Over the course of the COVID-19 crisis, public health officials endeavored to disseminate vaccinations fairly worldwide. They achieved substantial progress, though Dr. Seth Berkley believes even more can be accomplished in the future.(Image credit: Peter Dazeley via Getty Images)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this articleJoin the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Within a few weeks of the initial reports of a “strange ailment resembling pneumonia” emerging from Wuhan, China, public health leaders started gathering to analyze the danger and reinforce infrastructure to lessen any potential impending damage. This undertaking began developing many months prior to the formal declaration of COVID-19 as a worldwide pandemic.

Dr. Seth Berkley — a well-known epidemiologist specializing in infectious diseases and past CEO of Gavi, a worldwide institution focused on enhancing children’s entry to immunizations — was a leading individual involved in the endeavor to guarantee the distribution of potential COVID-19 vaccines to the world’s neediest countries. Berkley’s upcoming book, “Fair Doses: An Insider’s Story of the Pandemic and the Global Fight for Vaccine Equity” (University of California Press, 2025), recounts the efforts undertaken during the pandemic and considers both the successes and failures.

Live Science engaged in a discussion with Berkley regarding his book and the knowledge we must carry forward to prepare for the globe’s forthcoming major epidemic — an event which, Berkley asserts, is guaranteed to happen at some point.

You may like

-

Future pandemics are a ‘certainty’ — and we must be better prepared to distribute vaccines equitably

-

One molecule could usher revolutionary medicines for cancer, diabetes and genetic disease — but the US is turning its back on it

-

From gene therapy breakthroughs to preventable disease outbreaks: The health trends that will shape 2026

Nicoletta Lanese: What inspired you to author this book?

Dr. Seth Berkley: The core purpose of the book was to encapsulate the [pandemic] experience, taking place after COVID and COVAX. COVAX [COVID-19 Vaccines Global Access] represented the initiative that we launched when we recognized the increasing severity of the infection. While engaged with it, we encountered all kinds of obstacles, yet we did accomplish the most rapid and extensive vaccine rollout in history. We achieved primary dose coverage for 57% of the developing world’s population, specifically the poorest 92 countries, in contrast to a global rate of 67% — this falls short of ideal fairness, but is a step beyond any previous effort.

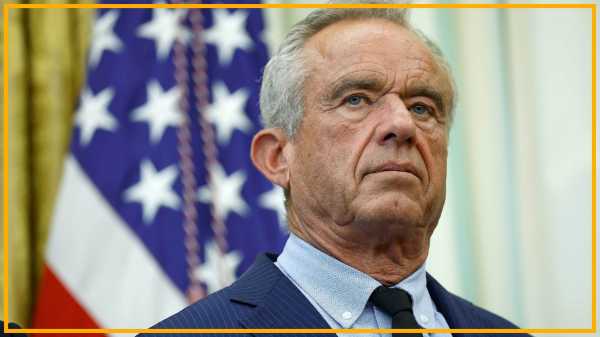

Dr. Seth Berkley.

My concern was primarily [that] people would fail to recognize the lessons learned, both beneficial and detrimental. The book aims to articulate the requirements to arrive at this place, pinpointing both the effective and ineffective players.

However, since composing the book, the global landscape has radically transformed. Although I had the option to rewrite the entire book from scratch, I chose not to. Yet, I seized the opportunity to express within the preface, and again in the book’s conclusion, the magnitude of these changes, especially considering the pervasive anti-vaccine sentiments now evident within the U.S. government. This is highlighted by figures such as the secretary of health and human services [HHS], Robert Kennedy Jr., who has a long history of vaccine skepticism and promoting conspiracy theories.

This situation is clearly alarming in terms of its potential impact on Americans. It is also important for Americans to comprehend the ripple effects of vaccine initiatives conducted internationally, because domestic and foreign sources contribute to the diseases we encounter.

NL: On that matter, we have seen a decrease in backing from the U.S. for programs intended to support equitable vaccine distribution globally. What consequences might this produce?

SB: Let’s consider the past 50 years as a timeframe for ease of understanding; fewer than 5% of individuals globally received a single vaccine dose. This includes not all suggested doses, but even a single one. We’ve transitioned from this state to a point where vaccines are now the most broadly dispensed health intervention worldwide. In tandem with this, deaths from preventable diseases due to vaccines have plummeted by 70%, and child mortality under five years has dropped by more than 50%, directly attributable to endeavors of this kind.

You may like

-

One molecule could usher revolutionary medicines for cancer, diabetes and genetic disease — but the US is turning its back on it

-

From gene therapy breakthroughs to preventable disease outbreaks: The health trends that will shape 2026

-

The US is on track to lose its measles elimination status in months. RFK needs to go.

Consequently, this is fundamentally significant. Furthermore, we have achieved control over numerous infectious diseases: the elimination of smallpox, near eradication of wild polio, effective management of measles in a significant number of countries, among others. These constitute our achievements. However, the current sentiment suggests retracting from these efforts at a time when these infectious ailments continue posing a threat — and, as demonstrated recently in the U.S., we have experienced considerable measles outbreaks.

The U.S. was recognized with a status affirming the removal of indigenous measles infections, implying that any new contaminations originated externally. Presently, the U.S. risks losing this status. This highlights the significance of a global outlook, as an increase in measles outbreaks in other nations, alongside the ebb and flow of human mobility, is projected to result in cases within the United States given declining vaccination figures. These rates are indeed decreasing.

We are in a situation where professionals are being discredited, and individuals lacking expertise or holding biased perspectives on vaccines are being assigned to positions of authority. Despite claims of aiming to increase trust, I find it difficult to perceive any trust enhancement in these actions. The U.S. is presently fragmented; as evidenced by the recent trend of states independently issuing recommendations. Professional organizations are also introducing their own guidance, leading to a lack of unified direction. In conclusion, I believe that this does not promote confidence.

NL: Do you perceive the recent U.S. shifts as an escalation of an established issue, or as the emergence of something entirely new?

SB: It is a fusion of both aspects. Hesitation towards vaccines is not a recent phenomenon, tracing back to the genesis of the first vaccine during the 1700s for smallpox shortly after its efficacy was confirmed. Early depictions, in response to the vaccine’s cow-derived origin, showcased people sprouting cow horns from their heads and other such imagery. It’s not a novel concern.

The novelty lies in the intense politicization — the concept that a particular political party holds and acts upon these beliefs disproportionately, resulting in variations in vaccine coverage across different parties. And finally, [there’s] the reality that government leaders are endorsing these conspiracy theories and disparaging establishments housing scientific experts and mechanisms designed to harness the most reliable scientific knowledge.

During COVID, we witnessed the spread of misinformation by Russian and Chinese bots, which spread rapidly. Furthermore, and unprecedentedly to my awareness, the U.S. government, specifically the Defense Department, engaged in spreading misinformation to undermine the Chinese vaccine. This form of warfare has devastating repercussions. … This denotes a completely elevated degree of anti-vaccine involvement compared to any seen previously.

Essentially, all parties should prioritize preventive healthcare spending over treatment investments, but this strategy is inconsistent with human inclination.

Dr. Seth Berkley, Brown University

NL: It is often argued that the efficacy of vaccines has diminished the perceived threat of vaccine-preventable ailments. Do you see this as a legitimate point?

SB: Observing this new era of misinformation — as stated before, misinformation about vaccines has been constant. However, if one resides in a nation with extremely high vaccination rates, thereby leading to the virtual elimination of illnesses, it becomes easy for a parent to rationalize, “I am not inclined for my child to be injected with a substance. … I am uninformed about these diseases. I’ve never experienced them. How dangerous could they be?” That’s one perspective.

Alternatively, inhabitants of developing nations where these ailments are actively circulating witness the complications experienced by children. There is an awareness of individuals paralyzed by polio, or those rendered blind or deaf as a consequence of rubella, often referred to as German measles. In this context, the benefit-to-harm perception is seen differently across these populations. It falls within the realm of science to evaluate the benefit-to-cost effectiveness of these products?

The lasting challenge is the absence of immediate visibility of these diseases which consequently obscures insight into the potentially severe repercussions. Consider the rare occurrence of subacute sclerosing panencephalitis due to measles which is a devastating development where the child’s brain undergoes irreversible dissolution, leaving no available intervention.

The complex balance is preventing persistent fear while ensuring that parents remain informed. Ensuring that children remain safe also comes with the crucial task of educating people about the possible, yet infrequent effects. Finding this balance is the ultimate goal, and education is the way to go.

NL: Another key aspect of the book is a strategy for achieving equality in global vaccination. What, in your opinion, are the greatest challenges for achieving this goal?

SB: The first part is what we’ve been talking about, understanding how valuable vaccinations are, and that is huge for everyone around the world. And remembering this stuff as diseases get rarer is also super important.

The next important thing is having easy access to vaccines. Gavi was good at getting many countries together so they could purchase vaccines in bulk, which dropped the price super low, about 98% less than in the United States. This made the vaccines much more affordable. They’re helpful even if they cost more, but it’s better when they don’t cost as much. Making sure we have enough vaccines and we’re making enough of them should be a top priority.

Then, we need good delivery systems, which can be tough. As I said at the beginning, vaccines are the health thing we give out the most. About 90% of families worldwide can get routine vaccines. … If we can reach that last 10%, we can not only give them vaccines but also offer other healthcare services. It also means there’s an early warning system so we always have health workers ready in case there are new diseases that pop up or new outbreaks that need to be taken care of.

Finally, it’s important to keep a close watch on what’s going on worldwide so we know if there are new diseases. Because of evolution, we know for sure there will be new diseases and big outbreaks, and that early alert system is super important for everyone everywhere. Putting money into stopping these diseases before they start is smart for everybody, and we need to make sure it’s a top thing we focus on.

NL: To reiterate, epidemics and pandemics are largely unavoidable. If that’s the case, how should we prepare?

SB: Based on evolution, epidemics are a sure thing. That being said, first thing’s first: we prepare for diseases we already know about, like flu, COVID, and hemorrhagic fevers. We’ve already got ways to deal with these. What we have to do is make sure the world is ready. That means having lab networks, stockpiling vaccines, and making sure we can make a lot of them when we need to.

Sadly, a lot of this stuff is getting taken apart right now. The U.S. is laying off people in important health organizations. We’re pulling out of the World Health Organization. Also, we’re changing the help we give to developing countries and we’re stopping scientists from getting training. This is all breaking down the systems we use to get ready for the diseases we know are coming, and that’s a real problem.

And as far as what we don’t know is out there, we also want to have the science ready to go. We should talk about pulling out of mRNA vaccines. [The HHS stopped giving money for research on mRNA vaccines.] It’s possible mRNA vaccines aren’t the best way to go for some diseases. However, they’re the fastest to make because you can whip them up fast from the genome. Then, you can basically “print” the vaccine and make a ton of it fast.

If there’s a super bad pandemic that has a high death rate, mRNA is the way to go to deal with it. For us to decide to stop working on mRNA — improving it, making it better — and instead stopping research seems super short-sighted to me.

NL: So, talking about mRNA, would you say that how fast you can make the vaccine is most important for pandemics? Or does mRNA do other stuff that’s useful?

SB: What’s absolutely the best thing about it is speed. And remember, COVID had a death rate of 1.5%, 2%. Some of the other diseases we know about that could spread have death rates of 20%, 30%, 40%, 50%. If you had something like that — if it’s something that spreads like the flu and kills a lot of people — every second you save counts.

So, mRNA is fastest. … Once you have mRNA vaccines, you could move to other vaccines that last longer, work better, and things like that [for whatever the disease is]. But it takes longer to make those, so you could swap them out one by one as they’re ready.

One of the problems during COVID was that over 200 different vaccines were created, but mRNA was so quick that the others didn’t have a chance to get out there. One example is the Novavax vaccine, which is protein-based. Even though it was good at protecting people and safe, and maybe lasted longer, it just never got really popular worldwide.

What’s hard is figuring out in these situations which products are actually the best. Drug companies won’t do tests themselves, because it’s not good for business to test your product against someone else’s. International organizations and governments are the ones that need to do that.

RELATED STORIES

—Future pandemics are a ‘certainty’ — and we must be better prepared to distribute vaccines equitably, says Dr. Seth Berkley

—’The Big One’ could be even worse than COVID-19. Here’s what epidemiologist Michael Osterholm says we can learn from past pandemics.

—Nobel Prize in medicine goes to scientists who paved the way for COVID-19 mRNA vaccines

NL: Is there anything else readers can expect from “Fair Doses”?

SB: The book also has lots of interesting stories of who did a good job and who didn’t during the pandemic. I’m talking about political leaders, pharmaceutical companies, and organizations. It gives you a more in-depth look at what things were really like back then.

We came together with our partners to try to change the norm in a pandemic: rich countries buying all the vaccines and no one else getting them. That was our goal from the start. In the book, I tell the story of how we made this plan, how we got $12.5 billion to buy vaccines, and how we got over 2 billion vaccines to 146 countries.

One of the big questions is, how can we do this better? What can we take away from it? And we try to figure that out in the book.

Editor’s note: The interview has been modified slightly to make it shorter and easier to read.

Disclaimer

This article is solely for informational purposes and does not constitute medical advice.

$29.95 at Amazon

Fair Doses: An Insider’s Story of the Pandemic and the Global Fight for Vaccine Equity

“Fair Doses” delves into the realm of vaccines, exploring their origins, significance, and global dissemination, highlighting that the pursuit of universal access remains a challenge. In this engrossing analysis, Dr. Seth Berkley, a globally esteemed epidemiologist of infectious diseases and a leader in public health, provides firsthand insights into the intricate aspects of creating and implementing vaccines for a spectrum of ailments, spanning from Ebola to AIDS to malaria and beyond.

TOPICSvaccines

Nicoletta LaneseSocial Links NavigationChannel Editor, Health

Nicoletta Lanese is the health channel editor at Live Science and used to be a news editor and writer there. She got a certificate in science communication from UC Santa Cruz and went to the University of Florida for neuroscience and dance. She’s been published in The Scientist, Science News, the Mercury News, Mongabay, and Stanford Medicine Magazine, among others. She lives in NYC and still dances a lot, performing in local shows.

Read more

One molecule could usher revolutionary medicines for cancer, diabetes and genetic disease — but the US is turning its back on it