Paul Gelsinger, Jesse Gelsinger's father, testifies at a 2007 Senate Public Health Subcommittee hearing on the health concerns associated with gene therapy. (Image courtesy of Douglas Graham via Getty Images)

Milestone: First reported death due to gene therapy

Date: September 17, 1999

Where: University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia

Who: Jesse Gelsinger

Twenty-six years ago, on September 17, a teenager who underwent experimental gene therapy died. His death led to necessary changes in the clinical trial process, but also fueled skepticism that ultimately hindered the development of gene therapy for many years.

About 90% of infants with the most severe form of OTC deficiency die. However, Gelsinger, who had a milder, “late-onset” form of the disease, reached adulthood by strictly following a low-protein diet and taking 50 tablets a day to lower blood ammonia levels and neutralize its effects. Although Gelsinger was small for his age and suffered a dangerous ammonia crisis after stopping the tablets, he was otherwise healthy.

You may like

-

8-year-old with rare fatal disease shows dramatic improvement after experimental treatment

-

Experimental high cholesterol treatment edits DNA in the body to lower LDL levels

-

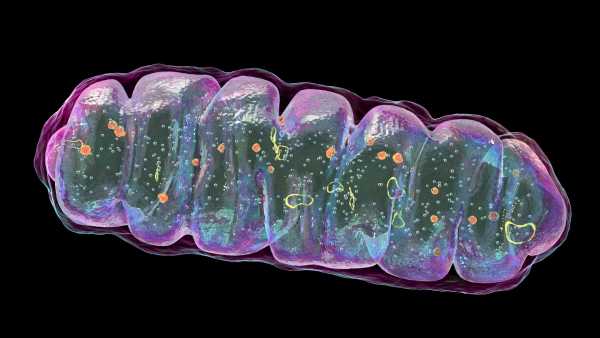

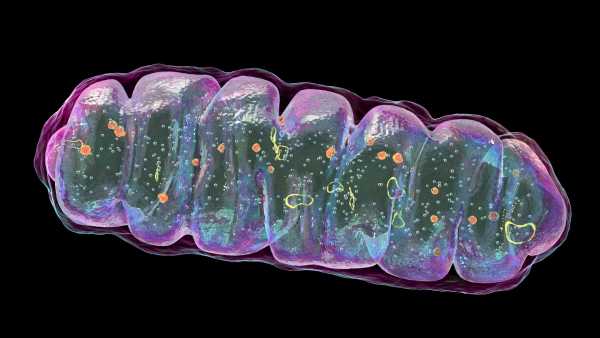

8 Children Saved From Potentially Deadly Inherited Diseases Thanks to New IVF Study Using 'Mitochondrial Donation'

Gelsinger wanted to help babies with the disease, so he enrolled in a safety study of a gene therapy designed to correct the defective OTC gene. The treatment used a weakened form of adenovirus, a type of cold virus, to deliver a corrected form of the OTC gene into Gelsinger's cells.

Gelsinger flew to the University of Pennsylvania, where the study was being conducted, and on September 13, 1999, the drug was injected into the artery supplying his liver. That day, as expected, he developed flu-like symptoms. But the next day, he developed jaundice, a severe inflammatory reaction, and a bleeding disorder, and his organs began to fail. He was taken off life support around 2:30 PM on September 17. An investigation revealed that his death was due to a severe immune reaction to the virus used to administer the drug.

According to The New York Times, an investigation by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) uncovered numerous problems with Gelsinger's inclusion in the study. First, he had impaired liver function and high blood ammonia levels when the study began. Second, the team failed to inform the patients that laboratory animals had died from higher doses of the drug before the study began. Furthermore, other study participants experienced serious side effects. Meanwhile, Dr. James Wilson, the lead researcher, owned shares in Genovo, the company developing the drug, and stood to receive millions if the therapy was successful.

James Wilson was the lead investigator in a gene therapy study for an over-the-counter drug. This study, like other gene therapy studies at the University of Pennsylvania, was halted after Gelsinger's death. Wilson continued his work in the field and has since participated in the development of several gene therapy drugs, including those for spinal muscular atrophy and an inherited form of blindness.

“We don't know what the consequences of these deviations are,” Dr. Katherine Zoon, then director of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, said at the time, as reported by The New York Times. “But they are important.”

Gelsinger's father, Paul Gelsinger, filed a wrongful death lawsuit against the parties involved in the lawsuit; the suit was eventually settled for an undisclosed amount.

Gelsinger’s death led to a series of changes in how gene therapy clinical trials are conducted and stricter informed consent requirements. All gene therapy trials at the University of Pennsylvania were suspended. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) also began requiring stricter monitoring of gene therapy trials.

Death cast a shadow over the field, and as public and private funding dried up, gene therapy stalled. However, thanks to advances in understanding the viral vectors used to deliver gene therapy, and later, the advent of the gene-editing tool CRISPR, the field was eventually revived.

Scientists are already using gene therapy to treat many rare genetic diseases, including severe combined immunodeficiency and multiple forms of blindness. The first CRISPR-based gene therapy, which treats sickle cell anemia by silencing a specific gene, was approved in January 2024. And in 2025, scientists announced the use of a customized CRISPR method, designed to target a specific gene mutation, to treat a child with a rare and devastating genetic syndrome.

RELATED STORIES

— A gene that human ancestors lost millions of years ago may help treat gout.

—American child receives first-ever personalized treatment for genetic disease using CRISPR.

—In the first case, congenital deafness in adolescents and adults was treated with new gene therapy.

Currently, the number of approved gene therapy drugs is small. Many of these approved treatments use cells edited in the laboratory and then reintroduced into the body to fight or treat cancer, rather than altering genes in the nuclei of the patient's own cells.

However, the field has come a long way since Gelsinger's death, and in 2021, scientists successfully used gene therapy to treat OTC deficiency.

Tia GhoseSocial Links NavigationEditor-in-Chief

Tia is the editor-in-chief and formerly a senior writer at Live Science. Her work has appeared in Scientific American, Wired.com, and elsewhere. She holds a master's degree in bioengineering from the University of Washington, a certificate in science writing from the University of California, Santa Cruz, and a bachelor's degree in mechanical engineering from the University of Texas at Austin. Tia was part of the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel team that published the “Empty Cradles” series on preterm births, which won multiple awards, including the Casey Medal for Distinguished Journalism in 2012.

You must verify your public display name before commenting.

Please log out and log back in. You will then be prompted to enter a display name.

Exit Read more

8-year-old with rare fatal disease shows dramatic improvement after experimental treatment

Experimental high cholesterol treatment edits DNA in the body to lower LDL levels

8 Children Saved From Potentially Deadly Inherited Diseases Thanks to New IVF Study Using 'Mitochondrial Donation'

An innovative drug for the treatment of cystic fibrosis that extends life by decades has earned its developers an “American Nobel Prize” of $250,000.

Remnants of ancient viruses make up 40% of our genome. They can cause brain degeneration.

Diabetic man produces his own insulin after genetically modified cell transplant

Latest news in genetics

Gene Lost by Human Ancestors Millions of Years Ago Could Help Treat Gout

Remnants of ancient viruses make up 40% of our genome. They can cause brain degeneration.

Scientists discover 'spirals' in DNA that form under pressure

Special protection may help human eggs stay fresh as the body ages

8 genomic hotspots linked to ME/CFS in largest study of its kind

Scientists claim humans may have untapped 'superpowers' in hibernation-related genes

Latest Features

The tragic death of gene therapy, which halted the field for a decade, was September 17, 1999.

History of Science: Gravitational Waves Discovered Proving Einstein Right – September 14, 2015

Volcanic 'eyeballs' peer into space from skull-shaped peninsula

James Webb's 'Starry Mountaintop' Could Be Observatory's Best Image to Date – Space Photo of the Week

Where is Queen Boudica buried?

A camera trap in Chile has captured strange lights flashing in the wild. Researchers are trying to explain them.

LATEST ARTICLES

1History of Science: The Tragic Death of Gene Therapy That Halted the Field for a Decade – September 17, 1999

Live Science is part of Future US Inc., an international media group and leading digital publisher. Visit our corporate website.

- About Us

- Contact Future experts

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility Statement

- Advertise with us

- Web Notifications

- Career

- Editorial Standards

- How to present history to us

© Future US, Inc. Full 7th Floor, 130 West 42nd Street, New York, NY 10036.

var dfp_config = { “site_platform”: “vanilla”, “keywords”: “type-regular,serversidehawk,videoarticle,van-enable-adviser-

Sourse: www.livescience.com