“`html

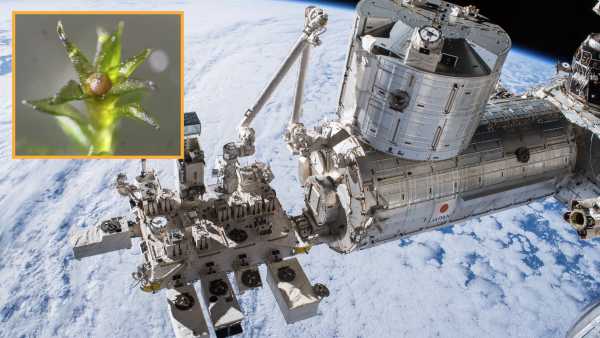

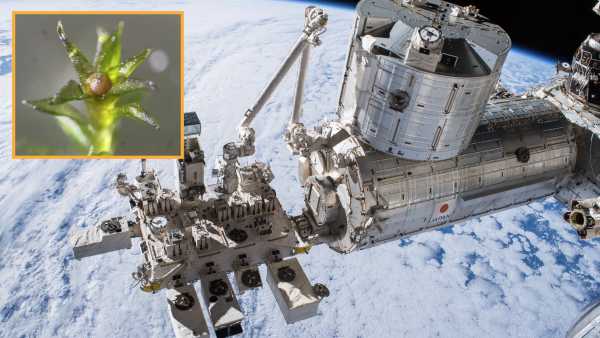

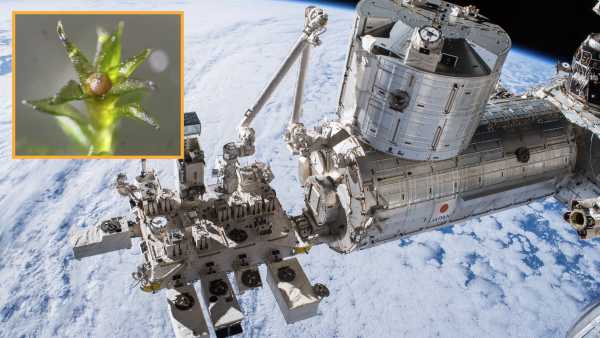

Researchers transported bacteria and bacteriophages, i.e., viruses which infect bacteria, to the ISS to examine their development.(Image credit: International space station (dima_zel/Getty Images); E.coli (Shutterstock))ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Microbes and their infecting viruses, known as phages, are entrenched in a perpetual evolutionary competition. This evolution, however, proceeds along a divergent route when the competition occurs in a condition of microgravity, according to a study undertaken on the International Space Station (ISS).

While microbes and phages clash, bacteria advance enhanced protections for existence while phages create updated mechanisms to infiltrate these safeguards. The recent investigation, appearing on January 13th in the journal PLOS Biology, gives specifics of how this combat progresses in space and reveals understandings that might aid us in formulating superior medications for bacteria on Earth that exhibit antibiotic resistance.

You may like

-

‘Stop and re-check everything’: Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA’s cleanrooms

-

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

-

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

The assessment of the space-station specimens demonstrated that microgravity inherently shifted the velocity and characteristic of phage contagion.

Although the phages remained proficient in infecting and eradicating the bacteria within the space setting, the duration of the procedure exceeded that witnessed among the Earth-based specimens. A prior piece of research by the same group of scientists put forward the theory that contagion cycles in microgravity might be slower considering that fluids do not combine as effectively in microgravity compared to Earth’s gravity.

“This current investigation gives support to our hypothesis and anticipations,” stated Srivatsan Raman, the primary writer of the study and an associate professor belonging to the Department of Biochemistry at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

On Earth, the liquids within which microbes and viruses are located are consistently agitated by gravity – warm water ascends, cold water descends, and heavier particulates settle downward. Such action retains everything dynamically moving and colliding.

Within the realm of space, such agitation ceases; every element merely levitates. Therefore, because the microbes and phages did not encounter each other as frequently, phages needed to adjust to a notably reduced tempo of existence, thereby refining their efficiency in latching onto microbes as they drifted by.

Authorities posit that comprehending this unique modality of phage development could guide them toward devising fresh phage treatments. These up-and-coming remedies for contagions deploy phages to eliminate microbes or increase the vulnerability of germs to conventional antibiotics.

“Should we unravel what genetic-level actions phages take to attune themselves to a microgravity milieu, we can transpose this acumen to experimentations concerning resistant bacteria,” commented Nicol Caplin, formerly working as an astrobiologist with the European Space Agency but unconnected with the study, in an electronic message to Live Science. “Additionally, this may represent a positive advancement in our endeavor to optimize antibiotics here on Earth.”

You may like

-

‘Stop and re-check everything’: Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA’s cleanrooms

-

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

-

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

Complete genome sequencing exposed the fact that the bacteria and phages housed at the ISS gained unique hereditary mutations not apparent within ground-based samples. The viruses within space garnered certain mutations that augmented their capability to infect microorganisms in concert with their aptitude at connecting with bacterial receptors. Concurrently, the E. coli exhibited mutations that served to insulate against the phages’ assaults — altering their receptors, by way of illustration — therefore elevating their chances of surviving within microgravity.

Subsequently, the scientists leveraged a technique referred to as deep mutational examination to scrutinize variations in the viruses’ proteins responsible for receptor binding. They ascertained that the adjustments prompted by the singular cosmic environment may bear pragmatic utilities back home.

When the phages had been conveyed back to Terra Firma and analyzed, the alterations within the receptor-binding protein resulting from the space setting displayed enhanced effectiveness versus E. coli lineages, which are frequently the root cause of urinary tract contagions. These lineages typically demonstrate resilience against the T7 phages.

“This eventuated as a serendipitous discovery,” remarked Raman. “We had not anticipated the [mutant] phages recognized on the ISS to eradicate pathogens upon Earth.”

RELATED STORIES

—Antibiotic discovered covertly in undeniable sight has potentials in addressing menacing contagions, initial research demonstrates

—How rapidly can resistance to antibiotics evolve?

—Antibiotic resistance renders erstwhile lifesaving medications futile. Might we be capable of reversing this?

“These outcomes underscore how space can enable us to augment the performance of phage treatments,” affirmed Charlie Mo, an assistant professor in the Department of Bacteriology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who lacked participation within the research.

“Nevertheless,” Mo continued, “we need to take into account the expense incurred in transporting phages into space or replicating microgravity conditions here on Earth to attain identical outcomes.”

Along with aiding in combatting contagions for patients bound to Earth, the investigation could potentially generate more efficacious phage treatments for usage in microgravity, according to Mo. “This holds potential significance for maintaining the health of astronauts amid extended space voyages — for example, journeys encompassing the moon, Mars, or drawn-out sojourns at the ISS.”

Manuela CallariLive Science Contributor

Manuela Callari is a freelance science journalist focusing on human and planetary well-being. Her work has been featured in MIT Technology Reviews, The Guardian, Medscape, and various other outlets.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

‘Stop and re-check everything’: Scientists discover 26 new bacterial species in NASA’s cleanrooms

Scientists put moss on the outside of the International Space Station for 9 months — then kept it growing back on Earth

This is SPARDA: A self-destruct, self-defense system in bacteria that could be a new biotech tool

Metal compounds identified as potential new antibiotics, thanks to robots doing ‘click chemistry’

That was the week in science: Vaccine skeptics get hep B win | Comet 3I/ATLAS surprises | ‘Cold Supermoon’ pictures

That was the week in science: Second earthquake hits Japan | Geminids to peak | NASA loses contact with Mars probe

Latest in Viruses, Infections & Disease

Why is flu season so bad this year?