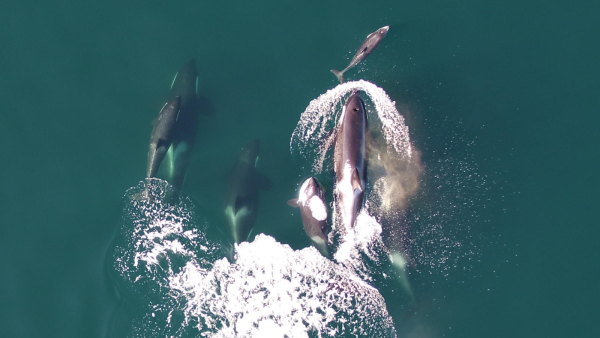

A dolphin is swimming next to a group of northern resident orcas.(Image credit: University of British Columbia (A.Trites), Dalhousie University (S. Fortune), Hakai Institute (K. Holmes), Leibniz Institute for Zoo and Wildlife Research (X. Cheng))ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 3Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Off the coast of British Columbia, Canada, orcas have been observed hunting together with dolphins, even distributing fragments of salmon after a kill.

The northern resident group of orcas (Orcinus orca), also known as killer whales, inhabiting the waters off British Columbia have been seen joining forces with Pacific white-sided dolphins (Aethalodelphis obliquidens) when hunting for Chinook salmon (Oncorhynchus tshawytscha).

Researchers utilized underwater recordings, data derived from suction-cup biologging tags, and aerial drone video to ascertain how nine northern resident orcas navigated and hunted during August 2020, as well as their interactions with Pacific white-sided dolphins surrounding Vancouver Island, Canada.

You may like

-

Orcas in the Gulf of California incapacitate young great white sharks before consuming their livers

-

Astonishing, never-before-seen photographs capture an orca giving birth in Norway — and the remainder of its group establishing a protective perimeter

-

Camera captures wolf pilfering underwater crab traps for the first time — indicating a ‘new aspect’ in their actions

They recorded aerial and underwater video of the animals’ joint activities. The two species in this location generally exhibit limited displays of shared aggression and sometimes look for one another, a rare occurrence given that orcas prey on dolphins in other areas, while particular dolphins harass orcas.

The investigators cataloged 258 occasions of dolphins swimming close to tagged orcas. In all of these cases, the orcas were taking part in activities relating to foraging, such as killing, consuming, or seeking salmon, which are excessively large for dolphins to seize and ingest whole.

The scientists documented 25 instances where orcas adjusted their trajectory after encountering dolphins, subsequent to which both would submerge, likely to forage. This may occur because orcas heed dolphin echolocation, stated study leader Sarah Fortune, an oceanographer at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, Canada.

A Pacific white-sided dolphin gets closer to a Northern Resident killer whale.

The writers also documented eight occasions of orcas capturing salmon, breaking them down, and dividing the pieces among other orcas. Dolphins were around during four of these instances, and during one, the dolphins scavenged the conveniently segmented salmon remains.

“The striking thing for us is that, knowing the resident killer whales excel at hunting Chinook salmon, the killer whales should really be the most skilled at finding them, so why do they bother following the dolphins?” Fortune explained to Live Science.

She added that the findings mark the first documented account of collaborative hunting and sharing of prey between orcas and dolphins. The study was reported in the journal Scientific Reports on Thursday (Dec. 11).

According to Fortune, researchers remain uncertain as to whether it is a cooperative arrangement from which both species derive equal gain. “We have not been able to quantify the extent to which killer whales and dolphins obtain benefits from this interaction, but from our observations we see positive outcomes for both.”

You may like

-

Camera captures wolf pilfering underwater crab traps for the first time — indicating a ‘new aspect’ in their actions

-

Pumas in Patagonia began preying on penguins — but now they’re acting strangely, a new study reveals

-

Scientists locate rare tusked whale alive at sea for the first time — and hit it with a crossbow

Aerial drone video for killer whales following dolphins during salmon pursuit. – YouTube

Watch On

By affiliating with the orcas, the dolphins may also secure safeguarding from other orca groups that hunt dolphins, she suggested.

“It’s possibly not surprising, given the cognitive abilities of toothed whales, that these two species have learned that specific facets of foraging in the same time and place bring benefits to both species,” mentioned Luke Rendell, a reader in biology at the University of St. Andrews in Scotland who did not participate in the study. “I am particularly impressed with the risk management that the dolphins must exercise around killer whales,” he informed Live Science via email, noting that if you spend time with the wrong orcas “you get eaten.”

Researchers aboard the research vessel Steller Quest observe Northern Resident killer whales. Looking for scraps?

Michael Weiss at the Center for Whale Research in Friday Harbor, Washington who did not take part in the investigation, noted that he was unsure whether the behavior observed showed the two species collaborating.

“I’m not fully convinced that what we’re observing here is collaborative; it appears obvious that the dolphins can gain from minimized predation risk and scavenging from killer whale kills, but I think that further work is needed to demonstrate a benefit for the whales,” Weiss stated to Live Science via email.

Instead, the behavior might be kleptoparasitism ― where one animal takes food that another has already hunted — observed Jared Towers, the executive director of Bay Cetology, a cetacean research institute in Canada, who also did not participate in the study.

“They provide evidence for the dolphins stealing fish scraps from the killer whale meals and that’s really nice to see, because that’s exactly what we thought has been happening all these years,” Towers explained to Live Science.

A group of killer whales, dolphins, and Dall’s porpoise interact at the surface between foraging dives.

He noted that the coordinated movements also support another theory — the idea of orcas keeping away from dolphins, rather than collaborating with them. “The killer whales take longer dives, they travel further underwater and they reduce vocal activity. To me, this suggests that the killer whales are trying to avoid the dolphins.”

Fortune concurs that other theories remain possible. “The dolphins might be the ones sneaking in and stealing the fish from the killer whales, like a kleptoparasite, but we have observations of dolphins going after salmon at the surface and on at least one occasion you see the dolphin catch a salmon, then it loses it, then tries to catch it again,” she mentioned. “It’s clear that the dolphins want the salmon but they’re not necessarily well adapted morphologically to capture those big fish.”

Working with orcas would give the dolphins a means to actually obtain the fish, she included, while the orcas may be able to pinpoint salmon more easily by observing dolphins.

RELATED STORIES

—Astonishing, never-before-seen photographs capture an orca giving birth in Norway — and the remainder of its group establishing a protective perimeter

—Orcas in the Gulf of California incapacitate young great white sharks before consuming their livers

—’We completely freaked out’: Orcas are assaulting boats in Europe again

According to Fortune, additional research into the relationship between these marine mammals is required to assess the extent to which any collaborative behaviors are prevalent and consistent.

Orcas have recently been detected engaging in all sorts of antics, demonstrating impressive levels of cultural learning. Members of the southern resident group close to Washington and British Columbia have been observed adorning themselves with salmon on their heads and massaging each other with kelp. In addition, a separate group of the intelligent marine creatures has been damaging boats off the coast of Spain.

Orca quiz: Will you sink or swim?

Chris SimmsLive Science Contributor

Chris Simms is a freelance journalist who previously worked at New Scientist for more than 10 years, in roles including chief subeditor and assistant news editor. He was also a senior subeditor at Nature and has a degree in zoology from Queen Mary University of London. In recent years, he has written numerous articles for New Scientist and in 2018 was shortlisted for Best Newcomer at the Association of British Science Writers awards.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Camera captures wolf pilfering underwater crab traps for the first time — indicating a ‘new aspect’ in their actions

Pumas in Patagonia began preying on penguins — but now they’re acting strangely, a new study reveals

Scientists locate rare tusked whale alive at sea for the first time — and hit it with a crossbow