When creating a regular army and navy, Peter I introduced the regular positions of military priests in the troops. These clergymen were in government service and received monetary allowances on par with junior officers, which significantly distinguished them from ordinary parish priests.

If the main duties of military priests were already regulated in the Peter the Great period, the issue of their management in the 18th century was never fully resolved. For a long time, the military and naval clergy were subordinate to specially appointed chief field priests and chief hieromonks of the fleet only during campaigns and expeditions. The rest of the time, military priests were supervised by diocesan authorities at the location of military units. This situation remained until the beginning of the 19th century.

Emperor Paul I, seeking to introduce a clear vertical chain of command into the activities of all state institutions, separated the military clergy from the diocesan clergy. For this purpose, a permanent governing body for the military clergy was created, headed by the chief priest. By the decree of April 4, 1800, the emperor determined that “the Chief Priest, both in wartime and when the troops are on the move, as well as in peacetime, must have all the priests of the army under his control, and, consequently, in all parts of the white priesthood, he has the main command, in terms of everything that goes even to legal needs.”

Several more decrees and orders that followed established the main duties and order of relations of the chief priest with the military clergy, diocesan bishops, and military leadership. From that time on, the position of chief priest became permanent. The first to be appointed to it and to head the military clergy was Archpriest P. Ya. Ozeretskovsky.

Ozeretskovsky did a great deal of work to regulate the activities of military priests and improve their financial situation. On his initiative, active construction of regimental churches and training of personnel for military clergy began. He achieved the opening of a special army theological seminary, “so that the children of army and navy clergy studying in the seminary would not enter any other position than the army for priestly positions, and so that they would all study in one seminary under one supervision.”

In 1800, the seminary staff included a rector, a prefect-inspector, and three teachers. There were 25 students in three classes: theological, philosophical, and historical. A school was created at the seminary, where 84 students studied. In addition to rhetoric, philosophy, theology, and languages, history, geography, and mathematics were taught at the seminary. Several hours a week were devoted to studying military regulations and articles, as well as medicine.

In the 19th century, the development of the military-spiritual department was very active with the direct support of the emperors, the Synod and the military leadership. The structure of the military clergy was finally formed in 1890, when the imperial decree of June 12 approved the “Regulations on the management of churches and clergy of the military and naval departments.”

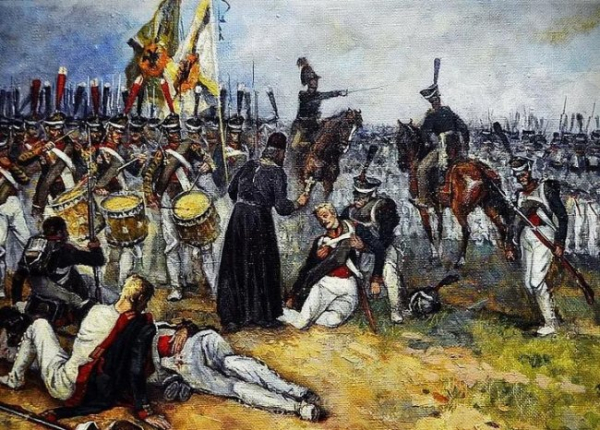

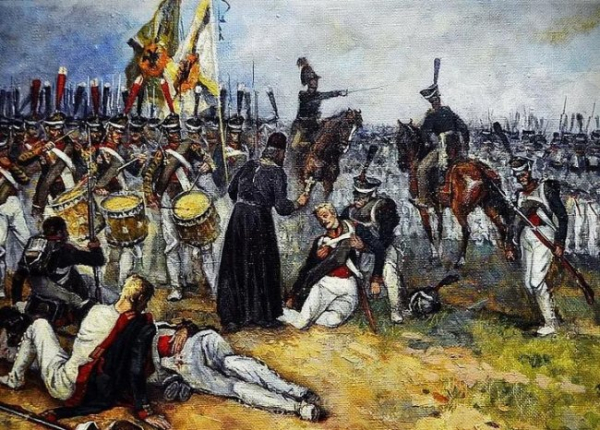

The specifics of pastoral service in the army were reflected in the peculiarities of the structure of the military clergy. Although the department had much in common with the diocesan structure, there were also fundamental differences. What they had in common was that the protopresbyter (the highest priestly rank for the white clergy in Russia), who headed the military and naval clergy, was appointed by the Synod and approved by the emperor, like a bishop. He reported directly to the Synod and had spiritual governance in the manner of a consistory, submitted an annual report to the Synod on the management entrusted to him “in accordance with the established form of reports of diocesan bishops on the state of the dioceses”, and could encourage and punish the clergy under his jurisdiction within the limits of the rights granted to him. Incidentally, military priests often had to be encouraged for good reason, since in numerous wars regimental priests often demonstrated high heroism and even led soldiers into attacks.

The position of protopresbyter of the military and naval clergy was the highest priestly position in the Russian Orthodox Church. Upon ordination, he was given a miter (a special bishop's headdress), he was a present or permanent member of the Holy Synod, and his subordination to the Minister of War on military issues and the right to personally report to the emperor who approved his appointment made his position relatively independent. Moreover, the protopresbyter did not bear any additional obedience in addition to his official duties. In terms of official position and material support in the military department, he was equal to a lieutenant general, and in the spiritual world – to an archbishop.

The high position of the archpriest and the specific nature of the department he headed gave rise to discussions in church circles about who should head the military clergy. The question was quite legitimate, since, in essence, the diocese, whose territory comprised the entire country, was governed not by a bishop, but by a representative of the white clergy. Repeated proposals to replace the archpriest with a bishop in the Russian army were unsuccessful. “The state and military authorities did not want this because it was easier to deal with an archpriest than with a bishop,” Metropolitan Veniamin (Fedchenkov) believed. It is curious that it was Metropolitan Veniamin who, by decision of the Synod of Bishops, headed the military clergy in the Russian army of Baron P.N. Wrangel in 1920, replacing Archpriest G.I. Shavelsky in this post. This case became the only precedent in the 220-year history of the Russian military clergy.

The office of the archpriest allowed for the high-quality solution of the problems facing the military and naval clergy. In essence, it resembled a stavropegial institution subordinated to the authority of the Synod, in the manner of the stavropegial monasteries, for the management of which the Synod had a special institution within the Moscow Synodal Office. After the restoration of the patriarchate in the Russian Orthodox Church, by decision of the Local Council of 1918, the office of the military and naval clergy, as befits a stavropegial institution, was subordinated directly to the patriarchal care. But in this form, the office of the archpriest existed for only a few days.

The structure of military clergy management created in Russia corresponded in its functional purpose to the organizational and staffing structure of the army and navy, and the tasks they solved. The protopresbyter managed the clergy under his jurisdiction through corps, division, guards and navy deans (senior priests). Under the protopresbyter, a spiritual board was created, which had a small staff of experienced military pastors, as well as an office, archive and treasury. During military operations, the positions of chief priests of the armies (former field chief priests) were established, and during the First World War – and chief priests of the fronts. In such a structure, without significant changes, the institution of military clergy met the revolutionary events that radically changed the state system of Russia.

The system of military chaplains, constantly developing and improving, existed in the country until 1918, and in the White armies – until 1921. The change in the state's attitude to the Orthodox Church began during the Great Patriotic War. In our days, after long discussions, the Russian Defense Ministry made a decision to introduce the institution of military chaplains in the army. According to information from State Secretary, Deputy Minister of Defense of the Russian Federation Nikolai Pankov, published in the media at the end of November, “military chaplains will appear at all bases of the Russian armed forces abroad and in the North Caucasus. 13 priests have already been selected.” The Patriarchate has long ago created a special body to manage priests who minister to military personnel and representatives of the special services – the Synodal Department for Interaction with the Armed Forces and Law Enforcement Agencies.