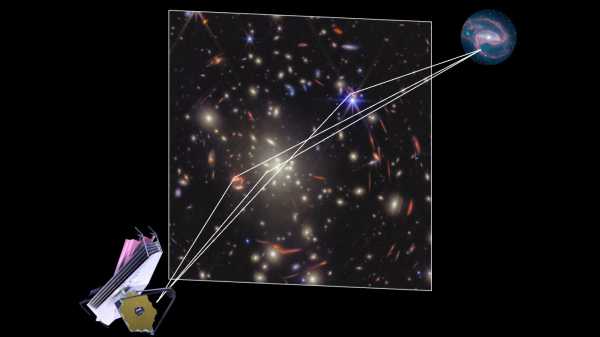

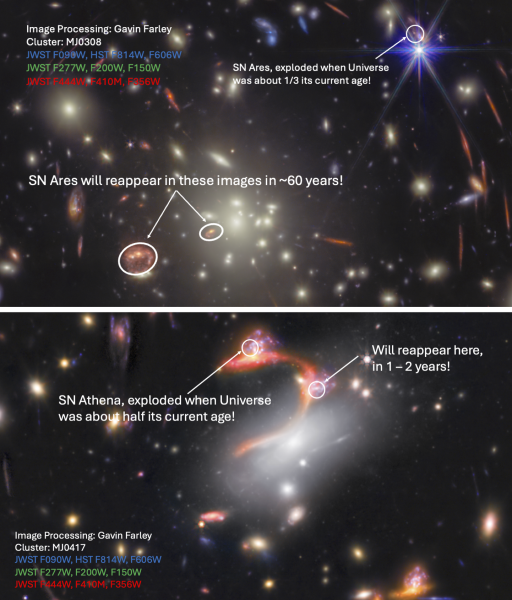

The immense MJ0308 galaxy grouping at the front generates a gravitational lensing occurrence, which results in several visuals of SN Ares to come into view. (Image credit: NASA/ESA/CSA/image processing: Gavin Farley)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Two notably scarce supernovas that broke out eons ago present a remarkable chance to clarify cosmology’s greatest enigma — At what rate is the cosmos growing?

But there’s a snag: Although astronomers have already scrutinized these exploding celestial objects, we will have to bide our time for approximately 60 years for their radiation to get to us again.

An effect termed gravitational lensing has divided the light from these extinguished stars into numerous images, each of which follows a different route via space-time to reach us. Consequently, investigators will ultimately be able to assess the gap between these spectral visuals to provide an extraordinary limitation on the expansion pace of the cosmos — an issue that has long bewildered researchers, as the cosmos seems to be expanding at differing paces depending on where they observe.

You may like

-

James Webb telescope might have detected the earliest supernova in the cosmos

-

James Webb telescope uncovers earliest Type II supernova in the recognized cosmos

-

First-ever ‘superkilonova’ binary star detonation mystifies astronomers

Cosmic magnifying glasses expose the invisible

These supernova observations are among the first outcomes from the Vast Exploration for Nascent, Unexplored Sources (VENUS) treasury initiative. The VENUS study employs the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) to observe 60 dense galaxy clusters, which function as cosmic lenses that divide and direct the radiation from tremendously distant, otherwise unseen sources such as supernovas.

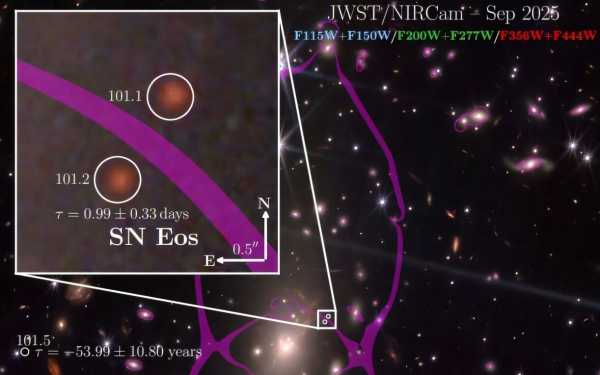

Combined data from the Hubble Space Telescope and the James Webb Space Telescope seize the gravitationally lensed supernovas SN Ares and SN Athena. The researchers can forecast when and where their images will manifest again down the road.

This cosmic occurrence, dubbed gravitational lensing, is a direct outcome of gravity’s impact on the framework of space-time and was initially put forward by Albert Einstein in his theory of relativity. It arises when a massive celestial object, like a galaxy cluster, curves the radiation from a more distant source that’s positioned behind it, thereby magnifying the object.

“Strong gravitational lensing transforms galaxy clusters into nature’s most potent telescopes,” Seiji Fujimoto, principal investigator of the VENUS initiative and an astrophysicist at the University of Toronto, stated in a declaration. “VENUS was designed to maximally find the rarest events in the distant Universe, and these lensed [supernovas] are exactly the kind of phenomena that only this approach can reveal.”

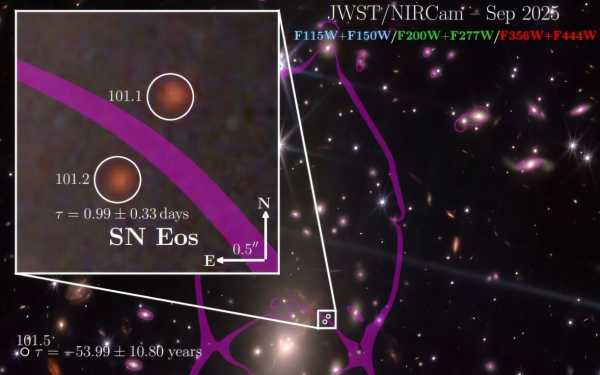

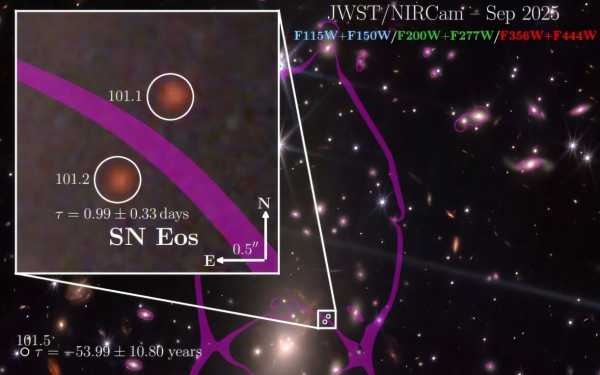

SN Ares is the first lensed supernova discovered via the VENUS initiative. The detonation took place virtually 10 billion years prior, when the cosmos was approximately one-third its current age. The distortion in space-time triggered by a foreground galaxy cluster, MJ0308, split the radiation from SN Ares into three images.

One image has already arrived at our telescopes. But the radiation from the other two images passes much nearer to the massive center of MJ0308, so it undergoes a much bigger retardation due to gravitational time dilation. Therefore, the other two visuals of SN Ares will appear in roughly 60 years — a groundbreaking delay.

“Such a long anticipated delay between images of a strongly lensed supernova has never been seen before and could be the chance for a predictive experiment that could put unbelievably precise constraints on cosmological evolution,” Larison stated in a declaration.

You may like

-

James Webb telescope might have spotted the earliest supernova in the cosmos

-

James Webb telescope uncovers earliest Type II supernova in the recognized cosmos

-

First-ever ‘superkilonova’ binary star detonation mystifies astronomers

In the meantime, a delayed image of SN Athena, which erupted as a supernova when the cosmos was around half its current age, is anticipated to appear in the coming one to two years. Although it won’t be as cosmologically precise as its mythological half sibling Ares, Athena will disclose how accurate our predictive capabilities have grown.

A sorely needed natural experiment

The predicted reappearance of these supernovas, contrasted with their actual arrival times down the road, will present precise constraints on the expansion pace of the cosmos, a value recognized as the Hubble constant.

Oddly, when cosmologists assess the Hubble constant, they acquire differing values based on the assessment technique — a disparity recognized as the Hubble tension. Calculations based on the cosmic microwave background — the most ancient radiation in the cosmos, emitted when the cosmos was just 380,000 years old — yield a universal expansion pace of 67 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

Yet calculations based on the Hubble Space Telescope’s observations of pulsating Cepheid stars, used as “standard candles” for their specific luminosity patterns, yield a value of 73 kilometers per second per megaparsec.

Within the observable sphere of the cosmos, the delayed images from SN Ares and SN Athena may assist in reconciling the Hubble tension.

“If we can measure the difference in when these images arrive, we recover a measurement of the physical scale of the lensing system which spans the Universe between the supernova and us here on Earth,” Larison told Live Science via email. “Any distance measurement we can make like this in the Universe tells us how the Universe has been evolving over cosmic time, as these distances directly depend on this evolution.”

Equally importantly, the lensed supernovas allow astronomers to make this measurement in a “single, self-consistent step,” Larison added.

The time delays from these supernovas also permit an independent assessment technique — unrelated to the cosmic microwave background or standard candles like Cepheid stars — at a time when such an assessment is “sorely needed” to test “possible unknown systematics” governing cosmological expansion.

From Big Bang to big mystery

Coincidentally, 60 years have elapsed since the initial formal suggestion to utilize lensed supernovas as a tool to explore the universe’s expansion. However, fewer than 10 such supernovas had been discovered before the VENUS initiative observations.

“Since VENUS started last July, we have discovered 8 new lensed supernovae over 43 observations, almost doubling the known sample in a remarkably fast time frame,” Larison told Live Science. “It seems that, although lensed supernovae are certainly rare, the real limitation has been in observing capabilities. It is really only with JWST that we are achieving the depth and wavelength coverage necessary to find these en masse, which is exactly what VENUS was designed to do.”

related stories

—James Webb telescope spots Milky Way’s long-lost ‘twin’ — and it is ‘fundamentally changing our view of the early universe’

—’I was astonished’: Ancient galaxy discovered by James Webb telescope contains the oldest oxygen scientists have ever seen

—’Totally unexpected’ galaxy discovered by James Webb telescope defies our understanding of the early universe

As a result, lensed supernovas may be the most thrilling prospects in long-baseline cosmology, the study of how the cosmos has altered throughout its 13.8 billion years of existence.

The solution is up in the air; there’s no assurance that the expansion of the cosmos will continue to accelerate, especially as dark energy may be diminishing. If it is, then the current expansion of the cosmos could at some point turn into a contraction, having profound repercussions on the eventual fate of the cosmos.

Ultimately, SN Ares and SN Athena may hint at the potential demise of the cosmos and whether it concludes with a bang or a whimper — will the cosmos fall in on itself in a Big Crunch, or expand endlessly into the thin, chilly darkness of a Big Freeze?

Ivan FarkasLive Science Contributor

Ivan is a long-time writer who loves learning about technology, history, culture, and just about every major “ology” from “anthro” to “zoo.” Ivan also dabbles in internet comedy, marketing materials, and industry insight articles. An exercise science major, when Ivan isn’t staring at a book or screen he’s probably out in nature or lifting progressively heftier things off the ground. Ivan was born in sunny Romania and now resides in even-sunnier California.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

James Webb telescope might have detected the earliest supernova in the cosmos

James Webb telescope uncovers earliest Type II supernova in the recognized cosmos

First-ever ‘superkilonova’ binary star detonation mystifies astronomers

Standard model of cosmology holds up in massive 6-year study of the universe

Strange, 7-hour explosion from deep space is unlike anything scientists have seen — Space photo of the week