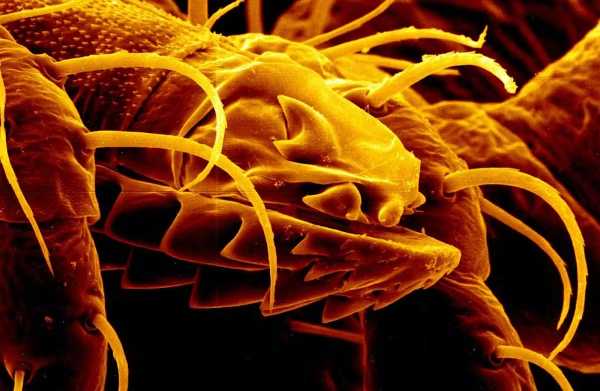

The deer tick, Ixodes scapularis, can transmit Lyme disease and other dangerous illnesses. (Image courtesy of the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention)

When you think of ticks, you probably picture the dreaded little parasites haunting you on weekend hikes or during an afternoon in the park.

Your concerns are well founded. Tick-borne infections are the most common vector-borne diseases, or illnesses transmitted by living organisms, in the United States. Each tick feeds on the blood of several animals throughout its life, ingesting viruses and bacteria and transmitting them with its next bite. Some of these viruses and bacteria are dangerous to humans, causing diseases that can be debilitating and sometimes fatal without treatment, such as Lyme disease, babesiosis, and Rocky Mountain spotted fever.

But every bite of this irritating, insatiable pest also contains a treasure trove of social, ecological and epidemiological history.

You may like

-

Hunter's rare allergy meant he could no longer eat red meat.

-

The earliest evidence of people catching diseases from animals dates back 6,500 years.

-

Remnants of ancient viruses make up 40% of our genome. They can cause brain degeneration.

In many cases, it is human actions in the distant past that have caused ticks to carry these diseases so widely today. This is what makes ticks interesting to environmental historians like me.

Changing forests have increased the risk of tick infestations

In the 18th and 19th centuries, settlers cleared more than half of the forest land in the northeastern United States, cutting down forests for timber and making way for farms, towns, and mining operations. The massive land clearing led to a dramatic decline in wildlife of all kinds. Predators such as bears and wolves, as well as deer, were driven out.

As agriculture moved west, people in the northeast began to recognize the ecological and economic value of trees, and they returned millions of acres to forests.

The forests grew again. Herbivores like deer returned, but the predators that once kept their populations in check were gone.

As a result, the deer population grew rapidly. Along with the deer came ticks (Ixodes scapularis), which carry Borrelia burgdorferi, the bacterium that causes Lyme disease. When a tick feeds on an infected animal, it can become infected with the bacterium. The tick can then pass it on to its next victim. In humans, Lyme disease can cause fever and weakness, and if left untreated, damage to the nervous system.

The deer tick (Ixodes scapularis), also known as the black-legged tick, is native to the eastern part of the country. It is one of many disease-carrying ticks in the United States.

The eastern United States has been a hotbed for tick-borne Lyme disease since about the 1970s. In 2023, Lyme disease was estimated to affect more than 89,000 Americans, and possibly more.

Californians Move into Tick Territory

Over centuries, changing human settlement patterns and land use policies have shaped the role of ticks and the diseases they carry in their environments.

You may like

-

Hunter's rare allergy meant he could no longer eat red meat.

-

The earliest evidence of people catching diseases from animals dates back 6,500 years.

-

Remnants of ancient viruses make up 40% of our genome. They can cause brain degeneration.

In short, humans have created conditions for ticks to breed and diseases to spread among us.

California's northern interior coast and the Santa Cruz Mountains, which converge north and south on San Francisco, have never been clear-cut and are still home to predators like mountain lions and coyotes. But competition for space has pushed people deeper into the wilderness north, south, and east of the city, changing the ecology of ticks.

Western blacklegged tick range map.

While western black-legged ticks (Ixodes pacificus) typically swarm in large forest preserves, the bacteria that causes Lyme disease are actually more common in small, isolated patches of green vegetation. In these isolated areas, rodents and other tick hosts can thrive, protected from larger predators that require a larger habitat to roam freely. However, isolation and less diversity also mean that infections spread more easily within the tick host population.

People prefer to build individual homes on hillsides rather than large, interconnected complexes. As Silicon Valley expands south of San Francisco, this checkerboard pattern fragments the natural landscape, creating a difficult-to-manage public health threat.

Fewer hosts and denser host concentrations often mean proportionally more infected hosts and therefore a greater tick threat.

The tick's mouth is covered with barbs, which allows it to hold on for hours and drink blood.

The six counties within that boundary, all of which surround and include San Francisco, account for 44% of California's reported tick-borne disease cases.

A Lesson from Texas Cattle Ranching

Livestock have also impacted the disease threat posed by ticks.

In 1892, at a cattle convention in Austin, Texas, Dr. B. A. Rogers presented a new theory that ticks were the cause of the recent devastating Texas rinderpest epidemics. The disease had been brought in by cattle imported from the West Indies and Mexico in the 17th century and had caused enormous losses to livestock. But how the disease spread to new victims remained a mystery.

Editors of Daniel's Texas Medical Journal found the idea that ticks spread disease laughable and ridiculed the hypothesis by publishing a satirical article about what they called an “advance copy” of a forthcoming report on the topic.

“The tick's fluid secretion is believed to be a fever-causing poison… [and since the tick] is known to chew tobacco like all other Texans, its secretion is likely tobacco juice,” they wrote.

Fortunately for the cattle ranchers, not to mention the cows, the USDA sided with Rogers. Its rinderpest tick control program, launched in 1906, curbed rinderpest outbreaks by limiting where and when cattle crossed tick-infested areas.

Swollen ticks feed on the calf's ear.

By 1938, the government had established a 580-by-10-mile quarantine zone along the U.S.-Mexico border in a tick-friendly area of South Texas.

Through this innovative use of natural space as a public health tool, rinderpest had been completely eradicated from 14 southern states by 1943.

Ticks are products of their environment.

When it comes to tick-borne diseases, location matters around the world.

Take, for example, the predatory tick (Hyalomma spp.), found in the Mediterranean and Asia. As juveniles, or nymphs, these ticks feed on small forest animals such as mice, hares, and voles, but as adults they prefer livestock.

For centuries, this tick was an occasional nuisance to nomadic herders in the Middle East. But in the 1850s, the Ottoman Empire passed laws forcing nomadic tribes to settle down to farming. Unclaimed land, especially on the forested edges of the steppes, was offered to settlers, creating ideal conditions for the hunting ticks.

As a result, farmers in what is now Turkey have faced a surge in tick-borne diseases, including the virus that causes Crimean-Congo haemorrhagic fever, a potentially fatal disease.

RELATED STORIES

– Your skin should be toxic to ticks. Here's why it isn't.

— In the United States, several species of ticks can carry allergies to red meat, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

—Tick-borne diseases are on the rise. Here's how to protect yourself.

It might be asking too much for sympathy for the ticks you encounter this summer. They are, after all, blood-sucking parasites.

However, it is worth remembering that ticks are not to blame for their viciousness. Ticks are a product of the environment, and humans have played a significant role in turning them into the dangerous parasites that plague us today.

This edited article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

TOPICS parasites of deforestation

Sean Lawrence, Associate Professor of History, West Virginia University

Sean Lawrence is a historian of environmental history and modern Germany, with research in empire, ecology, rurality, and political economy.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be prompted to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

Hunter's rare allergy meant he could no longer eat red meat.

The earliest evidence of people catching diseases from animals dates back 6,500 years.

Remnants of ancient viruses make up 40% of our genome. They can cause brain degeneration.

A tourist picked up a poisonous snake and died after the bite triggered a rare allergic reaction, authorities say.

New viruses found in bats in China

Man's preference for 'soft' bacon may have caused his brain to become infected with worms

Latest news about viruses, infections and diseases

Have you gotten the COVID vaccine this year?

“We have effectively destroyed our entire capacity to respond to a pandemic,” says leading epidemiologist Michael Osterholm.

The first New World case of the parasitic blowfly in recent decades has been recorded in the United States.

Vaccines show promise in fight against dementia

COVID-19 vaccines for children in limbo due to conflicting federal recommendations

Legionnaires' disease outbreak in New York City has led to two deaths

Latest opinions

'Your concerns are well founded': How human activity has increased the risk of tick-borne diseases like Lyme disease

How the surface you exercise on can increase your risk of cramping

'Serious Negative and Unintended Consequences': Polar Geoengineering Is Not the Answer to Climate Change

Robert Kennedy Jr. Wants to Reform the Nation's 'Vaccine Court.' Here's What's Stopping Him

Dissecting (many) false claims by RFK Jr. about COVID vaccines

Scientific objectivity is a myth. Here's why

LATEST ARTICLES

1Chinese Scientists Search for Alien Radio Signals in 'Potentially Habitable' TRAPPIST-1 System

Live Science is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web Notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type_opinion,type-crosspost,exclude-from-syndication,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com