“`html

An illustration showing four verified protoplanets circling the star V1298 Tau(Image credit: Astrobiology Center, NINS)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Space scientists have obtained a unique look at four infant planets as they mature, revealing something unexpected: these young worlds become less weighty as they get older.

These four worlds travel in closely confined orbits around the star V1298 Tau, a youthful system a mere 20 million years old (compared to our sun’s 4.5 billion years), positioned roughly 350 light-years away from our planet. A recent examination, relying on ten years of observations, suggests that the planets are unusually light, displaying feeble densities; in reality, they’re so enlarged that scientists have compared them to Styrofoam.

You may like

-

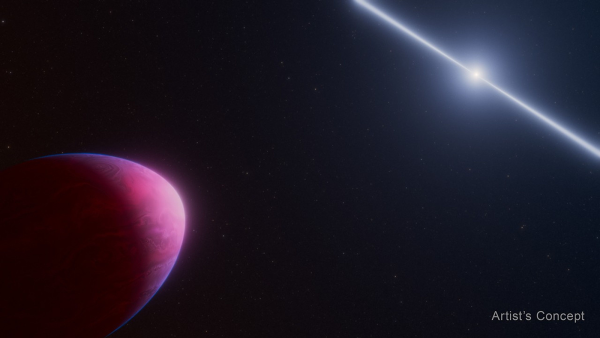

Astronomers discover bizarre ‘runaway’ planet that’s acting like a star, eating 6 billion tons per second

-

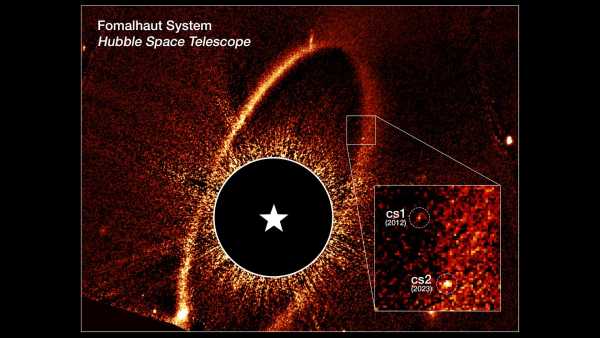

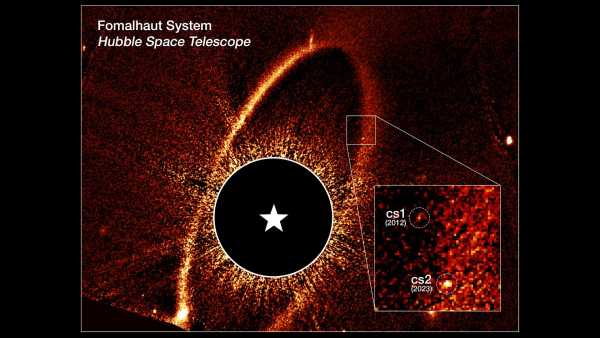

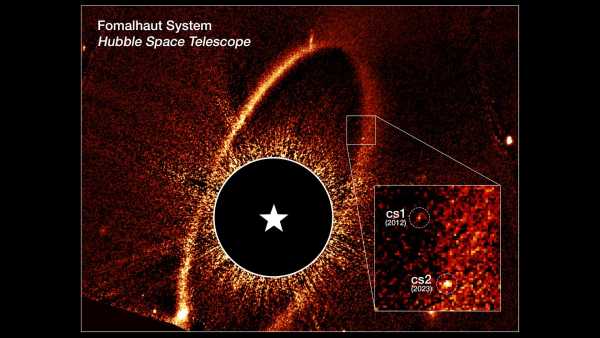

‘Unprecedented’ protoplanet collision spotted in ‘Eye of Sauron’ star system just 25 light-years from Earth

-

James Webb telescope uncovers a new mystery: A broiling ‘hell planet’ with an atmosphere that shouldn’t exist

Those more mature systems frequently teem with planets ranging from the size of Earth to that of Neptune, all in constricted, Mercury-esque orbits. The origins of these bodies have remained one of astronomy’s continuous enigmas.

“What’s genuinely captivating is that we are witnessing a glimpse of what will evolve into a very common planetary arrangement,” stated study principal author John Livingston, an associate professor at the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. “We’ve never before seen such a precise representation of them as they take shape.”

With time, the swollen planets orbiting V1298 Tau are predicted to diminish as they eliminate their thick gaseous envelopes, eventually becoming super-Earths and sub-Neptunes, which are planetary categories absent within our own solar system but prevalent throughout the galaxy.

By observing the planets during such a vital stage of development, the research, which appeared in the journal Nature on Jan. 7, allows astronomers to follow the disorganized procedures that mold planetary arrangements over the course of billions of years.

‘I couldn’t believe it!’

The quartet of planets that orbit V1298 Tau were initially spotted in 2019 within information obtained by NASA’s Kepler space telescope. One approximates the dimensions of Jupiter, whereas the remaining three fall in size between Neptune and Saturn.

What promptly distinguished the system was its packed configuration involving several oversized planets located within relatively tight orbits, an arrangement identified in only one other system, Kepler-51, among over 500 known multi-planet systems.

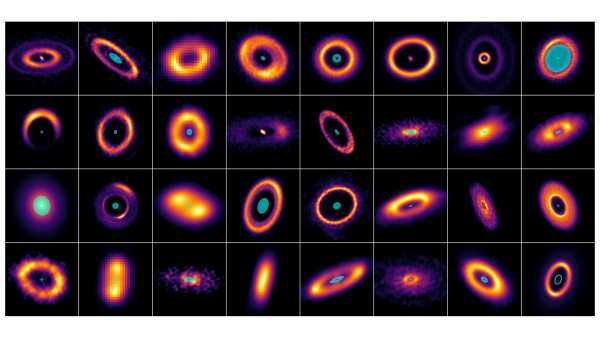

A compilation of planet-generating disks visible in 32 young star systems. The new exploration yields insights concerning how and when nascent planets develop.

While the planets’ presence was established, their underlying characteristics remained ambiguous. To identify them, Livingston and his team launched a roughly ten-year observational project employing six space-based and ground-based telescopes. They monitored the planets as they moved in front of their star, events termed transits, which trigger minimal light diminutions that expose a planet’s size and its orbital duration.

You may like

-

Astronomers discover bizarre ‘runaway’ planet that’s acting like a star, eating 6 billion tons per second

-

‘Unprecedented’ protoplanet collision spotted in ‘Eye of Sauron’ star system just 25 light-years from Earth

-

James Webb telescope uncovers a new mystery: A broiling ‘hell planet’ with an atmosphere that shouldn’t exist

Notably, subtle variations in the timing of these transits, arising from the planets gravitationally pulling each other, enabled the team to assess their mass. The approach is particularly effective owing to its immunity from the stellar flare disturbance often seen around juvenile stars, the study noted.

However, the method is viable only when scientists know each planet’s exact orbital period and this was missing for V1298 Tau e, the outermost planet. Only a pair of its transits had been previously seen, parted by a span of 6.5 years from Kepler and NASA’s exoplanet-observing Transiting Exoplanet Survey Satellite (TESS) telescope, leaving scientists uncertain of the quantity of transits that went undocumented in between, according to the study.

A surge of fortune came about when the Las Cumbres Observatory ground-based network, equipped with telescopes in the United States, Chile, and South Africa, observed a third transit. This ultimately enabled the researchers to establish the planet’s orbit and simulate the whole system’s gravitational interaction.

“I couldn’t believe it!” said study co-author Erik Petigura, an astronomy and astrophysics associate professor at UCLA. “The timing was so uncertain that I thought we would have to try half a dozen times at least. It was like getting a hole-in-one in golf.”

The findings indicated that notwithstanding their radius being five to ten times that of Earth, the planets possessed a mass only five to fifteen times greater than Earth’s, categorizing them among the least dense planets identified to date, said Livingston.

“By assessing the weight of these planets for the first time, we have presented the opening observational validation,” stated study co-author Trevor David, an astrophysicist previously with the Flatiron Institute in New York, who directed the system’s finding in 2019. “They are in fact, remarkably ‘puffy,’ yielding a vital, long-anticipated reference for theories surrounding planet evolution.”

related stories

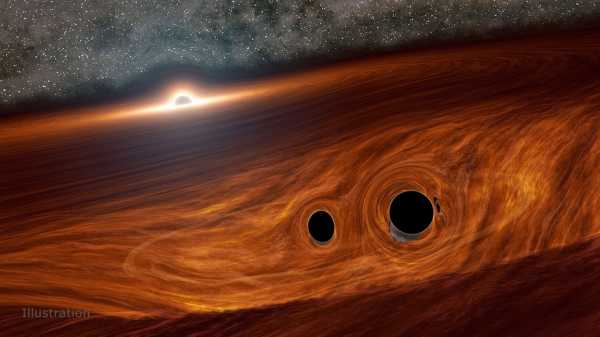

—James Webb telescope confirms a supermassive black hole running away from its host galaxy at 2 million mph, researchers say

—Some objects we thought were planets may actually be tiny black holes from the dawn of time

—Giant cosmic ‘sandwich’ is the largest planet-forming disk ever seen — Space photo of the week

Next, the team replicated the planets’ development and determined that they had already shed a significant amount of their original atmospheres, while also cooling off at a faster rate than traditional models predicted.

“But they’re still developing,” stated study co-author James Owen, an astrophysics associate professor from Imperial College London. He anticipates that the planets will continue releasing gas and shrinking into super-Earths and sub-Neptunes.

“Throughout the coming several billion years, they will persist in shedding their atmospheres and considerably shrinking, converting into the compact super-Earth and sub-Neptune systems we witness around the galaxy,” Owen added.

Sharmila KuthunurSocial Links NavigationLive Science contributor

Sharmila Kuthunur is a freelance space journalist residing in Bengaluru, India. She has also contributed to Scientific American, Science, Astronomy and Space.com, and other publications. She earned a master’s degree in journalism from Northeastern University located in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

Astronomers discover bizarre ‘runaway’ planet that’s acting like a star, eating 6 billion tons per second

‘Unprecedented’ protoplanet collision spotted in ‘Eye of Sauron’ star system just 25 light-years from Earth

James Webb telescope uncovers a new mystery: A broiling ‘hell planet’ with an atmosphere that shouldn’t exist

‘What the heck is this?’ James Webb telescope spots inexplicable planet with diamonds and soot in its atmosphere

‘Not so exotic anymore’: The James Webb telescope is unraveling the truth about the universe’s first black holes