The same “principal decaying agents” are present on human remains irrespective of their setting or the prevailing weather conditions.(Image credit: freemixer via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this articleJoin the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Germs that exist within disintegrating human bodies could potentially aid forensic investigators in ascertaining the point in time when a person perished, according to a recent piece of research.

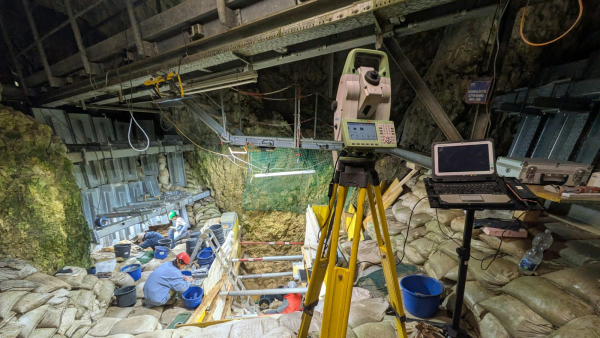

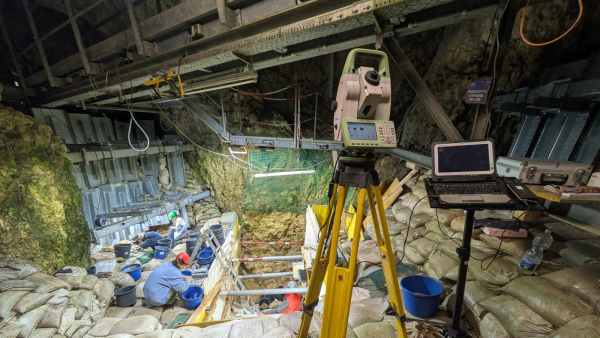

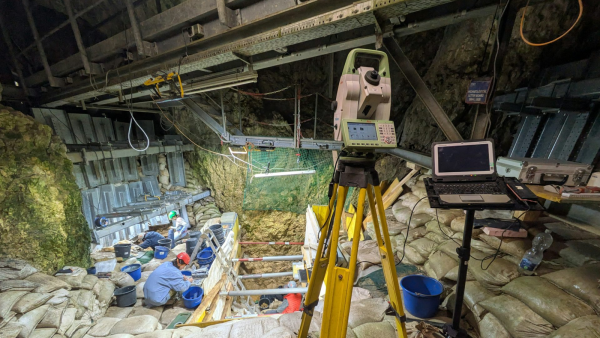

The investigation, revealed this Monday (Feb. 12) within the pages of the journal Nature Microbiology, encompassed situating 36 human deceased bodies at three distinct locales during the seasons of spring, summer, autumn, and winter. The scientific team opted for sites that were geographically distanced from one another — situated in Tennessee, Texas, and Colorado — possessing either a moderate, damp climate or a relatively dry climate.

Samples of genetic material were procured from the outer layer of the deceased’s epidermis, in addition to the soil surrounding them, over the initial span of 21 days postmortem. This period is characterized by decomposition occurring at a heightened tempo and with notable shifts, as organic materials commence rapid breakdown.

You may like

-

1,300-year-old poop reveals pathogens plagued prehistoric people in Mexico’s ‘Cave of the Dead Children’

-

‘Biological time capsules’: How DNA from cave dirt is revealing clues about early humans and Neanderthals

-

‘They had not been seen ever before’: Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Through a comprehensive examination of all genetic material, the researchers made the discovery that cadavers exhibited an identical microbial composition, irrespective of location, weather, or timeframe. Prior investigations had pinpointed notable constituents of this arrangement, yet were restricted to experimental lab environments or single location studies.

“What we ultimately unearthed was a multitude of microorganisms that manifested within each collection of data. These formed the fundamental decaying elements present across various settings,” elucidated Zachary Burcham, the initial author of the investigation and a research assistant professor associated with the University of Tennessee, in dialogue with Live Science.

This constellation of around 20 microbes comprised a blend of bacterial and fungal forms that are commonly unobserved within human bodies — specifically, until the onset of decay. Across the span of this study, researchers discerned that these tiny organisms surfaced within the deceased bodies with consistency, akin to a timed device, at particular junctures during the 21-day decaying timeframe. This observation directed them to infer that bugs engaged within the putrefaction phase, such as the Calliphora blow flies, alongside carrion beetles, bore responsibility for transmitting such microorganisms, potentially transporting them from a former cadaverous host.

Burcham stated that, beyond detecting identical microbes recurring across remains, they additionally noted these microbes underwent variations in quantity over time, following a pulsating pattern. By documenting the undulating shifts within different microbial populations, consolidating data, and applying a machine-driven learning architecture, they concluded they could estimate the timeframe over which the body had been undergoing putrefaction within a definite locale.

“We supplied the framework with microbial quantities as they altered through time, the time of year, and the setting,” Burcham clarified. “Yet, with remarkable consistency, the framework invariably determined the precise microbial elements themselves to hold paramount significance. It essentially prioritizes the search for these leading organisms, from which it derives the majority of insights or forecasts.”

Examining the microbial makeup in its entirety, the research personnel did detect variances amid the diverse locales and times of the year. However, the microbes reacting dependably to decay always appeared uniform, despite external influences. These constitute the microbes that the machine-driven model centers upon, thus disregarding the balance.

You may like

-

1,300-year-old poop reveals pathogens plagued prehistoric people in Mexico’s ‘Cave of the Dead Children’

-

‘Biological time capsules’: How DNA from cave dirt is revealing clues about early humans and Neanderthals

-

‘They had not been seen ever before’: Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Given that their constructed machine-driven framework offers the ability to estimate a person’s passing, alternatively termed the postmortem timeframe (PMI), the researchers surmise their discoveries could prove beneficial amid forensic inquiries across numerous locations and climates. The outcomes amassed up to the present moment have displayed elevated accuracy, with a possible variance of three days on either extreme.

The principal constituents within the recently identified network of microbial decomposers have previously demonstrated linkages to the remains of pigs, cattle, and rodents, implying their potential universality beyond humans.

Frederike Quaak, a microbiologist with the Netherlands Forensic Institute (NFI) maintaining no involvement within this investigation, articulated to Live Science that these findings might constitute a valuable inclusion within the resources employed for the approximation of PMI. Nevertheless, she emphasized further scrutiny warrants undertaking before these methods transition to real-world deployments.

RELATED STORIES

—70,000 never-before-seen viruses found in the human gut

—Scientists unveil ‘atlas’ of the gut microbiome

—Mysterious virus-like ‘Obelisks’ found in the human gut and mouth

“Actual case studies will invariably diverge significantly from their controlled investigations,” voiced Quaak regarding the recent publication. “Whereas they situate remains atop the ground, cases frequently entail submerged or interred remains ensconced within textiles or sealed receptacles, thereby diminishing accessibility to insect fauna. Such situations yield notably divergent trajectories of bodily degradation.”

Burcham verified ongoing endeavors to scrutinize the disintegration processes of organisms confined within sealed settings, in addition to interred remains, targeting the recognition of potential parallels surfacing thereof.

“Our efforts are directed at enhancing fundamental knowledge, with aspirations of prospective practical application in judicial procedures,” Burcham noted.

Do you ever ponder the varying ease with which individuals develop muscularity or the emergence of freckles upon sun exposure? Direct inquiries pertinent to the functionalities of the human frame to [email protected] bearing the heading “Health Desk Q,” to potentially witness your concern addressed on our digital platform!

Christoph SchwaigerSocial Links NavigationLive Science Contributor

Christoph Schwaiger functions as a self-employed journalist, centering principally on health, technological innovations, and ongoing happenings. His narratives have featured within Live Science, New Scientist, BioSpace, and the Global Investigative Journalism Network, amongst other publications. Christoph has participated in programs on LBC and Times Radio. Moreover, he formerly presided as a National President within Junior Chamber International (JCI), an international body fostering leadership, and completed his postgraduate studies at the University of Groningen in the Netherlands, securing an MA in journalism with honors.

Read more

1,300-year-old poop reveals pathogens plagued prehistoric people in Mexico’s ‘Cave of the Dead Children’

‘Biological time capsules’: How DNA from cave dirt is revealing clues about early humans and Neanderthals

‘They had not been seen ever before’: Romans made liquid gypsum paste and smeared it over the dead before burial, leaving fingerprints behind, new research finds

Scientists ‘reawaken’ ancient microbes from permafrost — and discover they start churning out CO2 soon after

Mysterious chunks of DNA called ‘inocles’ could be hiding in your mouth

Arctic ‘methane bomb’ may not explode as permafrost thaws, new study suggests

Latest in Death

What’s the longest someone has been clinically dead — but then come back to life?