MEMBER EXCLUSIVE

The James Webb Space Telescope (at the forefront) has radically altered the quest to discover alien worlds where life could potentially thrive. Might this instrument be the one to at last resolve a paramount inquiry of the universe?(Image credit: Photo collage designed by Marilyn Perkins. Images courtesy of NASA, ESA, CSA, Northrop Grumman; Nazarii Neshcherenskyi via Getty Images; NASA, ESA, CSA, K. McQuinn (STScI), J. DePasquale (STScI))ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 1Engage in the conversationFollow usAdd us as a go-to resource on GoogleNewsletterJoin our mailing list

Envision a world twice the expanse of Earth, swathed in an ocean that carries a scent akin to cooked greens.

Each day, a diminutive crimson sun radiates warmth upon this aquatic realm and the countless multitudes of voracious, plant-like organisms that call it home. Ascending to the surface in immense numbers, they coalesce into a vibrant, drifting landmass exceeding the area of Australia — discharging a sharp-smelling gas as they convert solar rays into sustenance.

The sulfur-rich gas billows outward from the extraterrestrial proliferation, saturating the atmosphere so intensely that a solitary telescope positioned 700 trillion miles (surpassing a quadrillion kilometers) distant can discern it — faintly, for mere hours each month, as the water-bound world transits before its small, ruddy star. During these brief intervals, the unusual algae of the pungent planet make their presence recognized on Earth.

You may like

-

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is rapidly moving away from us. Can we ‘intercept’ it before it leaves us forever?

-

Science history: James Webb Space Telescope launches — and promptly cracks our view of the universe — Dec. 25, 2021

-

Best space photos of 2025

This might seem like pure fantasy … but is it truly?

For the previous couple of years, this query has fueled animated discourse amongst researchers devoted to extraterrestrial exploration, especially in connection to the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST). The planet K2-18b, situated around 120 light-years from our own, has been carefully scrutinized through this sophisticated instrument. While the planet’s existence is validated, specifics about its environment and the possibilities for it to sustain life, are still debated.

Science Spotlight provides a more extensive exploration of developing scientific disciplines, offering our audience the insights essential for appreciating the progress. The articles underscore evolving trends, highlight how novel studies reshape long-held ideas, and explore shifts occurring in our perception of existence as breakthroughs arise in the realm of science.

A team of scientists employing JWST to analyze K2-18b over the course of several years assert the presence of dimethyl sulfide (DMS). The characteristic scent of this substance is reminiscent of cabbage, commonly identified as the “sea smell,” and, as far as we understand, is solely produced by active phytoplankton. Initial signals hinting at DMS within the atmosphere of K2-18b were documented by this team in 2023, which they have since reinforced through further studies.

However, external investigators harbor doubts concerning the purported discovery of DMS. They have voiced apprehensions that the team’s findings hinge on possibly suspect data interpretations and are not firmly substantiated to the degree needed to declare a fresh scientific breakthrough. It will require more study to give a definitive response.

Nevertheless, it is unquestionable that the potent infrared technology of JWST is supplying the most promising opportunity humanity has ever had to detect life beyond Earth.

The impact of JWST, as noted by Eddie Schwieterman, an assistant professor specializing in astrobiology at the University of California, Riverside, who explores the habitability of exoplanets using JWST, is that “we’re accumulating information in the space of just a few years that surpasses everything obtained in previous decades regarding the makeup of atmospheres beyond our solar neighborhood.”

Within the domain of alien life pursuit, it’s generally accepted that an atmosphere implies potential surface water, and where there’s freely flowing water, life could exist. JWST marks the first instance where the composition of alien atmospheres comes into sharp focus.

You may like

-

Interstellar comet 3I/ATLAS is rapidly moving away from us. Can we ‘intercept’ it before it leaves us forever?

-

Science history: James Webb Space Telescope launches — and promptly cracks our view of the universe — Dec. 25, 2021

-

Best space photos of 2025

Victoria Meadows, a professor of astronomy at the University of Washington and the director of the astrobiology program for graduate students, states that “we are truly at a watershed period in the quest for life because we now possess the technical ability to explore it.” She adds, “Prior to JWST, our ability to do this was severely limited.”

An artist’s illustration represents exoplanet K2-18b, presented as it might look given current scientific interpretations of it being primarily an ocean world. The diminutive red sun K2-18, hovering approximately 120 light-years from our planet, casts a faint light from the left. The Exhalations of Extraterrestrials

When it comes to spotting potential livable planets — those orbiting within their star’s “Goldilocks zone,” which ensures water remains in a liquid state — JWST stands alone.

JWST, in stark contrast to Hubble and similar optic instruments, lacks the ability to make direct observations of the ground on faraway planets. Also, it isn’t designed to pick up radio waves or other “technosignatures” potentially sent by superior beings. Alternatively, JWST zeroes in on more subtle signs of life. Its aim isn’t to offer crisp shots of suspected pathways or unusual transmissions but to identify subtle traces of chemicals floating invisibly above a planet.

Sebastian Zieba, a researcher engaged in postdoctoral studies at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, stated that “the initial step in identifying life consists of pinpointing an atmosphere, which is a pre-condition for liquid water to thrive on the planet’s surface.”

Compared to its antecedent — NASA’s Spitzer Space Telescope (operational between 2003 and 2020) — JWST is far “superior in all facets,” as per Zieba. It is capable of observing greater cosmic distances and can identify across a broader spectrum of infrared wavelengths, going beyond any prior telescope’s abilities. The capability to identify infrared emissions proves critical for tracing life, given that such wavelengths effectively encode details concerning chemical constituents that are absorbing or re-releasing sunlight across a planet’s atmosphere.

To facilitate the detection of an exoplanet’s atmospheric traces, JWST requires precise timing to intercept what’s termed as a transit — occurring when the planet moves ahead of its host sun, allowing the sun’s rays to penetrate through the planet’s aerial envelope from Earth’s vantage point. In the instance of K2-18b, this repeats every 33 days.

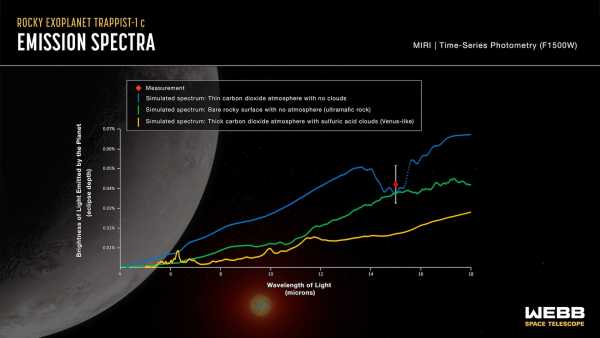

Three possible emission spectra are showcased for the terrestrial exoplanet TRAPPIST-1c, illustrating the variation in the planet’s visual brightness contingent on the light’s wavelengths. Alterations in wavelengths are a consequence of diverse molecules absorbing and radiating light, an occurrence scientists use to gauge the composition of planets and their overlying atmospheres. JWST’s analysis (indicated by a red diamond) is most aligned to a bare, craggy terrain planet void of any significant atmosphere (as depicted through the green trendline). Essentially, it’s not a promising place for extraterrestrial inhabitants.

Meadows explains that as “the planet shifts in front of the star, it essentially illuminates the gases present in its atmosphere.” She references this phenomenon metaphorically as “a subtle halo surrounding the planet.”

This “halo” harbors important details about the far-off locale. As sunlight traverses the planet’s atmosphere, molecules within either consume or reflect distinct wavelengths, modifying the observations JWST documents at those wavelengths. The compilation of various wavelengths form a distinct signature or a spectrum, indicating components found in the atmosphere. The spectrum further helps astronomers deduce the planetary dimensions, ground conditions, the layout, and potential life-supporting abilities.

By illustration, Meadows suggests that discovering significant methane with carbon dioxide levels in a planet’s spectrum suggests it could mirror Earth during the Archean eon (roughly 4 billion to 2.5 billion years prior), characterized by the presence of basic organisms breaking down CO2 while releasing a heavy methane flow.

Yet validating the scenario, trillions of miles away, has proved difficult.

Data Interpretation’s Challenges

Following a successful biosignature identification, it’s essential to rule out chances of geological elements, such as volcanic activities. Progressing ahead, scientists are bound to prove if their identification stands on statistical grounds — needing numerous recurring planetary assessments with validations through independent data interpretations.

René Doyon, a professor at the University of Montreal who takes the lead as the principal investigator with JWST’s Near Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) instrument, shares that “analyzing Webb’s data is notably intricate and researchers have been publishing results that often show inconsistencies, as they vary according to the data interpretation methods being adopted.”

The preliminary reports on K2-18b came into focus here. While a possible DMS identification was reported across two studies driven by the University of Cambridge-led experts, neutral parties have, so far, fallen short when trying to align it, looking at the same observations, yet implementing varied data modeling methods. Also, the DMS identification was found to have statistical significance reaching only the three-sigma mark, under the five-sigma requirement. (A three-sigma mark reflects approximately a 3/1000 fluke-level probability, as the five-sigma mark means a 1/3.5 million chance of being a fluke).

Nikku Madhusudhan, an astrophysics professor at Cambridge and the leading specialist behind the two DMS investigations, stated this offers negligible reason to dismiss K2-18b as a world with potential habitation “swarming with microbial life.”

Madhusudhan shares that “we have starting feelers regarding our findings, yet it is possible we could be wrong; therefore, remaining receptive to being incorrect and pursuing more data is important, for it is only by that means can we endorse the identifications.”

Schwieterman considers the DMS identification on K2-18b as “premature,” given the uncertainty in statistical grounds. All the same, he consents that DMS remains an encouraging biosignature that JWST should target across other likely habitable water worlds.

Schwieterman further notes that “the question centers on how widespread global biospheres remain in the cosmic neighborhood.” If intricate life prevails, including intelligent variations, then “the question largely lies in how frequent are the biospheres where the complicated life forms originate.”

Hitting a “Bull’s-Eye”

Irrespective of life manifesting around K2-18b, the far-off planet joins several destinations JWST keenly targets.

The Telescope’s investigation also involves routine suspects, which include the TRAPPIST-1 system — an extensively studied star system next to our cosmic backyard. Within that zone, the system hosts seven rocky planets, among which no less than three seem positioned under a habitability “Goldilocks” zone.

Thus far, it’s unconfirmed if JWST validates an atmosphere around any of the planets, in respect to potentially habitable planets TRAPPIST-1b, c or d. Regardless, a report presented in The Astrophysical Journal Letters on September 8 offered possible indications with regard to a likely nitrogen-based atmosphere enveloping TRAPPIST-1e, rendering it among the promising candidates suggestive of an Earth-like planet, outside our solar system.

In parallel, Doyon advocates for studying LHS 1140 b, at 50 light-years away inside the Cetus constellation. Doyon with team’s JWST observations show a shift from the once believed rocky “super-Earth” six-times the size of our planet, to a distinct oddball; or, maybe, an eyeball.