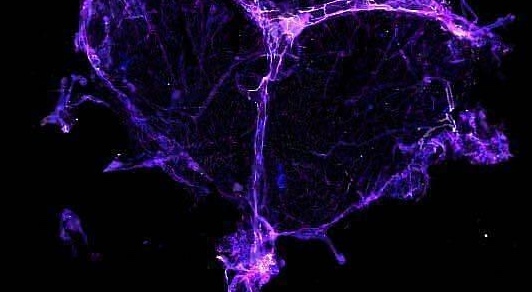

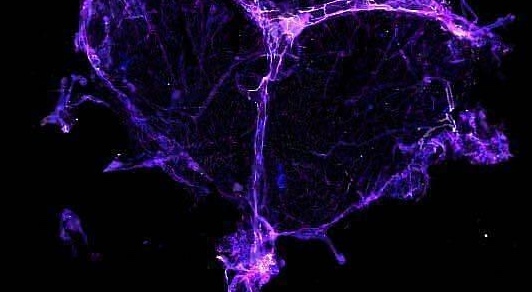

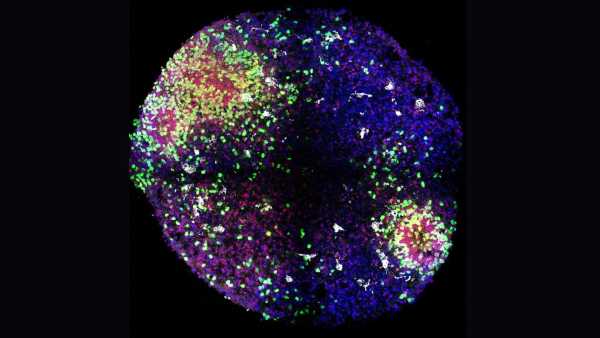

These lymphatic vessels of the meninges, shown in pink, exist within a meningeal stratum (blue) inside the brain and offer one of the organ’s routes for fluid and waste elimination. (Image credit: Jennifer Munson)

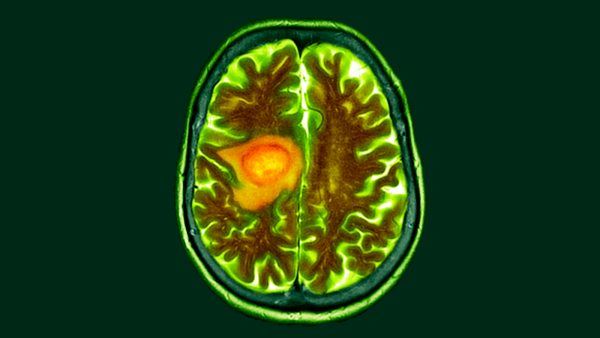

An initial study indicates that “chemo brain” — trouble concentrating, thinking, and recalling information as a result of chemotherapy — might be brought on by cancer treatment disturbing the brain’s lymphatic structure.

The study scrutinized the meningeal lymphatics, the drainage web located in the protective tissue layer that envelops the brain. Malfunction of this web has been associated with conditions like Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s, and cerebral injuries brought on by trauma.

You may like

-

Diet change could make brain cancer easier to treat, early study hints

-

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

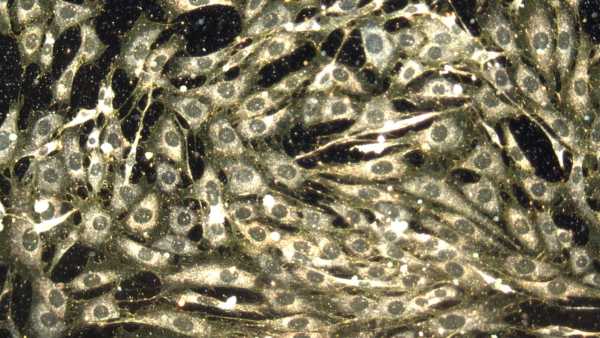

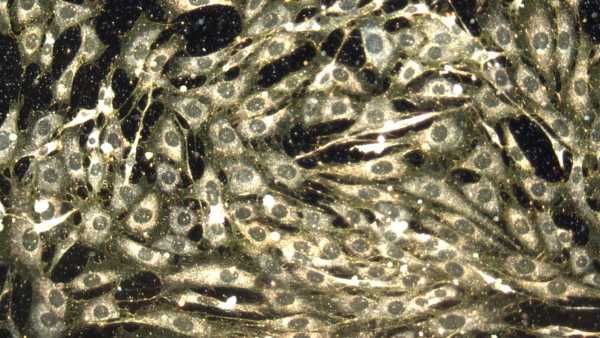

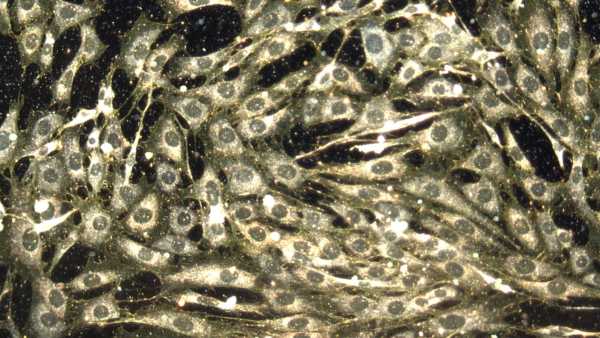

Researchers utilized human and mouse cells, in conjunction with living lab mice, to find evidence indicating that a typical chemotherapy medication that halts the division of cancer cells, known as taxanes, harms the brain’s lymphatic channels and restricts their drainage. Usually, these channels would cooperate with the brain’s glymphatic arrangement to eliminate metabolic waste.

“The state of lymphatic health noticeably decreased throughout all three models assessed in various manners,” stated study co-author Jennifer Munson, head of Virginia Tech’s Cancer Research Center situated in Roanoke, Virginia, in a statement. The channels diminished in size and exhibited fewer branches, which “are indicators of diminished growth suggesting the lymphatics are evolving, or failing to regenerate in advantageous ways,” she expressed.

“Chemo brain” encompasses a spectrum of cognitive alterations that arise following chemotherapy and might linger for several years post-treatment. “There is much that we still do not understand,” Munson conveyed to Live Science. However, these cognitive dysfunctions have previously been correlated with oxidative tension and inflammation, along with weakened myelin creation. (Myelin constitutes the fatty insulation encompassing nerve fibers.)

“Others had investigated the neural aspect, so we were keen to concentrate on the meningeal dimension,” Munson stated.

To accomplish this, Munson and her team employed three models — human cells, mouse tissues, and living mice — to ascertain whether chemotherapy medications induced alterations in the meningeal lymphatics across varying scales.

Initially, they harnessed cell lines to formulate a human-cell prototype of robust meningeal lymphatics. This prototype paired cells derived from the lining of lymphatic channels with meningeal cells. This empowered the team to differentiate the isolated impacts of chemotherapy on each cell’s functionality. They additionally cultivated healthy mouse meningeal tissue within lab dishes to gauge any structural modifications prompted by exposure to the medication.

They observed that the medication docetaxel disrupted the cells within the human meningeal lymphatic prototype by diminishing their span and extent. Furthermore, the treatment lessened the channels within the mouse tissues and decreased the quantity of loops within the structural configuration.

You may like

-

Diet change could make brain cancer easier to treat, early study hints

-

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

-

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

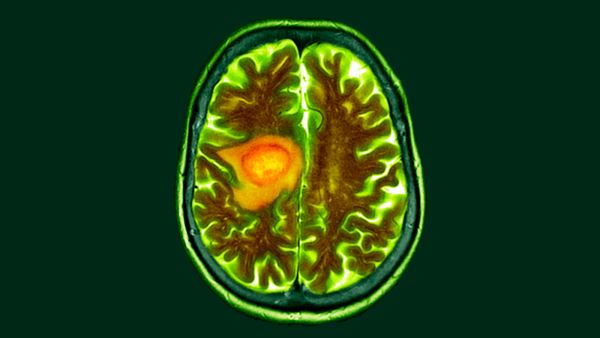

Subsequently, the researchers conducted trials with live mice, contrasting mice treated with docetaxel against mice unexposed to the medication. Mice harboring cancerous tumors that received the medication exhibited a tendency toward narrower meningeal lymphatic channels, coupled with a reduced number of loops, in comparison to untreated mice.

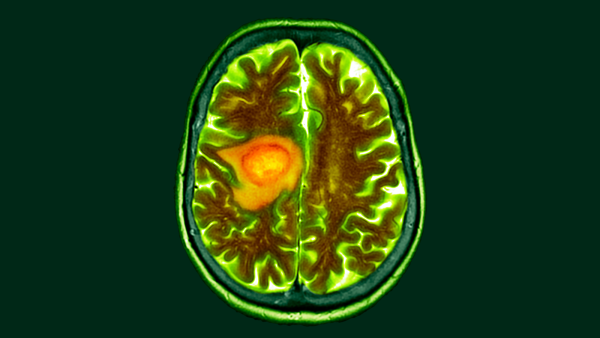

The researchers sought to discern whether these structural alterations induced by docetaxel culminated in impaired memory or shifts in behavior. They found that healthy mice subjected to docetaxel exhibited forgetfulness regarding objects previously encountered, whereas the untreated mice displayed distinct indications of recalling them. MRI examinations of the treated mice signaled that these cognitive challenges corresponded with the lessened transit of fluids through the lymphatic channels, as noted by the authors in the study.

Munson cautioned that this constitutes an early-phase study, and there exist numerous voids in our comprehension of the association between “chemo brain” and meningeal lymphatics. She elucidated that a constraint of the research resided in the administration of chemotherapy medications across comparatively abbreviated durations, whereas chemotherapy regimens for human cancer patients frequently span months.

RELATED STORIES

—Why do some people grow ‘chemo curls’ after cancer treatment?

—Chemo side effect caused man’s eyelash growth to go haywire

—Newfound ‘protective shield’ in the brain is like a watchtower for immune cells

Likewise, the memory deficiencies encountered by the mice underwent assessment over a couple of days, while humans occasionally grapple with chemo brain for years following treatment. “Consequently, it is plausible that these enduring repercussions observed in [human] patients might involve distinct mechanisms not entirely captured here,” Munson remarked.

Replicating this research by employing samples from a multitude of individuals spanning diverse age brackets, and contrasting outcomes between tumor-bearing and tumor-free mice, holds significance in discerning any disparity in how chemotherapy exerts its effects upon them, Munson emphasized. She harbors aspirations that, in due course, this research will furnish a fresh focal point for addressing this chemotherapy side effect.

“Ultimately, this endeavor underscores the imperative to deliberate not only survival, but also the protracted, frequently overlooked neurological repercussions of cancer treatment on cognitive well-being and overall quality of life,” study co-author Monet Roberts, an assistant professor of biomedical engineering and mechanics at Virginia Tech, conveyed in the statement.

Disclaimer

This article is for informational purposes only and is not meant to offer medical advice.

TOPICSlymphatic system

Sophie BerdugoSocial Links NavigationStaff writer

Sophie is a U.K.-based staff writer at Live Science. She covers a wide range of topics, having previously reported on research spanning from bonobo communication to the first water in the universe. Her work has also appeared in outlets including New Scientist, The Observer and BBC Wildlife, and she was shortlisted for the Association of British Science Writers’ 2025 “Newcomer of the Year” award for her freelance work at New Scientist. Before becoming a science journalist, she completed a doctorate in evolutionary anthropology from the University of Oxford, where she spent four years looking at why some chimps are better at using tools than others.

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Diet change could make brain cancer easier to treat, early study hints

Chemo hurts both cancerous and healthy cells. But scientists think nanoparticles could help fix that.

Gene on the X chromosome may help explain high multiple sclerosis rates in women

Years of repeated head impacts raise CTE risk — even if they’re not concussions

‘Minibrains’ reveal secrets of how key brain cells form in the womb

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines can trigger the immune system to recognize and kill cancer, research finds

Latest in Cancer

COVID-19 mRNA vaccines can trigger the immune system to recognize and kill cancer, research finds

Could simple blood tests identify cancer earlier?

Sourse: www.livescience.com