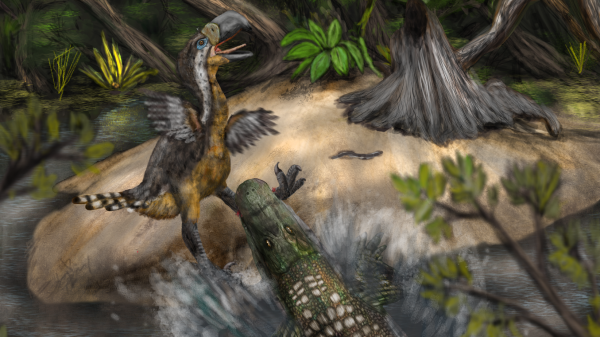

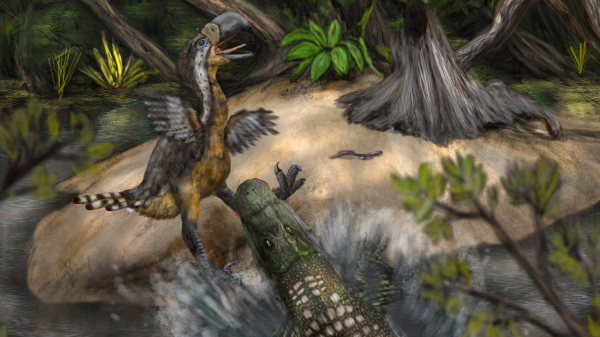

Fossil evidence suggests that the ancestors of giant birds like the rhea were likely capable of long-distance flight. (Image credit: Mikael Nigay/500px via Getty Images)

Ostriches, emus, rheas and other large flightless birds inhabit six landmasses separated by oceans, but how they reached such distant locations without the ability to fly remains an enduring mystery.

One idea was that the ancestors of this group of birds, known as paleognaths, simply came to these areas when much of the planet was united into the supercontinent Pangea (320–195 million years ago), and that when this giant landmass split apart, the birds were already there.

You may like

-

Why are giant moas—birds that once towered over humans—even harder to resurrect than dire wolves?

-

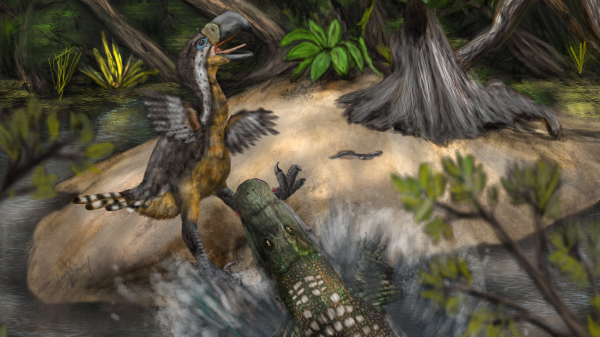

Bite marks suggest that the giant terror birds may have been potential prey for another predator – the enormous caiman.

-

The 14 Largest Birds on Earth

To find out what happened, Clara Widrig, a vertebrate zoologist at the Smithsonian's National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., and her colleagues analyzed a specimen of the ancient paleognath Lithornis promiscuous. Although it lived approximately 59–56 million years ago, it is the oldest paleognath fossil found in such a pristine state.

“We can't say for sure whether Lithornis was a direct ancestor of our living paleognaths—it's quite possible that the true ancestor hasn't been discovered yet—but this is our best guess at what that ancestor might have looked like,” Widrig told Live Science.

Previous studies of preserved feathers from a somewhat more distant relative of the lithornithid, Calciavis grandei, suggested that it could fly, but it was unclear how far. No one had conducted a quantitative analysis of the lithornithid's bone shape to answer this question.

So, in a new study published Wednesday (September 17) in the journal Biology Letters, Widrig and her colleagues compared the shape of L. promiscuous's sternum (breastbone) to those of modern birds and used a 3D geometric dataset to figure out how well the animal could fly.

“The sternum is very important for flight because it's where the large pectoral muscles, which are responsible for flight, attach,” Widrig said.

The shape of the sternum indicated that it could perform a range of aerobic, flapping flight styles, allowing for long flights.

You may like

-

Why are giant moas—birds that once towered over humans—even harder to resurrect than dire wolves?

-

Bite marks suggest that the giant terror birds may have been potential prey for another predator – the enormous caiman.

-

The 14 Largest Birds on Earth

“We found that the shape of the sternum is very similar to the shape of the sternum of modern birds that can fly very long distances across oceans, such as great egrets and herons,” Widrig said.

“This is very interesting because the great egret is a cosmopolitan species, as it travels from continent to continent,” said Peter Hosner, curator of birds at the Natural History Museum of Denmark, who was not involved in the work.

“In reality, such species are quite rare in birds,” he told Live Science. “In the Northern Hemisphere, where many birds are migratory and travel long distances, we have biased estimates. But overall, most birds live on a single continent, island, or small area and don't move very often.”

The find suggests that ancient paleognaths may have migrated to distant lands and founded populations that subsequently evolved independently into the large, generally flightless birds we know today.

“It looks like a spectacular case of convergent evolution,” Hosner said.

There are approximately 60 species of living paleognaths today. Among them are about 45 species of tinamou (which can fly in short bursts, like pheasants), up to five species of kiwi, one species of emu, three species of cassowary, two species of ostrich, and one or two species of rhea, Widrig said.

“For a bird to stop flying, two conditions must be met,” she said. “It must be able to obtain all its food on the ground, meaning it must not rely on food growing in trees, for example. And there must be no predators from which it would have to flee.”

In more recent times, according to Widrig, this only occurred in island environments without predators, such as the dodo (Raphus cucullatus). But after the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event about 66 million years ago, which wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs, everything changed.

RELATED STORIES

— Why don’t all birds fly?

“It was a clear human attack on the species”: the fate of the great auk

— Southern cassowary: a giant prehistoric bird with dinosaur feet

“The world was largely devoid of predators, and mammalian predators hadn't yet evolved, so any ground-feeding bird had the opportunity to essentially become flightless,” Widrig said. “Flying is hard work, and it's much easier to become flightless if you don't have anything to escape from.”

When larger predators appeared, flightless birds had time to adapt, she said, either by becoming large and intimidating, like the cassowary, or by becoming fast runners, like the ostrich.

But all these similar changes evolved independently. “They didn't just sit down on the phone and say, 'Okay, you'll go to Africa and evolve into an ostrich. And I'll go to South America and evolve into a rhea,'” Widrig said.

Chris Simms, Live Science contributor

Chris Simms is a freelance journalist who previously worked at New Scientist magazine for over 10 years, serving as editor-in-chief and assistant news editor. He was also a senior editor at Nature and holds a degree in zoology from Queen Mary, University of London. In recent years, he has written numerous articles for New Scientist and was shortlisted for the 2018 British Science Writers' Association Best Newcomer award.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be asked to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

Why are giant moas—birds that once towered over humans—even harder to resurrect than dire wolves?

Bite marks suggest that the giant terror birds may have been potential prey for another predator – the enormous caiman.

The 14 Largest Birds on Earth

Scientists have discovered that baby pterosaurs died during a powerful Jurassic storm 150 million years ago.

Kakapo: A fat parrot that can live for almost 100 years

The “Ash-Winged Dawn Goddess” is the oldest pterosaur ever discovered in North America. It was so small it could fit on a person's shoulder.

Latest news about birds

Best Bird Song Apps in 2025 – Identify Bird Songs and Improve Your Bird Knowledge

Kakapo: A fat parrot that can live for almost 100 years

Japanese Quail: A Bird with Strange Semen Foam, a Post-Sex Walk, and a Place in Space History

How do migratory birds know where they are going?

Southern cassowary: a giant prehistoric bird with dinosaur feet

Australia's 'trash parrots' have now created a local 'drinking tradition'

Latest news

The oldest known dinosaur with a domed head has been discovered protruding from a rock in Mongolia's Gobi Desert.

A 'rare' ancestor reveals how giant flightless birds reached distant lands.

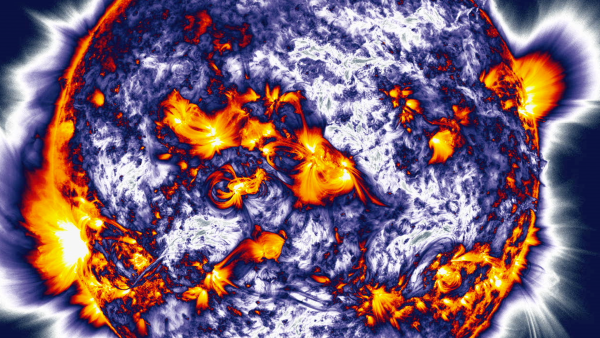

'The Sun is slowly waking up': NASA warns that extreme space weather could become even more extreme in the coming decades

Scientists have invented a new sunscreen made from pollen.

An anthropologist claims the hand positions on a 1,300-year-old Mayan altar have a deeper meaning.

A laboratory study shows that even short-term exposure to air pollution can cause inflammation of the placenta.

LATEST ARTICLES

1Even short-term exposure to polluted air can lead to inflammation of the placenta, laboratory studies show.

Live Science magazine is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web notifications

- Career

- Editorial standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-news-daily,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com