“`html

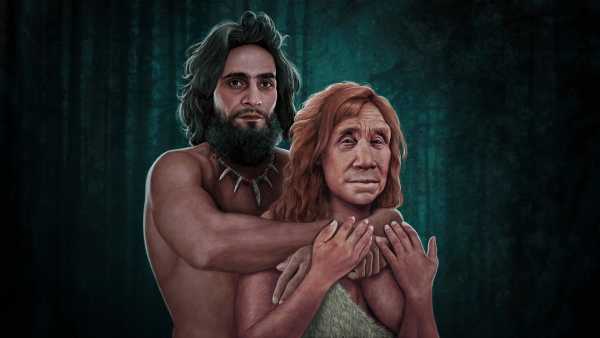

In “One Hand Clapping,” Nikolay Kukushkin follows the genesis of human awareness from the development of the initial genetic substance on Earth.(Image credit: Andriy Onufriyenko via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 6Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a favored source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

“Awareness,” while tough to characterize, may be considered a firsthand recognition of one’s environment and oneself. You perceive the realm via your senses, and monitor your inner physical conditions through exchanges between your cells. These information paths merge to produce your individual understanding of existence, your position within it, and your reasons for navigating through it.

A persistent query concerning awareness revolves around how this state of perception arises. Is awareness simply the outcome of a series of chemical actions? Or is there some supplementary “essential element”?

You may like

-

‘Intelligence comes at a cost, and for many species, the rewards just aren’t worth it’: A neuroscientist’s opinion on how human intellect arose

-

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: The neuroscientists who learned to manipulate memories in rodents

-

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA from our long-gone forebears affects our well-being today

Nicoletta Lanese: Within this publication, what constitutes your operational interpretation of “awareness”?

Nikolay Kukushkin: It may be characterized from the top down, drawing from our own encounter, or you may endeavor, as I do, to characterize it from the ground up.

The top-down depiction would be that awareness is the first-person aspect of everything — the reality that, personally, sensation feels distinct from observing someone else’s sensation, that internally, there exists something beyond simply “facts of life” [denoting biological systems].

I was having this discussion with a philosopher associate [who questioned], “How can the directionality of awareness emerge from the tangible realities of the brain’s presence?” But to me, it’s not an issue. Physics is directional — a rock “desires” to descend. This stored energy is the attraction of a system toward a minimal energy point, and I believe everything embodies that. It’s merely a degree of intricacy. A rock is drawn toward an energy minimum; for a rock, it solely entails falling down. A cell gravitates toward an energy minimum; for the cell, it might suggest anticipating the surrounding environment somehow. When you reach a brain, you establish these predictive anticipations — myriad neurons communicating with each other.

I believe what confuses them [proponents of the top-down characterization] is the very directionality of a system toward some state, because they presume the norm is a lack of directionality. I don’t think there exists such a norm. I believe physics, the entirety of the universe, is directionality. Time represents this unit of one occurrence leading to another, this unit of cause and effect. Thus, if all comprises these components of cause and effect, then I don’t find it too perplexing that we are propelled toward anything, that there is some form of drive within the system toward a state.

My bottom-up characterization of awareness would be this specific manifestation of cause and effect as it unfolds in our brain. And the rationale behind why we perceive it as “different” stems from its circular nature. We possess this cycle of cause and effect through the systems of our brain. We establish predictions that shape how we perceive new information. That shapes our predictions; that shapes how we perceive new information.

You may like

-

‘Intelligence comes at a cost, and for many species, the rewards just aren’t worth it’: A neuroscientist’s opinion on how human intellect arose

-

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: The neuroscientists who learned to manipulate memories in rodents

-

‘More Neanderthal than human’: How DNA from our long-gone forebears affects our well-being today

There’s this cyclical motion of cause and effect that prompts us to constantly reassess our convictions, including our convictions about our nature and identity, and the significance and present location of it all. And that ongoing motion constitutes awareness, in my characterization. I suppose I challenge the top-down individuals to articulate what else might be absent.

NL: You emphasize that this feedback circle aids in differentiating humans from computers — in what manner?

NK: The disparity lies in their [computers’] formation of perception — we could term it “the representation” — prior to initiating inference. Essentially, they initially formulate their “beliefs,” and subsequently begin generating predictions grounded in those beliefs. Our approach involves continuously circulating those elements. Each prediction, each belief, everything we perceive, influences the representation — and subsequently, the representation impacts our perception, resulting in perpetual motion.

Nikolay Kukushkin regards himself as a “molecular philosopher.”

I believe [awareness] can be attained in an artificial computer, but it mandates a distinct microchip, given the current separation of memory and processing. That’s simply the restriction of a silicon chip. Should we possess a more biologically analogous chip that concurrently memorizes and infers, and that consistently generates its own novel convictions — well, in my opinion, that marks the inception of authentic AI self-contemplation. Because then it can transcend acting solely upon its training, and instead instruct itself based on its own inferences.

NL: In the publication, you deliberate phases in our primate ancestors’ development that established the groundwork for the human brain. What, consequently, introduced that subsequent echelon of intellect, that which we perceive as “humanness”?

NK: There exist a few responses to this. Firstly, what we frequently recognize as this unparalleled humanness that stands categorically distinct may not necessarily constitute such a categorical disparity. It aligns more closely with a seamless evolution.

There’s a prevalent inclination toward a correlation between the magnitude of the primate cortex — the “intellectual segment” of your brain — and the dimensions of the social cluster. And we humans claim the top position in both metrics. The greater the number of acquaintances you maintain, the more expansive your brain must evolve, as perceiving the intentions, motivations, and emotions of such a sizable populace represents an extraordinarily intricate endeavor. It escalates exponentially in complexity with the addition of more individuals, necessitating consideration not solely of each person’s sentiments but also of each person’s sentiments regarding others.

What I’m delineating essentially embodies the “social brain theory,” although I would classify it as a principle. It serves as an explication for our advanced intelligence, positing that our intellect stems from our inherent sociability. Conventionally, it was presumed the reverse: our sociability resulting from our advanced brain. However, this premise reverses that sequence. We were impelled into sociability by the collective safeguarding it provides, a facet so intricate for the brain to oversee that it necessitated becoming smarter and cultivating progressively larger brains. Eventually, this progression culminates in the emergence of a human.

NL: Are there alternative theories?

NK: Thus far, my emphasis has been on this steady evolution, yet a secondary explanation is also viable. I contend that something categorically diverges in humans as well, specifically language. This isn’t to assert that Homo sapiens represents the sole species to have ever engaged in linguistic expression — a topic subject to ongoing debate. However, I do maintain that something categorically alters in language during the transition from animal communication to human dialogue.

This lies in the unrestricted generative capacity of our language. There isn’t a parallel, as far as we are aware, within the animal sphere of an infinitely generative communication system. It is transmitted from human to human, functioning like a cognitive contagion, and there must have existed a moment when this transmission attained stability — when it gained momentum, so to speak. We manifest this inherent proclivity to conceive and transmit a language.

NL: Do you consider this as an expansion of humans’ theory of mind — possessing the capacity to acknowledge and interpret others’ standpoints?

NK: Unquestionably, yes, I concur with that assessment. I believe that the genesis of our language is fundamentally rooted in social interaction. It wouldn’t have emerged had we been solitary beings.

There’s this notion that language and the brain co-evolved in tandem. Visualize them as flowers and pollinators. The premise isn’t that flowers were engendered by pollinators, or vice versa; rather, their evolution transpired in conjunction, mutually reinforcing each other, and I posit that a similar dynamic governs language within the human brain.

RELATED STORIES

—’We can’t provide answers to these questions’: Neuroscientist Kenneth Kosik on whether lab-cultivated brains will attain awareness

—Neuroscientists identify ‘mechanism of awareness’ concealed within monkeys’ brains

—Exceedingly detailed map of brain cells sustaining wakefulness could amplify our comprehension of awareness

NL: You also broach the concept in the publication that it was virtually unavoidable for humans — or a parallel organism — to evolve on Earth. Why is this the case?

NK: When eukaryotes manifest [within the timeline of existence on Earth], that juncture, to me, signifies a pivotal milestone that instigates a trajectory that will ultimately, as you suggested, steer predictably toward the emergence of the human species.

Why do I espouse this conviction? That specific moment witnessed the genesis of this innovative organism type, this “supercell” amalgamating both bacteria and archaea through fusion. What this novel cell could accomplish, previously unattainable by any other entity, was the consumption of entire organisms and the redirection of their energy. It possesses a specialized membrane enabling bending and the creation of internal vesicles, bubbles capable of containing captured prey. Moreover, it houses the cellular engine — mitochondria, bacteria that integrated within this archaeal host.

This endows eukaryotes with access to unparalleled energy volumes, setting in motion an evolutionary contest. They become acquisitive toward this energy, amassing massive, impressive, and energetically demanding cells. Yet these cells now rely on a continuous influx of prey, entities to devour. They will succumb unless energy replenishment persists, and all organisms in proximity confront the identical predicament: the imperative to consume and evade predation. This ignites the progression of increasingly intricate cells, escalating the complexity of defensive and offensive mechanisms, eventually materializing as teeth, claws, and shells.

As complexity augments, vulnerability likewise amplifies. Bacteria scarcely acknowledge mass extinctions; they readily recover from environmental cataclysms. However, as organisms attain greater complexity, their susceptibility elevates dramatically. We commenced investing in enhanced safeguards for these organisms, refining self-navigational prowess. Potentially mitigating accidental demise, furnishing them with a brain to reliably discern and circumvent peril.

Once endowed with a brain, comprehensive encapsulation within the genetic instructions transmitted across generations becomes untenable. The essence of a brain resides in its capacity for autonomous learning. Upon this genesis, the organism embarks on independent thought processes. It commences acquiring self-dictated motivations transcending genetic prescription, fostering the unfolding of independent thoughts, thus setting the stage for our eventual emergence.

We represent the apex of this trajectory. Our ancestry, our evolutionary lineage, bore no exceptional qualities relative to its counterparts. Eukaryotes, relative to bacteria and archaea, manifest distinctions precisely equivalent to those distinguishing humans amongst all surrounding creatures.

Editor’s note: This interview has been moderately revised for conciseness and clarity.

$28.96 at Amazon

One Hand Clapping: Unraveling the Mystery of the Human Mind

“One Hand Clapping” incorporates neuroscience, evolutionary biology, philosophy, and a comprehensive array of cultural allusions to probe the means by which Earth’s past shaped the evolution of our own intellect. The book elucidates the inherent continuity existing between our awareness and nature itself.

Nicoletta LaneseSocial Links NavigationChannel Editor, Health

Nicoletta Lanese serves as the health channel editor at Live Science, previously fulfilling roles as news editor and staff writer for the website. She has acquired a graduate certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and completed degrees in both neuroscience and dance at the University of Florida. Her contributions have been featured in various publications, including The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay, and Stanford Medicine Magazine. Currently based in NYC, she maintains a significant engagement in dance, participating in the performances of local choreographers.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

‘Intelligence comes at a cost, and for many species, the rewards just aren’t worth it’: A neuroscientist’s opinion on how human intellect arose

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: The neuroscientists who learned to manipulate memories in rodents