ trial

The researchers pointed out that none of the eggs achieving the blastocyst stage were nurtured beyond that point, and because they also displayed chromosomal defects, they were unlikely to be adequate for application in IVF. These flaws included an excess or deficiency of chromosomes, even though they generally totaled 46. A few eggs additionally manifested multiple replicates of an identical chromosome, or completely lacked certain chromosomes.

So, for now, the procedure “is excessively unproductive and carries too great a risk for prompt employment in clinical practice,” as stated by Katsuhiko Hayashi from the University of Osaka, a stem cell researcher who was not involved in the study, to Science News.

Furthermore, the study’s authors highlighted that “at the present juncture, it persists as a mere validation of principle, and more investigation is needed to guarantee effectiveness and safety ahead of potential clinical implementations.”

Looking ahead, the team has designs on examining more effective means of coordinating the halving, and consequent doubling, of chromosomes within the egg. The intent is to more precisely capture the processes inherent in a typical human pregnancy, so that the suitable chromosomes are shed during the initial division and then adequately consolidated with novel chromosomes in the course of fertilization.

RELATED STORIES

—Human eggs have special protection against certain types of aging, study hints

—The choice of sperm is ‘entirely up to the egg’ — so why does the myth of ‘racing sperm’ persist?

—We finally have an idea of how the lifetime supply of eggs develops in primates

If this technique can at some point be improved for utility in fertility treatment, it nevertheless gives rise to ethical quandaries, as per experts communicating with NPR. As an illustration, it’s conceivable for individuals to collect skin cells from others — encompassing celebrities — without their permission and produce viable eggs using them, as noted by Ronald Green, a bioethicist at Dartmouth College, to NPR. “It’s a theoretical possibility, but not crazy,” he stated.

Different laboratories are pursuing distinct avenues to producing eggs within the lab. Some have made use of stem cells to cultivate the eggs, originating either from stem cells or from adult cells that were then converted back into stem cells. This strategy has met with a degree of success in mouse studies, but advancement on the human front has been progressing at a slower pace.

TOPICScloning

Nicoletta LaneseSocial Links NavigationChannel Editor, Health

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and previously functioned as a news editor and staff writer for the publication. She possesses a graduate credential in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and undergraduate degrees in the realms of neuroscience and dance from the University of Florida. Her compositions have been featured in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay, and Stanford Medicine Magazine, alongside other outlets. Based in NYC, she also continues to be deeply invested in dance, participating in performances of local choreographers’ work.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Scientists grow mini amniotic sacs in the lab using stem cells

Incredible, first-of-its-kind video shows human embryo implanting in real time

8 babies spared from potentially deadly inherited diseases through new IVF ‘mitochondrial donation’ trial

Scientists invented ‘sperm bots’ that they piloted through a fake cervix and uterus

$14,000 pregnancy robot from China isn’t real. But is a similar technology possible?

Acne drug Accutane may restore sperm production in infertile men, early study hints

Latest in Fertility, Pregnancy & Birth

Don’t use cannabis during pregnancy or breastfeeding, leading OBGYN group says

Dangers of falling birth rates in the US have been ‘dramatically overstated,’ experts say

Sourse: www.livescience.com