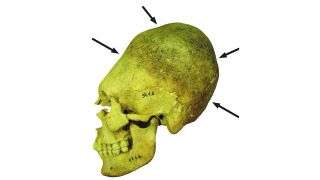

Artificially deformed skull of an adult woman. Permanent binding during childhood caused the elongation of the braincase and depressions in the bone.

Over decades, dozens of artificially deformed “alien-like” skulls that are more than 1,000 years old have been unearthed in a cemetery in Hungary. Now, these skulls are revealing how the collapse of the Roman Empire unleashed social changes in the region.

During the fifth century A.D., people in central Europe practiced skull binding, a practice that dramatically elongates head shapes. These altered skulls were so drastically deformed that some have compared them to the heads of sci-fi aliens. The fifth century was also a time of political unrest, as the Roman Empire collapsed and people in Asia and eastern Europe were displaced by invading Huns, a nomadic Asian group.

A graveyard in Mözs-Icsei dűlő, Hungary, first excavated in 1961, held the largest collection of elongated skulls in the region. A new study pieces together how skull-binding communities co-existed with other cultures during times of political instability — and how the skull-stretching tradition may have been shared between groups.

The practice of artificially stretching heads by tightly binding them in childhood can be traced to the Paleolithic era and has persisted to modern times, lead study author Corina Knipper and co-authors István Koncz, Zsófia Rácz and Vida Tivadar told Live Science in an email. Skull binding spread across central Asia in the second century B.C., expanded into Europe around the second and third centuries A.D. and became increasingly popular in central Europe by the first half of the fifth century A.D., according to the authors.

“The site of Mözs that we studied represents this time period and is an excellent example of a community in which the custom was very common,” the co-authors said.

For the new study, researchers examined 51 elongated skulls from burials in the Mözs graveyard, in what was once a Roman province known as Pannonia Valeria. The graves, 96 in all, were divided into three groups and represented three generations, from A.D. 430 until the cemetery was abandoned in A.D. 470.

The first burial group is thought to be the founding group of the cemetery, and their remains are buried in Roman-style graves. A second group is buried in a style that appears to have originated outside the region, while the third group combines burial practices that draw from Roman and other traditions.

Individuals with artificially stretched skulls were found in all three burial groups, with elongated skulls comprising around 32% of the burials in the first group; 65% in the second group; and 70% in the third group. However, variations in the location and direction of grooves in the skulls suggest that different binding techniques were used among the groups.

Analysis of isotopes, or different versions of atoms, in the bones provided more clues about where individuals in the later burials came from. Some originated near Mözs and others settled there after being displaced. Finding people of different origins mingled together in a cemetery suggests that these groups were living together, establishing a community where cultural habits and customs that were once regional — such as diet or head-binding — were shared and adopted between groups in the waning days of the Roman Empire.

Previously, archaeologists had hypothesized that new arrivals to Pannonia Valeria settled with people who had lived there under the Romans, based on artifacts that were found in the graves; the new evidence confirms that, according to the study.

“The application of new technology — isotope analysis — helped enormously to comprehend community formation and lifestyle during the fifth century,” the study co-authors said. “We revealed information about diet and evidence that people actually moved, which would not have been accessible by classic anthropological and archaeological methods alone.”

The findings were published online today (April 29) in the journal PLOS ONE.

Sourse: www.livescience.com