“`html

Researchers employed brain imaging to comprehend how cells are arranged to react to both known and unknown locations.(Image credit: Andrew Brookes/Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Scientists have pinpointed a “switch” within the human brain that increases activity as we survey a fresh locale — a discovery that might clarify why disorientation frequently presents as an initial symptom in dementias, like Alzheimer’s.

Envision yourself on a typical walk towards your residence, then inadvertently making a detour. Swiftly, your brain sends out signals alerting you to your lost state.

You may like

-

Fresh research clarifies why the perception of time accelerates as we age

-

Study elucidates the reasons behind brain ‘blackouts’ during periods of exhaustion

-

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: Scientists learned how to manipulate memories in rodents

“When relocating to a new metropolis or journeying afar, assimilation isn’t instantaneous,” remarked Deniz Vatansever, a Fudan University neuroscientist in China and study co-author, to Live Science. “Environmental exploration is essential for familiarization.” Vatansever and colleagues sought to emulate this occurrence within VR.

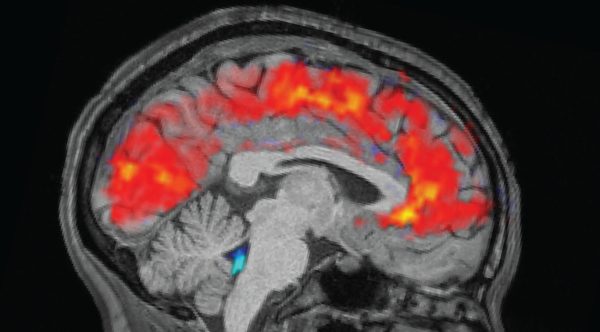

Fifty-six healthy participants, aged 20 to 37, were engaged and tasked with traversing a simulated realm within a scanner. Participants were instructed to navigate the virtual setting — a grassland encircled by peaks — whilst searching for six “objects” concealed throughout. Vatansever’s group used functional MRI, a method measuring cerebral blood flow, to track brain activity as the volunteers navigated across familiar and novel areas of this domain.

The research centered on the hippocampus, a cerebral region paramount for both memory and navigation. The hippocampus, resembling a seahorse, is abundant in place cells, which activate for particular locations. Prior studies indicate that one hippocampal end contains cells that trigger during consideration of general location, for instance, landmark placement in an adjacent urban center. Conversely, cells at the opposite end activate when contemplating specific sites, such as cereal box placement in one’s kitchen.

Positioned between the “beginning” and “end” of the hippocampus resides a gradient of activity uniting these broad and refined site depictions. Nevertheless, the cellular layout responding to a location’s novelty or acquaintance remained unexamined until now.

Vatansever’s cohort discovered that the head of the hippocampus held cells activating during participant explorations of prior locations. In contrast, cells at the tail were activated in new locales. Furthermore, the entire region exhibited a gradient pattern, transitioning from familiar to unfamiliar.

“The transition from recognizing something to experiencing something new is evident from end to end,” Vatansever stated.

Prior research yielded conflicting information regarding hippocampal regions responding to environmental novelty or familiarity, according to Zita Patai, a cognitive neuroscientist from University College London, unconnected with the study. “Their findings suggest that the discrepancy might stem from the gradient’s existence,” she informed Live Science.

You may like

-

Fresh research clarifies why the perception of time accelerates as we age

-

Study elucidates the reasons behind brain ‘blackouts’ during periods of exhaustion

-

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: Scientists learned how to manipulate memories in rodents

Different cerebral areas also showed varied responses to familiar and novel locations. The brain’s cortex — its advanced cognitive center — exhibited a cone-shaped gradient. “Centered within, segments indicate a ‘preference’ for acquaintance. As you move outward, there’s a heightened inclination to activate in response to novelty,” Vatansever clarified.

The team investigated whether navigating familiar and unknown regions activated wider brain networks, or groups of cells dispersed throughout the brain that frequently activate in unison. Recognizable regions activated networks formerly associated with motor skills and memory, whereas novel regions activated networks connected to focus and awareness.

Vatansever suggested that this separation might facilitate brain adaptation to unfamiliar contexts by centering on and assimilating relevant details. He proposed that memory and motor skills then merge to enable navigation of familiar zones.

These outcomes may shed light on some initial dementia indications, Vatansever posited. Coincidentally, cells within cortical and hippocampal gradients represent among the initial cerebral regions impacted by Alzheimer’s ailment. During the condition’s initial phases, the hippocampus’s frontal and rear zones are equally susceptible.

Louis Renoult, a cognitive neuroscientist at the University of East Anglia who did not participate in the research, commented on the paper’s illustration of navigation and memory’s solid correlation.

RELATED STORIES

—Most intricate human brain map yet details 3,300 cell variations

—Incredibly detailed mapping of brain cells responsible for wakefulness may enhance our comprehension of consciousness

—The brain may transition between related notions akin to navigating distinct locales

Renoult explained to Live Science that areas aiding navigation are also crucial to episodic memory, involving unique events in our lives, rather than factual knowledge. Moreover, episodic memory tends to be particularly frail during Alzheimer’s early stages.

A deeper insight into how navigation is encoded cerebrally could reveal measurable indicators of dementia’s initial phases, wherein navigational aptitude wanes.

Patai stated, “If an aim is to bolster individual independence, enabling them to explore novel locales and grasp new concepts is essential. In this context, the link between spatial novelty and memory holds significant intrigue.”

RJ MackenzieLive Science Contributor

RJ Mackenzie is a science and health reporter, celebrated for his work and nominated for awards. He possesses neuroscience degrees from both the University of Edinburgh and the University of Cambridge. He embraced writing, believing it the optimal route to contribute to science from the desk, rather than within the laboratory. His reporting spans a multitude of subjects, from brain-interface technology to materials science capable of shape-shifting, the proliferation of predatory conferencing, and the significance of programs for newborn screening. Formerly, he served as a staff writer for Technology Networks.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

New study reveals why time seems to move faster the older we get

Study reveals why the brain ‘zones out’ when you’re exhausted

‘As if a shudder ran from its brain to its body’: The neuroscientists that learned to control memories in rodents

The evolution of life on Earth ‘almost predictably’ led to human intelligence, neuroscientist says

How do our brains wake up?

‘Intelligence comes at a price, and for many species, the benefits just aren’t worth it’: A neuroscientist’s take on how human intellect evolved

Latest in Neuroscience

‘Mitochondrial transfer’ into nerves could relieve chronic pain, early study hints