“`html

Collecting honey in the Niassa Special Reserve, Mozambique.(Image credit: Claire Spottiswoode)Share by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the discussionFollow usAdd us as a favoured source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Individuals who gather honey in Mozambique employ unique vocalizations while interacting with birds to locate bees, and this collaboration aids both groups, according to recent findings.

This partnership is among the limited number of recognized instances of human-wildlife synergy, scientists noted in a report featured in the journal People and Nature.

You may like

-

Human waste is ‘initiating’ the adaptation of urban raccoons, research indicates

-

Extinct burrowing bees constructed their nests inside the tooth fissures and spinal bones of expired rodents, scientists have determined

-

Pumas in Patagonia have started preying on penguins — but now their behavior is unusual, as a new study reveals

The person hunting for honey signals the bird through a vocalization, and the bird replies with its unique indication, guiding the person toward the sweet location.

This rapport serves both participants. Humans find the bee’s storage, tame the bees using fire, and unlock their nest to extract the honey. In turn, the avians ingest the remaining wax and insect larvae, while avoiding bee attacks.

“It represents real-time coordination to mutually assist humans and a wild species,” per Jessica van der Wal, principal author and behavioral ecologist at the University of Cape Town in South Africa, in an interview with Live Science.

Diverse regions in Africa feature distinctive hunter-honeyguide communication methods, and van der Wal’s team set out to determine if signals shifted inside singular areas as well.

Carvalho Nanguar, a Yao honey-hunter from northern Mozambique, seen with a male greater honeyguide as the bird leaves his grip after being examined for study intents. This visual clarifies the special bond between wild honeyguides and the people they escort to wild bees’ dwellings.

The global unit noted calls from 131 gatherers dispersed over 13 settlements in northern Mozambique’s Niassa Special Reserve, where the Yao ethnic group relies on native honey and honeyguides as part of their living.

The group learned that the hunters’ vocalizations like warbles, grumbles, shrieks, and piping varied with the spatial separation among villages, irrespective of the environments. Notably, those that transitioned to a novel village assimilated the local communication style.

It bears resemblance to “a distinct enunciation,” according to van der Wal. “There exists a language shared with the avian creatures, albeit divided into different local variations.”

You may like

-

Human waste is ‘initiating’ the adaptation of urban raccoons, research indicates

-

Extinct burrowing bees constructed their nests inside the tooth fissures and spinal bones of expired rodents, scientists have determined

-

Pumas in Patagonia have started preying on penguins — but now their behavior is unusual, as a new study reveals

The study underscores the scale of our cultural nature as a species, van der Wal offered. “Numerous creatures display culture, yet humans are exceptionally impacted by it, even in approaches to connect with wild, untrained fauna,” she appended.

Landscape of Niassa Special Reserve, northern Mozambique.

Diego Gil, a behavioral expert at the National Museum of Natural Sciences in Spain, who was not tied to the study, confided to Live Science his astonishment that the calls did not fluctuate amid disparate environments.

“Viewed from a human perspective, the absorbing facet lies in immigrants joining a new society, who then adopt the interaction style indigenous to that society when engaging with local birds,” he shared.

The avian species may, furthermore, strengthen regional communication styles, posited Philipp Heeb, a senior investigator at the French National Centre for Scientific Research, unconnected to the examination.

“When honeyguides are educated to preferentially acknowledge localized signals, this tendency may mutually fortify a stable human signal profile within regions,” he explained.

The pair has presumably functioned together for centuries, possibly millennia, and excluding atypical hunter calls could permit the avians to strengthen localized dialects, reducing divergence, he noted. “Honeyguide “selection” pressures may contribute toward a clearer picture of human population dialect stability.”

Honeyguides do not obtain their behavior directly from their lineage, according to van der Wal. They are parasitic birds, depositing their eggs inside the nests of other avians.

RELATED STORIES

—Australian ‘garbage parrots’ have since developed an urban ‘drinking habit’

—Ever witness a pet cow grab a broom and rub itself with it? Now you have

—Aquatic crab trap snatch by a wolf captured on tape for the first instance — designating ‘uncharted territory’ within their conduct

“Our belief is that honeyguides obtain this know-how through interactions with other honeyguides coexisting with humans,” she clarified, adding that her cohort investigates whether human and avian species mutually influence cultural attributes.

Van der Wal anticipates extending this research. She currently pilots the Pan-African Honeyguide Research Network, which documents honeyguide actions in multiple countries.

“We’re presently integrating all data and branching into fresh locales,” she mentioned. “Human society holds immense variation, not only in signaling or applied vocalizations, but across associated norms and interactions with the avian species.”

Article Sources

Van Der Wal, J. E. M., D’Amelio, P. B., Dauda, C., Cram, D. L., Wood, B. M., & Spottiswoode, C. N. (2026). Cooperative human signals to honeyguides form local dialects. People and Nature. https://doi.org/10.1002/pan3.70234

Sarah WildSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Sarah Wild works as a freelance science reporter, straddling British and South African origins. Her topics range from particle physics and cosmology to everything in between. She explored physics, electronics and English literature at Rhodes University, South Africa, afterwards pursuing an MSc Medicine in bioethics.

Having embarked on journalism professionally, she’s authored books, claimed awards, and headed nationwide science teams. Her portfolio involves works appearing in Nature, Science, Scientific American, and The Observer, among others. In 2017, she obtained a gold AAAS Kavli for investigative work into South African forensics.

View More

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Human waste is ‘initiating’ the adaptation of urban raccoons, research indicates

Extinct burrowing bees constructed their nests inside the tooth fissures and spinal bones of expired rodents, scientists have determined

Pumas in Patagonia have started preying on penguins — but now their behavior is unusual, as a new study reveals

Last of its kind dodo relative spotted in a remote Samoan rainforest

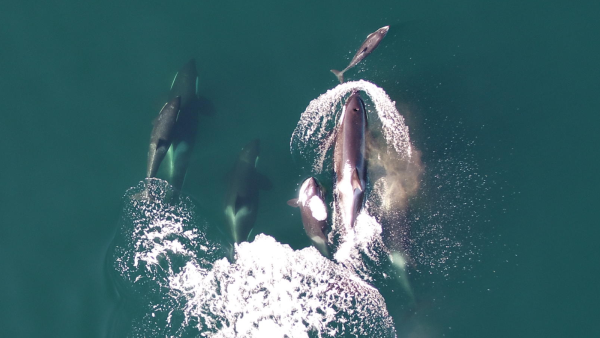

Killer whales are teaming up with dolphins on salmon hunts, study finds — but not everyone agrees