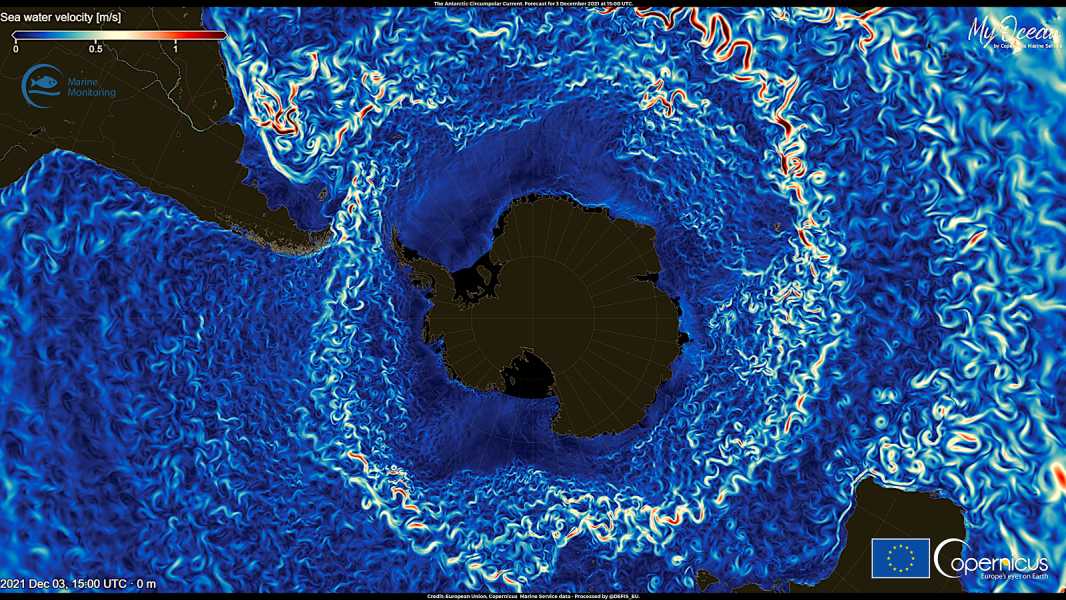

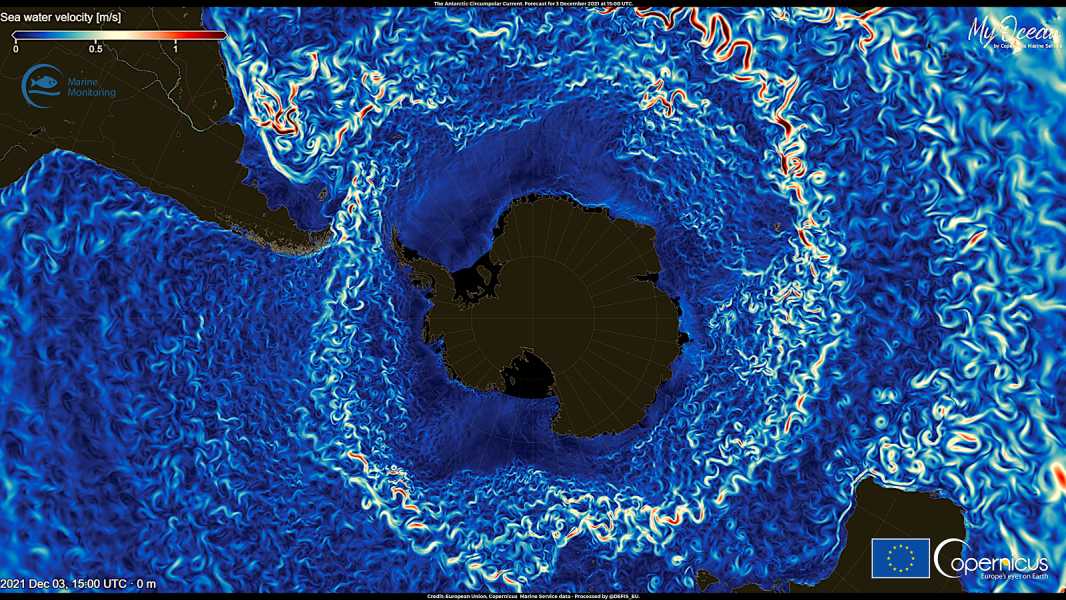

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current is the most powerful ocean current on the planet. (Photo credit: European Union, Copernicus Marine Environment Monitoring Service)

Melting ice in Antarctica is slowing the planet's most powerful ocean current, according to a new study.

An influx of cold meltwater could reduce the speed of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current by 20% by 2050, researchers reported March 3 in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The slowdown could impact ocean temperatures, sea levels and Antarctica's ecosystem, the team said.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current, which rotates clockwise around Antarctica, carries about a billion liters (264 million gallons) of water every second. It keeps warmer water away from the Antarctic ice sheet and connects the Atlantic, Pacific, Indian, and Southern Oceans, creating a pathway for heat exchange between these bodies of water.

Climate change has caused Antarctic ice to melt rapidly in recent years, increasing the influx of fresh, cold water into the Southern Ocean. To understand how this influx will affect the strength and circulation of the Antarctic Circumpolar Current, Bishahdatta Gayen, a fluid mechanics specialist at the University of Melbourne in Australia, and his team used Australia’s most powerful supercomputer and a climate simulator to model the interactions between the ocean and the ice sheet.

The researchers found that fresh, cold meltwater likely weakens the current. The meltwater dilutes the surrounding seawater and reduces convection between the surface and deep waters near the ice sheet. Over time, the deep Southern Ocean will warm because convection will bring less cold water from the surface. The meltwater will also move further north before sinking. These changes together affect the density profile of the world's oceans, causing the current to slow.

This slowdown could allow more warm water to reach the Antarctic ice sheet, exacerbating the melting that is already occurring. In addition to raising sea levels, this could add even more meltwater to the Southern Ocean and further weaken the Antarctic Circumpolar Current.

The Antarctic Circumpolar Current also serves as a barrier against invasive species, channeling non-native plants—and the animals that travel with them—away from the continent. If the current slows or weakens, this protective function could become less effective.

“It's like a carousel. It keeps going round and round, so it takes longer to get back to Antarctica,” Gayen said. “If it slows down, it could cause everything to migrate very quickly to the coast of Antarctica.”

It’s hard to predict when we’ll start feeling the effects — if we haven’t already. The Antarctic Circumpolar Current hasn’t been tracked for long because it’s so remote, Guyen told Live Science. To better distinguish warming-induced changes from baseline conditions, “we need long-term records,” he said.

The effects of the slowdown will be felt even in other oceans. “This is the heart of the ocean,” Gayen added. “If something stops there or something happens, it will affect every ocean circulation.”

Antarctica Quiz: Test Your Knowledge of Earth's Frozen Continent

Sourse: www.livescience.com