“`html

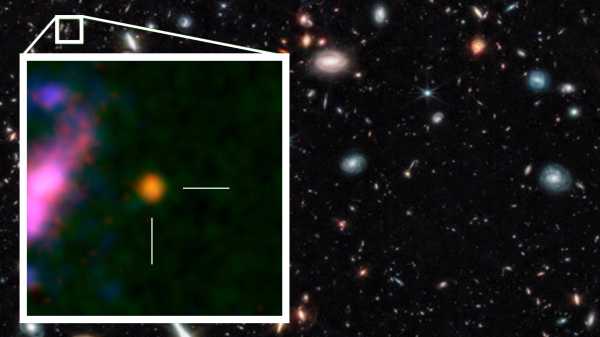

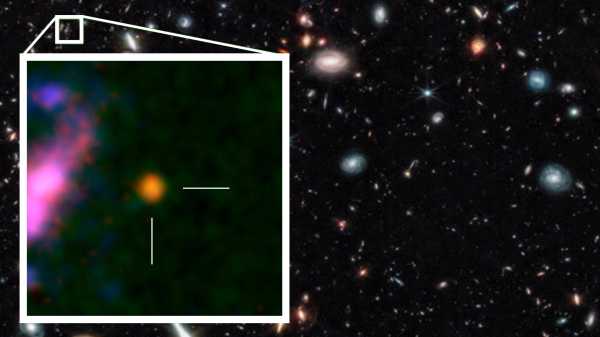

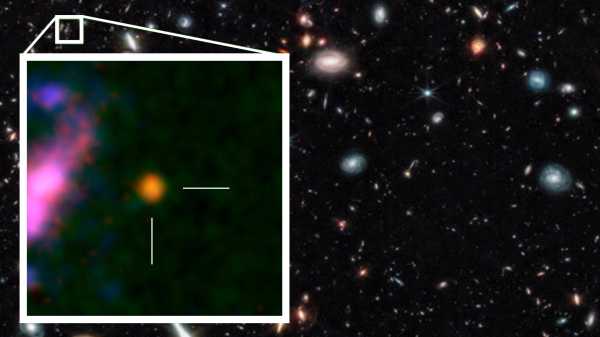

The James Webb telescope has provided an up-close inspection of the structures encompassing a supermassive black hole (inset), revealing extraordinary detail. A depiction from the Hubble telescope (background) offers the broader astronomical framework.(Image credit: NASA, ESA, CSA, Enrique Lopez-Rodriguez (University of South Carolina), Deepashri Thatte (STScI); Image Processing: Alyssa Pagan (STScI); Acknowledgment: NSF’s NOIRLab, CTIO)ShareShare by:

- Copy link

- X

Share this article 0Join the conversationFollow usAdd us as a preferred source on GoogleNewsletterSubscribe to our newsletter

Space experts have unveiled the sharpest depiction to date from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) of the environment surrounding a black hole. The incredible sight might aid in resolving a mystery spanning decades, while also overturning an established idea regarding the most extreme entities in space.

From the nineties onward, space observers have spotted a strange luminosity in infrared wavelengths enveloping the active supermassive black holes (SMBHs) found in some galaxy centers. Previously, they tied these infrared emissions to outflows — extremely heated streams of material projected outwards from black holes.

You may like

-

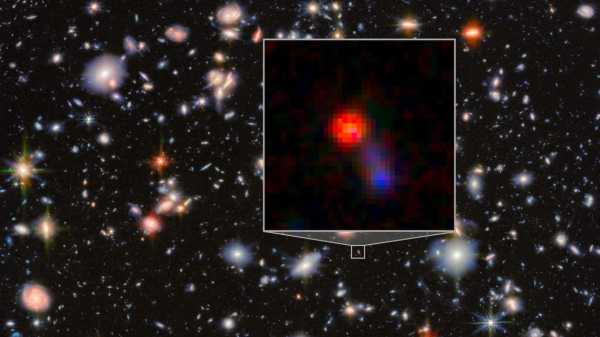

James Webb telescope might have detected the most ancient, farthest black hole documented to date

-

James Webb telescope locates supermassive black hole concealed within ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ galaxy

-

‘Not so exotic anymore’: The James Webb telescope is revealing truths about the universe’s earliest black holes

The information provided by JWST, combined with many ground-based observations, shows that the infrared abundance comes from the dusty disk that’s being drawn towards the Circinus galaxy’s core SMBH, rather than from matter ejected from it.

This cosmic discovery might allow space experts to gain a more comprehensive insight into the development and progression of SMBHs, together with the effect these immense dark phenomena exert on the galaxies that host them.

Of doughnuts and disks

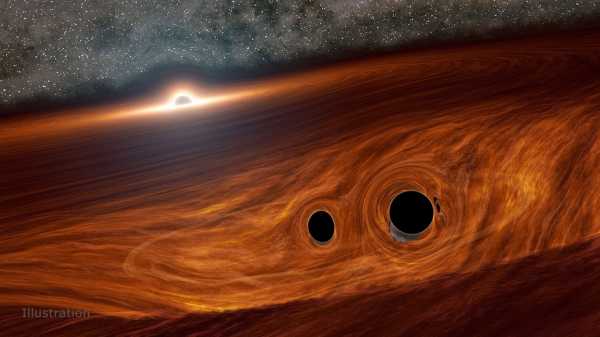

Active black holes, such as the ones found in galactic centers, receive matter via a massive loop of inflowing gas and dust. As the black hole pulls matter from the inner boundary of this “doughnut,” referred to as a torus, the material takes the form of a thinner accumulation disk that spirals inward towards the black hole, similarly to liquid going down a drain.

A portrayal of a supermassive black hole emitting a powerful outburst into space

The gravitational forces of the black hole increase the velocity of the inflowing matter to very high speeds. The subsequent resistance inside the disk prompts the swirling material to produce light that glows so vibrantly that it obstructs the view of space experts into the inner region encircling the black hole.

However, black holes don’t act as perfect vacuums, and have limitations on feeding. Consequently, they return a portion of the spinning material back out into space, in the form of jets or “winds.” With this in mind, having insight into the attributes of a black hole’s torus, accretion disk and outflows holds significance for comprehending the way black holes of varying dimensions accumulate and eject matter, with the possibility of influencing their host galaxies via suppressing or boosting star creation over large galactic distances.

Resolving a long-standing mystery

Previously, the compact gas and intense starlight in Circinus made it difficult for space experts to closely observe the galaxy’s main area and SMBH.

“To study the supermassive black hole, despite not being able to individually make it out, they needed to obtain the entire intensity of the galaxy’s interior section across a wide range of wavelengths, and then put that data into models,” noted Enrique Lopez-Rodriguez, the study’s primary author and a galaxy development researcher at the University of South Carolina, in comments shared by NASA.

You may like

-

James Webb telescope might have detected the most ancient, farthest black hole documented to date

-

‘Not so exotic anymore’: The James Webb telescope is revealing truths about the universe’s earliest black holes

-

James Webb telescope verifies a supermassive black hole fleeing its home galaxy at 2 million mph, report researchers

Past models independently analyzed the observed spectra of the torus, accretion disk and outflows, though they weren’t capable of resolving the area in totality. As such, space experts weren’t able to define which element of the SMBH’s surroundings led to the overabundance of infrared light.

JWST’s cutting-edge capabilities enabled scientists to observe through the dust and starlight of Circinus, allowing them to achieve a more precise view of the SMBH’s environment. They accomplished this by employing an imaging method referred to as interferometry.

In general, ground-based interferometry relies on a sequence of telescopes or mirrors that act together to gather and synthesize light from an astronomical subject over an extensive region. Synthesizing light from various origins results in the electromagnetic waves generating that light to cause interference patterns, which experts can then analyze to determine the sizes, shapes and other characteristics of such subjects.

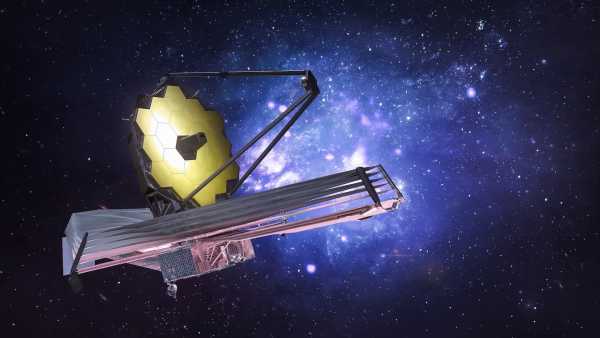

Differing from ground-based facilities, however, the space-situated JWST has the capacity to function as its individual interferometer array via its aperture masking interferometer (AMI), a piece of equipment within the telescope’s Near-Infrared Imager and Slitless Spectrograph (NIRISS) instrument. Similar to a camera’s aperture, AMI takes the form of an opaque physical mask containing seven small, hexagonal openings to regulate the quantity and path of light entering JWST’s sensors.

On the whole, AMI essentially duplicates JWST’s resolution. “This allows us to view images with double the clarity,” relayed Joel Sanchez-Bermudez, an astrophysicist associated with the National University of Mexico and one of the study’s authors, in the released statement. “As opposed to Webb’s 6.5-meter [21 feet] width, it’s like we are watching this region from a 13-meter space telescope.”

By improving its resolution twofold, JWST captured its most detailed look so far at a region measuring 33 light-years across at the core of Circinus. This unique image enabled the scientists to compute that a majority, approximately 87%, of the excessive infrared emissions stem from the dusty disk dynamically nourishing the central black hole; “the inner surface of the hole of the doughnut,” according to Lopez-Rodriguez via email. Despite earlier findings implying that the excess may have derived from warm dusty winds, or even the galaxy’s remaining starlight, the team determined that less than 1% of such emissions originate from the dynamic outflows that are flowing away from the SMBH.

The accretion might be halting star creation at Circinus’ center; however, verifying this will require different types of JWST-based viewing, Lopez-Rodriguez explained.

An invaluable perspective

A rendering displaying the James Webb Space Telescope circling in orbit

Aside from revealing previously concealed SMBH workings, this investigation highlights the prospective utility of JWST-centered interferometry in scrutinizing diverse astronomical entities, which include more active SMBHs present within the core of adjacent galaxies. Experts aim to increase sample sizes, to ascertain if infrared emissions from other SMBHs result from their dusty disks or their warm outflows.

related stories

— James Webb telescope discovers earliest black hole in known universe, spotting it ‘as far back as realistically possible’

— James Webb telescope spots supermassive black hole concealed inside ‘Jekyll and Hyde’ galaxy

— James Webb telescope discovers something ‘very exciting’ expelling from first black hole ever imaged

“To gain coveted JWST usage, AMI needs to be used on objectives that cannot be done from ground-based observation, or at wavelengths restricted by Earth’s atmosphere,” stated Julien Girard, the study co-author and a senior researcher functioning at the Space Telescope Science Institute, to Live Science through email.

AMI-centered observations can enhance the understanding of our own solar system; they recently afforded us a detailed glimpse of the volcanoes on Io, one of Jupiter’s hellish moons, added Girard. So AMI holds the capacity to observe a wide range of cosmic entities of different configurations and sizes, from lunar bodies flowing with lava to black holes concealed by dust. Moving forward, it could aid space experts in identifying moons orbiting noticeable asteroids, or uncovering the paths and magnitudes of multistar configurations, Girard appended.

Ivan FarkasLive Science Contributor

Ivan is a long-tenured writer who is keen on gaining insight into technology, past events, societal nuances, in tandem with virtually every principal “ology” from “anthro” to “zoo.” Ivan also dabbles in web-based comedy, advertising and marketing material, and industry-oriented review articles. Being an exercise science major, whenever Ivan isn’t absorbed by a book or screen, he’s likely enjoying the outdoors or repeatedly lifting progressively heavier things off the ground. Ivan was born in the sunny landscapes of Romania, and now lives in the even-sunnier state of California.

Show More Comments

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.

LogoutRead more

James Webb telescope might have detected the most ancient, farthest black hole documented to date

‘Not so exotic anymore’: The James Webb telescope is revealing truths about the universe’s earliest black holes

James Webb telescope verifies a supermassive black hole fleeing its home galaxy at 2 million mph, report researchers

James Webb telescope