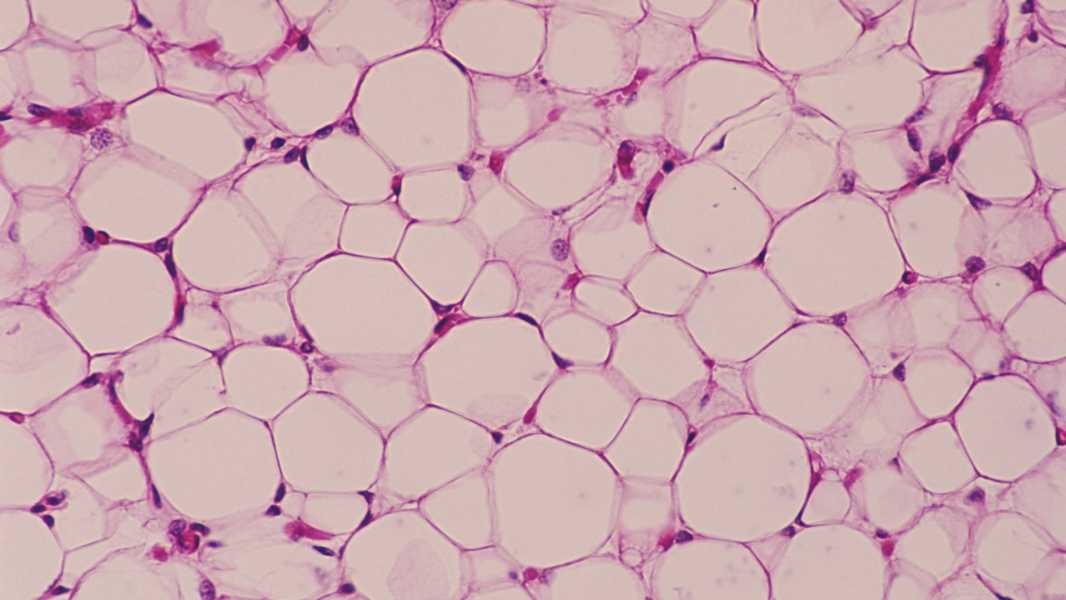

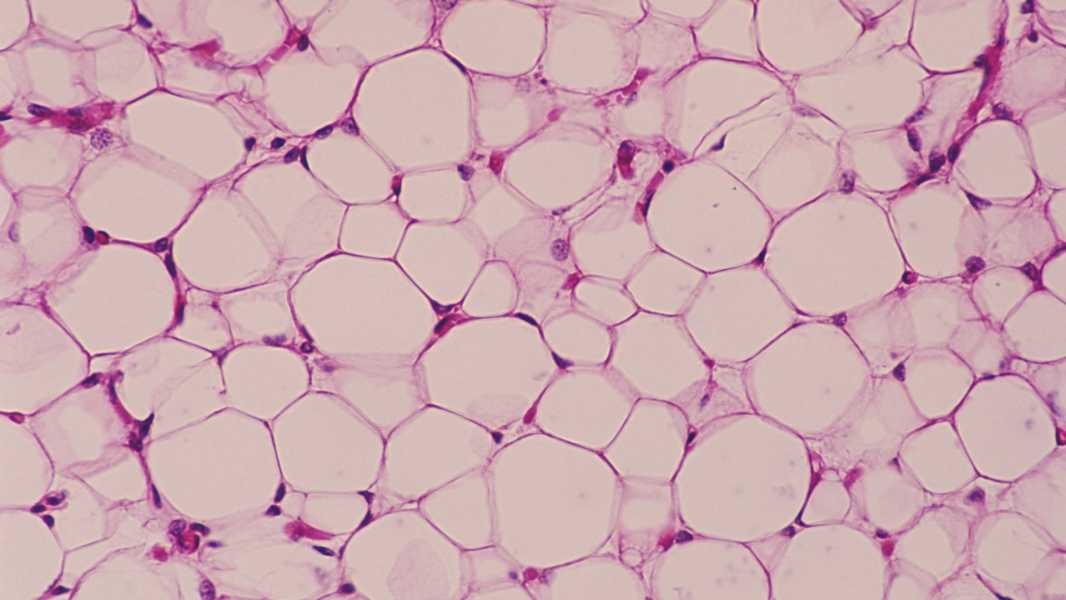

New research suggests that fat cells do more than just store energy. (Photo courtesy of Ed Reschke via Getty Images)

Scientists have identified unusual subtypes of fat cells in the human body and, after studying their functions, have concluded that these cells may play a role in the development of obesity.

The discovery could lead to new treatment approaches aimed at mitigating the effects of obesity, such as inflammation or insulin resistance, according to a study published Jan. 24 in the journal Nature Genetics.

“Identifying these [fat] subtypes is a real discovery,” study co-author Esti Yeager-Lotem, a professor of computational biology at Ben-Gurion University of the Negev, told Live Science. “It opens up a lot of possibilities for future research.”

The study's findings suggest that fat cells are “more diverse and complex than we previously thought,” Daniel Berry, a professor of nutrition at Cornell University who was not involved in the study, told Live Science in an email.

Over the past decades, research has shown that fat tissue serves much more than just storing excess energy. For example, fat cells known as adipocytes interact with immune cells, communicating with the brain, muscles, and liver. This, in turn, helps regulate appetite, metabolism, and body weight, and is involved in a variety of diseases associated with these processes.

“If something goes wrong in fat tissue, it affects other parts of the body,” says Jaeger-Lotem.

Not all fats are created equal

Scientists have also long established that excess fat is associated with an increased risk of various diseases. However, one aspect of obesity that puzzles experts is that not all fat is equally harmful.

Visceral fat — fat cells located in the abdomen near internal organs — is associated with a higher risk of various health problems than subcutaneous fat, which is the fat beneath the skin. For example, excess visceral fat has been linked to an increased risk of heart attack, stroke, diabetes, insulin resistance, and liver disease. Research also suggests that visceral fat is more “inflammatory” than subcutaneous fat, which may contribute to the poor health associated with obesity.

To better understand what's going on in fat tissue, Jaeger-Lotem and her colleagues created a “cell atlas” of adipocytes as part of the Human Cell Atlas, a global project that aims to map every cell in the human body.

The researchers built the atlas using single-nuclear RNA sequencing (snRNA seq), which measures gene activity by analyzing RNA, the molecular cousin of DNA. RNA molecules serve as blueprints for proteins, carrying instructions from DNA in the cell nucleus to sites where proteins are made. By measuring RNA in the nuclei of cells extracted from fat tissue, the team gleaned clues about the function of each cell within the tissue.

Jaeger-Lotem and her colleagues examined samples of subcutaneous and visceral fat collected from 15 people undergoing elective abdominal surgery. Most of the adipocytes were fairly “classical” — their primary job was to store excess energy. However, a small proportion of the fat cells were “non-classical,” in that their RNA indicated they were performing functions not typically associated with fat cells.

Among these cells were “angiogenic adipocytes,” which contained proteins normally associated with blood vessel formation; “immune-associated adipocytes,” which produced proteins associated with immune cell function; and “extracellular matrix adipocytes,” which were associated with scaffold proteins that support cellular structures. These cell subtypes, found in both the visceral and subcutaneous tissues, were classified as “angiogenic adipocytes,” which were classified as “immune-associated adipocytes,” which were classified as “extracellular matrix adipocytes,” which were classified as “extracellular matrix adipocytes,” and “extracellular matrix adipocytes.”

Sourse: www.livescience.com