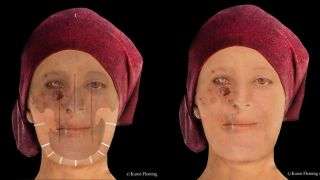

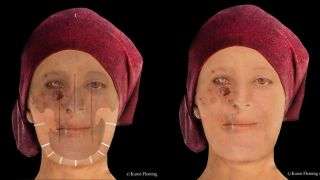

Leprosy mutilated the face of this high-status woman, who lived from the mid-15th to the 16th century in Scotland.

Leprosy mutilated her body more than 500 years ago, but this Scotish woman’s likeness isn’t lost to history; a new digital reconstruction of her face reveals what she looked like before her death at about age 40.

In a new project, forensic artists digitally reconstructed 12 faces from skulls found in a cemetery at St. Giles Cathedral in Edinburgh, Scotland, including the woman with leprosy, who may have been a tailor, and a man who was likely a peasant.

“We are revisiting a lot of old cases like this one, as we are very keen to put human faces on a lot of the human remains we have in our collections,” John Lawson, an archaeologist with the City of Edinburgh Council Archaeology Service, said in a statement. “Some of the remains date back to when Edinburgh became a royal burgh at the start of the 12th century, when St. Giles’ was first constructed.”

Related: Photos: See the Ancient Faces of a Man-Bun Wearing Bloke and a Neanderthal Woman

Archaeologists initially excavated the cathedral’s cemeteries in the 1980s and 1990s, ahead of a construction project and subsequent archaeological investigations. In all, the researchers found more than 100 burials dating from the 12th to the mid-16th centuries. The skeletons were then archived for future study.

However, only some of the human remains had an almost-complete skull, Karen Fleming, one of the two freelance forensic artists who worked on the project, told Live Science in an email.

The skulls from the 12th century were falling apart, “so the main challenge was to carefully attach the pieces of bone back together,” said Fleming, who is based in Scotland. “Many of the buried had bone problems, [for example] abscesses in the mouth, but one person in particular presented signs of suffering from leprosy.”

The woman with leprosy was likely between the ages of 35 and 40 when she died in the mid-15th to 16th century. The extent of her leprosy lesions suggests that she contracted the disease in adulthood, Fleming noted.

“She showed signs of lesions under the right eye, which may have led to sight loss in this eye,” Fleming said. “It is also important to note that … this lady being buried within St. Giles next to the altar of St. Anne indicates that she had high status, possibly within the tailors guild.”

In contrast, the 12th-century man was likely a peasant, which is why forensic artist Lucrezia Rodella, who is based in Italy, covered his head with a hood, “as it was a very common form of clothing during this time period,” Fleming said.

The man’s skull was missing its lower jaw, she added. “When something like that happens, it’s not possible to predict what the lower part of the face was like (mouth and jaw line), which is why [Rodella] decided to cover this part of the face with a beard,” Fleming said.

The man was likely between the ages of 35 and 40 when he died and stood about 5.6 feet (1.7 meters) tall.

To create the digital reconstructions, Fleming and Rodella took photos of the skulls and uploaded these images to Photoshop. The artists then looked for markers on the skulls that helped them measure tissue depth. “When these markers are added at various points of the skull, we get an idea of the face shape,” Fleming said. “We can observe the skull’s features and indicate how big the nose was, what kind of shape it was, the symmetry or asymmetry of the face, and so on.

“Once we have an idea of the face shape, we use a database of facial images,” Fleming continued. “This is used to select features that can be altered to fit the skull. Hair and eye color cannot be predicted unless the remains have been DNA tested, so we consider what might have been common coloring of people from that time period.”

The facial reconstructions were a collaboration with the City of Edinburgh Council and the Centre for Anatomy and Human Identification at the University of Dundee in Scotland. To see more of the digitally reconstructed faces from St. Giles Cathedral, go to Fleming’s personal webpage.

Sourse: www.livescience.com