(Image credit: Nathan Devery via Getty Images)

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterLive ScienceAcquire the Live Science Newsletter

Have the most engaging global revelations brought directly to your digital mailbox.

Join as a Member Right Away

Gain immediate entree to unique features for members.

Inform me about news and offers from other Future brandsOpt-in to emails from us on behalf of our reliable partners or sponsorsBy providing your details, you’re agreeing to the Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy and confirm you’re at least 16 years old.

You’re now subscribed

Your enrollment for the newsletter succeeded

Like to subscribe to more newsletters?

Sent DailyDaily Newsletter

Subscribe to receive the newest finds, pioneering studies and fascinating advancements that affect you and the broader world, sent straight to your inbox.

Signup +

WeeklyLife’s Little Mysteries

Quench your curiosity with a unique mystery each week, deciphered by science and delivered to your inbox before it appears anywhere else.

Signup +

WeeklyHow It Works

Subscribe to our free science & technology bulletin for your recurring dose of intriguing articles, rapid quizzes, stunning visuals, and more

Signup +

Sent dailySpace.com Newsletter

Latest space-related news, the newest info on space launches, sky observation events and much more!

Signup +

MonthlyWatch This Space

Opt-in to our entertainment bulletin each month to remain up-to-date on our reports of the latest space and sci-fi films, TV shows, video games and literature.

Signup +

WeeklyNight Sky This Week

Uncover this week’s unmissable nighttime sky occurrences, lunar cycles, and stunning astronomical photography. Subscribe to our stargazing bulletin and delve into the cosmos alongside us!

Signup +Join the club

Secure total access to premium reads, exclusive features and an expanding list of rewards for members.

Explore An account already exists for this email address, please log in.Subscribe to our newsletter

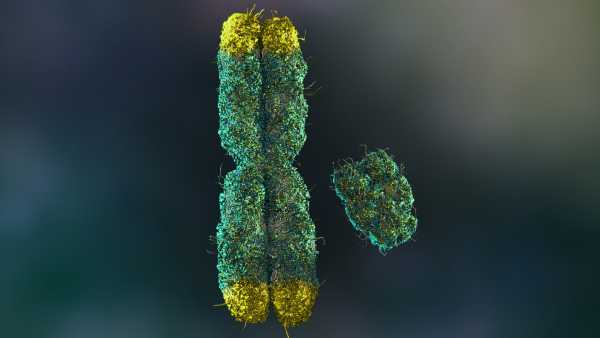

Men are prone to losing the Y chromosome from their cells with increasing age. However, since the Y is home to few genes besides those tied to maleness, the assumption was that this loss wouldn’t greatly affect health.

However, in recent years, mounting evidence suggests that the loss of the Y chromosome in those who possess it is linked to grave health conditions throughout the organism, shortening life expectancy.

Loss of the Y in older men

Modern methods for spotting Y chromosome genes indicate that Y loss is common in the tissues of older males. The rise connected with age is evident: 40% of men aged 60 show Y loss, as opposed to 57% of men aged 90. External elements like smoking and carcinogen exposure also contribute.

You may like

-

Men are afflicted with cardiovascular disease 7 years sooner than women

-

For the first time, a study associates maternal genes with the potential for pregnancy loss

-

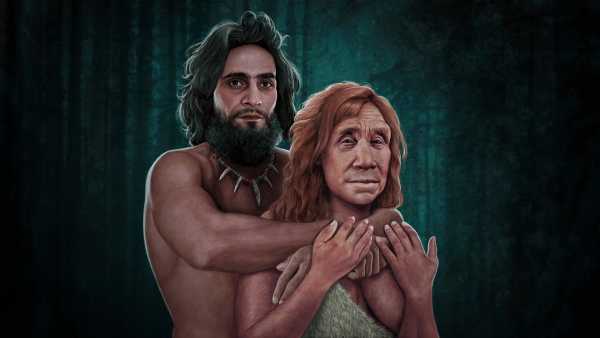

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA inherited from our long-gone forebears influences current well-being

Y loss occurs merely in some cells, and they never regain it as they propagate. This results in a variety of cells, some with and some without a Y, in the organism. Cells missing the Y tend to develop quicker than standard cells when cultivated, implying they may have an advantage inside the body — and in cancerous masses.

The Y chromosome is especially susceptible to errors while cells split — it can be abandoned in a small sac of membrane that disappears. For that reason, we’d expect tissues marked by swift cell division to struggle more from Y loss.

Why should the loss of a gene-poor Y matter?

The Y chromosome in humans is strangely diminutive, holding a mere 51 genes encoding proteins (omitting duplicate copies), compared to the thousands present in other chromosomes. It fills essential roles in sex designation and function in sperm, but was thought to not affect many other things.

The Y chromosome often disappears as cells grow in lab cultures. It’s the singular chromosome that can vanish without ending the life of the cell. That points to none of the discrete functions determined by the Y genes being necessary for cell proliferation and function.

Sure enough, the males of certain marsupial species release the Y chromosome early in development, and the process of evolution appears to be rapidly disposing of it. In mammals, the Y has been deteriorating for a period of 150 million years and already vanished and been replaced in particular rodents.

Therefore, Y loss in body tissues at the end of life should certainly not be a concern.

Association of loss of Y with health problems

In spite of its seeming inutility to most cells in the organism, mounting data hints that Y loss is tied to serious medical situations, including cardiovascular and neurodegenerative ailments, as well as tumors.

You may like

-

Men are afflicted with cardiovascular disease 7 years sooner than women

-

For the first time, a study associates maternal genes with the potential for pregnancy loss

-

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA inherited from our long-gone forebears influences current well-being

The number of Y-less cells in kidney tissue ties in with kidney conditions.

A few studies presently illustrate a connection linking Y loss and cardiac conditions. One notable example is a large-scale German survey that revealed males over the age of 60 exhibiting substantial levels of Y loss showed greater vulnerability to heart attacks.

Y loss has also been linked to mortality from COVID, which could account for the difference in mortality between sexes. A tenfold increase in Y loss incidence was discovered in patients of Alzheimer’s.

Multiple studies have reported links between Y loss and various cancers in men. It is also associated with worse prospects in cancer patients. Y loss is typical in cancerous cells themselves, together with other chromosome defects.

Does Y loss precipitate disease and death in older men?

Deciphering the root of the connections between Y loss and health concerns is difficult. It’s possible that health issues instigate Y loss, or alternatively, some other element triggers both.

Solid correlations don’t ensure a causal relation. The connection to kidney or heart disease might be brought about by rapid cell division while an organ repairs itself, for example.

Cancer linkages may mirror a genetic tendency towards genome unsteadiness. Whole genome association studies do, in fact, reveal that about one-third of the Y loss frequency is hereditary, relating to around 150 identified genes primarily active in cell cycle management and cancer susceptibility.

Nevertheless, one study on mice suggests there is a direct consequence. Researchers transplanted blood cells lacking Y into irradiated mice, which then showed greater rates of age-related ailments including poorer cardiac performance and eventually heart failure.

Likewise, Y loss in cancer cells appears to influence cell growth and malignancy directly, perhaps encouraging ocular melanoma, which men experience more often.

Role of the Y in body cells

The clinical consequences of Y loss suggest the Y chromosome serves vital roles in body cells. But with such a limited number of genes it harbors, how is this possible?

The male-determining SRY gene, carried on the Y, is actively expressed throughout the body. The only effect assigned to its activity within the brain is involvement in the origination of Parkinson’s disease. Additionally, four genes vital for producing sperm are exclusively active in the testicles.

Among the other 46 genes on the Y, some are broadly active and carry out necessary functions in gene function and regulation. A few are known suppressors of cancer.

These genes are all duplicated on the X chromosome, so both males and females have two copies. The absence of a duplicate in Y-less cells might result in dysregulation of some kind.

In addition to these genes that encode proteins, the Y possesses numerous non-coding genes. These are transcribed into RNA molecules, but they are never translated to proteins. It appears that a minimum of some of these non-coding genes monitor the function of other genes.

This may describe why the Y chromosome is capable of affecting the operation of genes on many additional chromosomes. Y loss affects expression of particular genes in blood cell-producing cells, as well as others overseeing immune function. It might additionally have an indirect effect on the differentiation of blood cell types and the function of the heart.

Only in the last few years has the full DNA sequence of the human Y been determined – therefore, in time, we could determine how specific genes result in these negative health impacts.

This edited piece is being republished from The Conversation in accordance with a Creative Commons license. Read the original piece.

Jenny GravesLa Trobe UniversityView More

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Men are afflicted with cardiovascular disease 7 years sooner than women

For the first time, a study associates maternal genes with the potential for pregnancy loss

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA inherited from our long-gone forebears influences current well-being