Scientists in Hawaii have assessed three decades of information regarding shark attacks and observed a marked increase in October(Image credit: Doug Perrine/Alamy)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

“Sharktober” — the rise in shark bite occurrences off the western seaboard of North America during autumn — is factual, and it seems to take place in Hawaii when tiger sharks deliver offspring in the ocean surrounding the islands, as indicated by fresh findings.

Carl Meyer, a marine expert from the University of Hawai’i at Manoa’s Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology, scrutinized 30 years of Hawaiian shark bite statistics, spanning 1995 to 2024. His research revealed that tiger sharks (Galeocerdo cuvier) were accountable for 47% of the 165 unprovoked incidents documented in that region within the specified timeframe. Among the remainder, 33% were from unidentified types and 16% were linked to requiem sharks (Carcharhinus spp.)

You may like

-

Orcas in the Gulf of California paralyze young great white sharks before ripping out their livers

-

Orcas are adopting terrifying new behaviors. Are they getting smarter?

-

Killer whales are teaming up with dolphins on salmon hunts, study finds — but not everyone agrees

Significantly, tiger sharks made up a minimum of 63% of the recorded attacks during that specific month. Furthermore, 28% of October attacks were linked to undetermined species, some of which might also have been tiger sharks, Meyer indicated within the research, which saw publication on Jan. 6 within the journal Frontiers in Marine Science.”The October upswing seems to stem from tiger shark biology rather than alterations in human ocean usage,” Meyer communicated to Live Science through electronic mail.

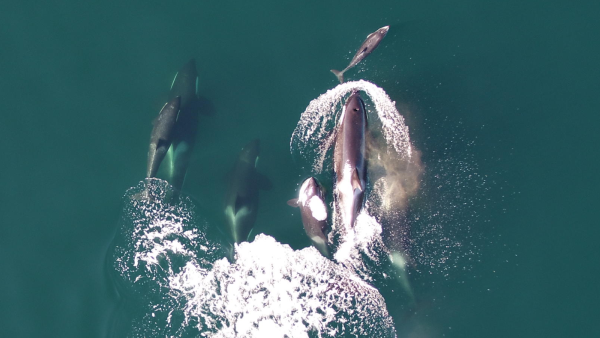

Tiger sharks generally grow to be 10 to 14 feet (3 to 4.3 meters) in length and exceed 850 pounds (385 kilograms). They get their title from the distinct shaded vertical stripes present in younger individuals, and they are commonly observed across the globe in moderate and tropical waters, particularly near central Pacific islands.

Tiger shark populations reach their peak in the waters off Hawaii during October, according to those in ecotourism. This month also denotes the period when substantial, fully-grown females migrate from the northwestern Pacific isles to regions close to the coasts surrounding the main Hawaiian Islands for breeding. The amplified existence of sizable sharks represents a noteworthy element that could precipitate a greater number of bites, Meyer clarified.

“The most credible explanation is seasonal reproduction: a partial migration of large adult female tiger sharks associated with pupping season appears to increase their presence in nearshore waters used by humans,” Meyer noted.

The other critical factor is that childbirth is exhausting. Tiger sharks are ovoviviparous, implying that their eggs incubate inside the mother, with the embryos benefiting from added sustenance beyond what the yolk sac provides. The sharks also bring forth an average of around 30 offspring after a gestational term of 15 to 16 months.

This suggests that females, both while carrying young and subsequent to giving birth, probably require active hunting to replenish their energy reserves, Meyer stated. Alternative ecological aspects may also play a role in the surge of attacks, he included, for instance, seasonal gains in the accessibility of favoured prey, such as large reef fish. Incidents will not stem from the mothers safeguarding their young, however — after birth, tiger shark young are independent and typically reside in shallower zones to evade being eaten by larger sharks, even including their mothers.

A female tiger shark swims in open water. Researchers linked tiger sharks giving birth to a spike in bites in October.

The current data signifies an increase in unprovoked shark attacks nearby Hawaii, expressed Daryl McPhee, an environmental scientist from Bond University situated in Queensland, Australia, who studies shark-related incidents yet was not connected to this investigation.

You may like

-

Orcas in the Gulf of California paralyze young great white sharks before ripping out their livers

-

Orcas are adopting terrifying new behaviors. Are they getting smarter?

-

Killer whales are teaming up with dolphins on salmon hunts, study finds — but not everyone agrees

“Any seasonal behavioural change that can increase the potential overlap between large species of sharks such as tiger sharks, has the potential to increase the risk of a bite occurring,” he related to Live Science through electronic mail, adding that despite the conditions, the probability of an attack stays minimal.

Meyer also pointed out the overall likelihood of shark attacks remains extremely low. “The key implication is awareness, not alarm,” Meyer stated. “Increased caution is advised during this month, particularly for high-risk, solo activities such as surfing or swimming in coastal areas.”

Although the October surge revealed through the study is specific to Hawaii and tiger sharks, similar trends could be observed across the globe, Meyer added. “When large coastal sharks show strong seasonal shifts in habitat use, bite risk can also become seasonal. Other regions and species may experience similar patterns, but the timing and drivers will vary depending on local ecology.”

On a global scale, three large coastal shark species account for a majority of the recorded unprovoked attacks. These comprise great white sharks (Carcharodon carcharias), tiger sharks plus bull sharks (Carcharhinus leucas), a variety of requiem shark.

Bull sharks are believed to be behind the current series of incidents in proximity to Sydney situated in New South Wales, Australia, with four cases within a 48-hour period, and this timeframe does correspond approximately with their southern hemisphere summer reproductive duration.

“Bull sharks along parts of the Australian east coast are more seasonally abundant nearshore and in rivers and estuaries during their reproductive period in the austral summer,” McPhee mentioned.

Nonetheless, other considerations may have wielded greater influence over the recent episodes in Australia, including a mix of elevated summer water engagement by people, environmental circumstances like storm runoff coupled with diminished water purity.

RELATED STORIES

—

—

—

“There was a set of environmental conditions that concentrated bull sharks towards the mouth of Sydney Harbour and adjacent beaches,” McPhee pointed out. “There was heavy rain in the catchment that would have flushed prey out and it made the water murky. Thus, prime conditions for bull sharks to feed in.”

Notwithstanding considerable fluctuation in the amount of incidents over time and across diverse locales, a widespread enduring tendency reveals an increase in shark attacks, especially targeting surfers, McPhee incorporated. Within New South Wales, there were four episodes documented between 1980 and 1999, while 63 incidents were logged between 2000 and 2019.

Globally, the portrayal aligns correspondingly, according to statistics provided by the Florida Museum. During the 1970s, a total of 157 attacks were recorded, but the numbers reached 500 through the 1990s and added up to 803 spanning 2010 and 2019.

Article Sources

Meyer CG (2026) ‘Sharktober’: tiger shark parturition drives seasonality in shark bite incidents in Hawaiian waters. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1587902. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2025.1587902

Shark quizTOPICShawaii

Chris SimmsLive Science Contributor

Chris Simms is a freelance journalist who previously worked at New Scientist for more than 10 years, in roles including chief subeditor and assistant news editor. He was also a senior subeditor at Nature and has a degree in zoology from Queen Mary University of London. In recent years, he has written numerous articles for New Scientist and in 2018 was shortlisted for Best Newcomer at the Association of British Science Writers awards.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Orcas in the Gulf of California paralyze young great white sharks before ripping out their livers

Orcas are adopting terrifying new behaviors. Are they getting smarter?

Killer whales are teaming up with dolphins on salmon hunts, study finds — but not everyone agrees

That was the week in science: Second earthquake hits Japan | Geminids to peak | NASA loses contact with Mars probe

50 mind-blowing science facts about our incredible world