A new study suggests that humanity may have reached the limit of average life expectancy. (Image credit: HUIZENG HU via Getty Images)

Life expectancy is increasing more slowly than it did in the 20th century, according to a new study of 10 developed countries.

During the 20th century, improvements in medicine and public health led to “massive gains in life expectancy,” with some of the longest-lived high-income countries seeing average life expectancy at birth increase by about three years each decade. These improvements in life expectancy were initially driven by falling infant mortality rates, followed by declines in middle-aged and older death rates. In the United States, for example, average life expectancy at birth was 47.3 years in 1900; by 2000, it had risen to 76.8 years.

However, new research suggests that the 21st century will not see a similar jump in life expectancy.

A report published Monday (October 7) in the journal Nature Aging suggests that over the next three decades, people will live just 2.5 years longer.

The most likely reason for this slowdown, the study authors say, is that humanity is approaching the upper limit of its life expectancy. In other words, as the number of people living to old age increases, the main mortality risks are linked to biological aging—the gradual accumulation of damage to cells and tissues that inevitably occurs over time. We know how to prevent measles from killing children, but we can’t yet stop the biological clock that continues ticking into our 60s, 70s, and beyond.

Tackling one aging-related disease at a time — such as trying to develop drugs for Alzheimer’s or cancer — is like putting on a “band-aid for survival,” said Jay Olshansky, the study’s lead author and a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of Illinois at Chicago. These efforts to develop effective treatments — and eventually cures — may allow people to live to old age, but they don’t address the underlying problem of aging, he told Live Science.

In their new study, Olshansky and his team analyzed data on trends in life expectancy from 1990 to 2019. They examined national vital statistics data from nine regions with the highest life expectancy — Australia, France, Italy, Japan, South Korea, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, and Hong Kong. They also analyzed figures from the U.S., as some researchers had predicted significant increases in life expectancy in the country, they noted in their paper. The researchers then used this retrospective analysis to predict future changes in life expectancy that could occur this century.

The research team found that overall improvements in life expectancy have slowed in the 10 countries, especially since 2010. Current age groups have a low chance of living to 100: 5.1% for women and 1.8% for men.

Among children born in 2019, Hong Kong children had the highest probability of living to 100, with girls having a 12.8% chance of living to 100 and boys having a 4.4% chance of living to 100.

These results suggest that to further extend lifespan, more research needs to focus on gerontology, which is the biology of aging, not just the diseases associated with the process, Olshansky said. In this context, it is important to distinguish between lifespan and life expectancy, which is the maximum age a person can ever live to.

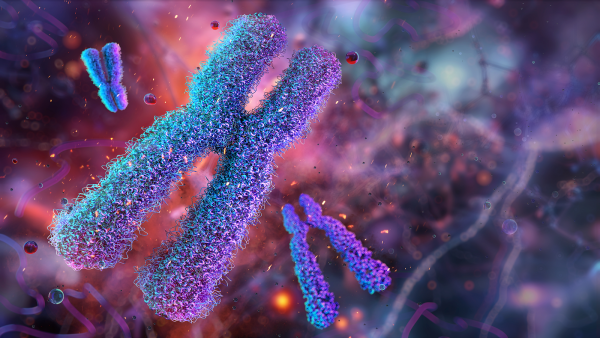

Research into ways to slow or reverse the cellular aging process could help people stay “younger” longer, Olshansky suggested. For example, scientists are working to develop drugs that could slow aging by lengthening the ends of chromosomes, known as telomeres, which typically shorten over time.

“Now we need to focus on production

Sourse: www.livescience.com